Lobsters grow by molting. It's basically a process in which they struggle out of their old shells while simultaneously absorbing water which expands their body size. Marine scientists estimate that molting occurs about 25 times in the first five to seven years of a lobster's life. Once shedding their old shells, lobsters put on the feed bag in a big way.

Outdoors

D.E.C. Closes News Areas to Shellfishing

D.E.C. Closes News Areas to ShellfishingThere’s good and not-so-good news for commercial and recreational shellfishermen in the updated rules governing shellfish-season openings and closures in East Hampton Town waters.

On the Water: Fishing Legend Is Crowned

On the Water: Fishing Legend Is CrownedAt the culmination of the popular Montauk Mercury Grand Slam Fishing Tournament, Capt. Skip Rudolph, a third-generation fisherman who has made his living on the water for decades, will be celebrated as the Montauk Fishing Legend of the Year.

On the Wing: The Least Tern Is Most Interesting

On the Wing: The Least Tern Is Most InterestingLeast terns are properly named, they’re our smallest tern, and thin. They slice through the air, buoyant and bouncy, on clipped wingbeats, patrolling the waters below. They’re very vocal. Their call is high-pitched and squeaky, with a sharp grating quality. Learn it, and you will often hear them before you see them.

Glamping Returns to Cedar Point Park

Glamping Returns to Cedar Point ParkWhile it is less than a 15-minute drive from the hustle and bustle of East Hampton's Main Street in July, Cedar Point County Park in East Hampton's Northwest Woods feels a world away, which makes it both special and surprising. This year, Doug and Lee Biviano, who also operate concessions at the Fire Island National Seashore, have reopened the camp store and brought glamping back to the park.

On the Water: Farewell to Serena

On the Water: Farewell to Serena Serena Vegessi Schick, who died last fall, touched many in Montauk who work on the water, having spent years in her youth and early adulthood, as well as the final few months of her life, working the deck of the Bones netting or filleting fish, untying tangles, or just patiently helping youngsters catch the first fish of their lives.

Paddle Diva Is in a New, and Perfect, Place

Paddle Diva Is in a New, and Perfect, PlaceThe paddleboard and kayak rental and lesson business has a new home at the Three Mile Marina. "I feel so lucky. This is the perfect place," said Gina Bradley.

On the Water: Bunker in Short Supply

On the Water: Bunker in Short SupplySo far this year, Mother Nature has served up a curveball, as bunker showed up on schedule but dispersed rather quickly to parts unknown.

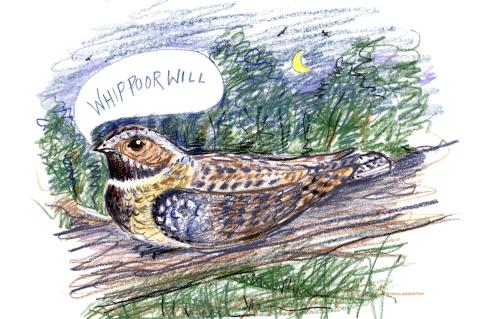

On the Wing: The Lonesome Whip-Poor-Will

On the Wing: The Lonesome Whip-Poor-WillThe scientific name of the whip-poor-will, Antrostomus vociferus, is spot-on. According to “Birds of America,” edited by T. Gilbert Pearson, “the first word . . . means ‘cave mouth’ and the second . . . ‘strong voice.’ ”

On the Water: Another Canceled Trip

On the Water: Another Canceled TripOnce again, the weather gods, despite sunny skies, spoiled our plans, as a gusty 30-knot breeze from the northwest would make fishing difficult and downright uncomfortable.

On the Water: An Age-Old Question

On the Water: An Age-Old QuestionOn the local fishing scene, the action has generally been good in many locales, and anglers of all ages have taken part.

On the Wing: The Endlessly Interesting Purple Martin

On the Wing: The Endlessly Interesting Purple MartinAs long ago as 1936, when T. Gilbert Pearson published “Birds of America,” purple martins were almost exclusively dependent on man-made housing. Here on the East End, they arrive in early April to the houses waiting for them and by Labor Day they're gone.

On the Water: Striped Bass Amass

On the Water: Striped Bass AmassWant to catch a striped bass? Then Montauk is clearly the place to be right now.

On the Water: Turbulence at the Gut

On the Water: Turbulence at the GutI decided to try a few quick drifts for striped bass in Plum Gut last week. The bass, according to reports, have been running in great quantities there.

On the Wing: The Best-Looking Songbird You've Never Seen

On the Wing: The Best-Looking Songbird You've Never SeenScarlet tanagers breed in forest interiors. Take a walk on the Sprig Tree Trail in Sag Harbor, or along the Round Pond Trail where they sing and breed. You'll also find them at the Grace Estate, Hither Woods, and Barcelona Neck. The trick is to find a large expansive stretch of woods and listen.

D.E.C. Offers Safety Tips for Outdoor Exploration

D.E.C. Offers Safety Tips for Outdoor ExplorationThe New York State Department of Environmental Conservation has issued a timely set of tips for people who plan to explore the great outdoors this summer.

On the Water: Mysterious Shrimp

On the Water: Mysterious ShrimpFor years I’ve noticed numerous symmetrical holes measuring about an inch in diameter in the sand near where I dock my boat in Sag Harbor Cove. Who created and resides in such dwellings?

On the Wing: The East End's Most Controversial Bird

On the Wing: The East End's Most Controversial BirdWhen beaches are closed because of nesting plovers, people get pretty riled up. The birds, which are endangered in the country and New York State, may seem to be prolific here, but in fact nest on only a handful of beaches on the East End. They're also site-specific, returning year after year to breed in the same spots.

On the Water: Pain in the Pump

On the Water: Pain in the PumpDense, foggy conditions over the weekend caused some anxiety for boaters and fishermen alike. The fishing was good in many locales, however, as the waters continue to warm up.

On the Water: Winds Blast Fishing Plans

On the Water: Winds Blast Fishing PlansThe northeasterly blow starting Friday was unfortunate, as the action on porgies, fluke, striped bass, weakfish, and even squid was on the upswing in many locations.

On the Wing: A Tempest of Towhees in a Teapot

On the Wing: A Tempest of Towhees in a TeapotThe eastern towhee breeds in Montauk, and if you go to Oyster Pond this weekend you can hear them calling and singing everywhere.

Beach Chair Birding Talk on Tuesday

Beach Chair Birding Talk on TuesdayChris Paparo, the manager of Stony Brook Southampton's Marine Science Center, is also birder, and on Tuesday at 5 he'll share some of his avian expertise at a virtual Accabonac Protection Committee forum titled "Birding From Your Beach Chair."

On the Water: Daffodils Wilt, Fish Arrive

On the Water: Daffodils Wilt, Fish ArriveA few weeks ago, Sebastian Gorgone, the gregarious and always welcoming proprietor of Mrs. Sam’s Bait and Tackle in East Hampton, explained to me that the local fishing season will get in high gear only once the daffodils begin to wilt. I had not heard of this local proverb before, and I wondered, was it true?

From Fashion to Fashioning Spaces

From Fashion to Fashioning SpacesWho better to understand the power of collaborations between brands than two women with backgrounds in the fashion industry, which seems to rely on the constant merging of brands? With 100 Design Style, Nikki Butler and Brigitte Branconnier created an interior design company that seems to strike the perfect balance between layout, light, color, tactile materials, and a connection to nature.

Let the Rain Fall

Let the Rain FallRain gardens offer an opportunity to work with nature to restore balance, using the contours of the land to capture water that flows to lower elevations. The plants’ roots absorb rainwater and nitrogen runoff, while the soil filters particulates before they end up in our waterways. And rain gardens are also a way to ameliorate the dramatic loss of 3 billion birds in North America over the past 50 years.

On the Wing: Think Like a Bird in Your Backyard

On the Wing: Think Like a Bird in Your BackyardTo make your backyard bird-friendly, you'll need to think like a bird when making landscaping decisions.

Remember, Leaf Blowers Are Regulated

Remember, Leaf Blowers Are RegulatedLike helicopters and jets, leaf blowers have long been the bane of many a South Fork resident’s existence, each one a portable spewer of pollutants and source of ear-splitting noise. But in towns and villages alike, enough residents got angry and organized, and governments listened. Today, the use of leaf blowers is restricted across the South Fork.

Save the Date

Save the DatePerhaps making up for two years of lost time, the spring and summer of 2022 will be filled with marvelous workshops, lectures, and benefits here on the South Fork.

Scott Bluedorn on Vermiculture

Scott Bluedorn on VermicultureScott Bluedorn, an artist and activist living in Sag Harbor, is also an aficionado of vermiculture — a contained composting system in which earthworms break down food scraps to quickly create a mineral-rich soil amendment.

Stop and Smell the Roses

Stop and Smell the RosesIn the Northeastern United States, at least, these blossoms — whether red, pink, peach, yellow, white, or some combination of all — are at peak perfection starting in late May through June. As you stroll about, drive around town, or even take the train, here are some South Fork spots where you can find this favorite flower.