Growing up on the rural North Fork surrounded by potato fields and water in the mid-1900s was idyllic for most of us. You could work as soon as you could walk, ride your bike anywhere day or night, play outside games like marbles, tag, hide-and-seek, giant steps, listen, look, taste, smell, and touch. You felt safe and secure.

Outdoors

The old expression was “he or she had sand,” meaning fortitude, and I think, seeing as how it was obviously a very old expression, “sand” referred to endurance or vitality, as in plenty of time remaining in the hourglass.

Let Nature Write the Script

Let Nature Write the ScriptWe agreed during a sail on Rob Rosen’s catamaran on Sunday evening — the soft wind quietly pulling the cat out of Montauk Harbor into Block Island Sound to watch the moon rise — that the bubble of exceptional weather had changed us. We had become accepting.

Nature Notes: On the Trail of the Monarch

Nature Notes: On the Trail of the MonarchTwo Wednesdays ago I was back at Crooked Pond south of Sag Harbor, this time with Victoria Bustamante and Arthur Goldberg, both of whom were new to the pond. The exposed flats, with their wonderful array of rare and opportunistic sedges, grasses, and flowers were still thriving. I say “opportunistic” because they only appear in odd droughty years when the pond level is way down.

Nature Notes: Sea Creates, Takes Away

Nature Notes: Sea Creates, Takes AwayA few weeks ago I was in the hamlet of North Sea with two California friends from my yippie days in Santa Barbara. We stopped at Conscience Point, where the first settlers to settle Southampton, from Lynn, Mass., came ashore in 1640.

Rats, Schoolies, Gorillas, Cows

Rats, Schoolies, Gorillas, Cows“Schoolie” bass were stacked up in one of the Gardiner’s Bay inlets the other morning toward the end of an outgoing tide. A Springs resident who shall remain nameless reported that he had decided on a whim to don a mask and snorkel and let the current take him along for a ride.

Getting Away From It All

Getting Away From It AllWe were alone on a secret beach, insulated from the crowds on that glorious summer day, and so the plane with its non sequiturious message — a crap duster seeding the clouds with yet another Hamptons pretension — made us feel like members of a cargo cult.

On Sunday I had the pleasure of leading a small group on a poke-and-look nature walk along the Long Pond Greenbelt trails south of Sag Harbor, sponsored by the Friends of the Long Pond Greenbelt. “Poke-and-look” because we shuffled along slowly, conversing, asking questions, answering them, and taking in the wonderful flora on either side of the trail as we wended our way towards Crooked Pond.

Doesn’t Get Any Better

Doesn’t Get Any BetterThe subject is sheer delight. I tied up to the town pumpout station next to the Coast Guard station on Star Island in Montauk on Monday, late morning. While I offloaded what needed to be gone and topped off my water supply, what looked to be a family — a man, a child about 9, and a woman — were fishing off the end of the town dock.

Nature Notes: What’s on the Menu?

Nature Notes: What’s on the Menu?I live on a fifth of an acre but there is still enough room to accommodate a visiting deer or two. I rarely see them, but I see their discrete fecal piles here and there, a couple of new ones each week.

It’s All About the Flow

It’s All About the FlowFlow. It’s what we want, not hangs. I have a friend who moved way down south to a dirt-road town called Pavones. It’s located on the southeast side of the Sweet Gulf, Golfo Dulce, not far from the Panamanian border, where some of the finest waves in the world peel along the Costa Rican coastline.

Nature Notes: Dog Days’ Night Music

Nature Notes: Dog Days’ Night MusicIt’s been hot as Hades and unrelentingly humid. In other words, the air is almost filled to capacity with moisture, but not the kind that produces rain. Plants are wilting and songbirds are trying to stay cool by lying low and not singing.

A Shiver and a Bloat

A Shiver and a BloatA shiver of sand tiger sharks approached the beach from the south in downtown Montauk and a large body of bluefish that were hunting schools of smaller prey concentrated between the sharks and a bloat of boogie boarders.

If you’re a child, tween, or teen, summer is a time for work and play away from the confines of the classroom. I wouldn’t trade my boyhood and its summer for all the gold in Captain Kidd’s chest. Growing up in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s on the North Fork was all that a lad could wish for.

Fishing Legend of the Year

Fishing Legend of the YearCapt. Mike Vegessi of the Lazybones party boat out of Montauk was named Fishing Legend of the Year at the Montauk Mercury Grand Slam fishing competition held on Saturday and Sunday from Uihlein’s Marina.

You may have noticed that most of the songbirds have stopped singing and are either preparing to nest again or, more likely, just help their fledglings along while simultaneously nudging them away. Young-of-the-year ospreys have either already fledged or are standing in their nests flapping their wings in earnest as they anticipate the moment of departure.

Three More Sharks to Follow

Three More Sharks to FollowSendero Luminoso, the organization of Maoist revolutionaries of Peru, always comes to mind when I’m offshore on a boat that’s shark fishing. This only makes sense because of the dream state one drifts into while, well, drifting, as the crew spills ground fish and fish chunks overboard to create un sendero luminoso, a shining path that wanders toward the horizon as time passes, a route for hungry sharks to follow until they meet the boat’s baited hooks.

Climate Change Alters Nature's Song

Climate Change Alters Nature's SongHigh mercury levels in East Coast marshes could wipe out some bird species, according to researchers.

Montauk’s Money Tide

Montauk’s Money TideMy son-in-law stood over the stove Monday evening stirring diced vegetables that would go into bass cakes along with a medley of spices, an egg as binder, and crackers crumbled by hand. The 40-pound striped bass providing the substance of the cakes was speared on Saturday by the same man stirring the veggies.

Nature Notes: Gypsy Moths 2016

Nature Notes: Gypsy Moths 2016Just about every school kid in the East knows about gypsy moths. If you asked them what one looks like, though, they’d be hard pressed to describe it.

Nature Notes: More or Less?

Nature Notes: More or Less?Well here we are well into summer and the birds have successfully fledged many of their young. Will they go for a second brood? Piping plovers are one of those species that tries and tries again if it fails the first time around.

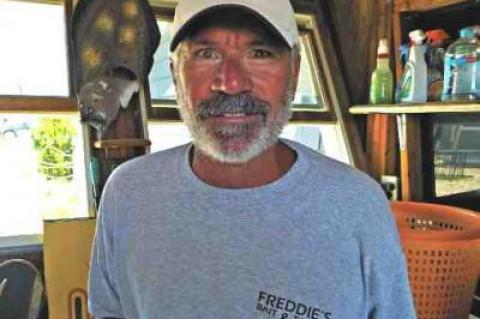

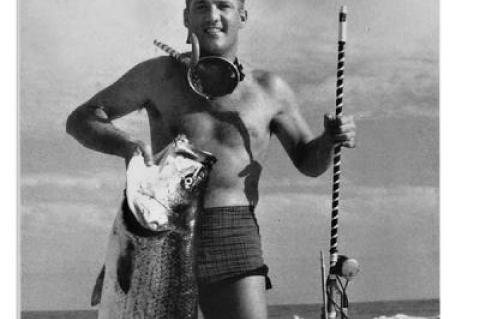

Part Man, Part Fish

Part Man, Part FishGeorge Knoblach turns 90 today. Like many a Montauk resident, George “discovered” this place during his family’s summer camping trips to Hither Hills State Park — only much earlier than most.

Nature Notes: From Bog to Forest

Nature Notes: From Bog to ForestThe inch or so of rain we had on Saturday and Sunday morning really greened up the open spaces. It was readily apparent on driving around the outback areas of Southampton and East Hampton on Monday. The vegetation had been getting thirsty. Its thirst was thusly quenched.

An Eye on the Shark’s Eye

An Eye on the Shark’s EyeThis season’s no-kill shark fishing tournament is named the Carl Darenberg Memorial Shark’s Eye Tournament after the late owner of the Montauk Marine Basin who broke with precedent by maintaining the Marine Basin’s exciting tradition of shark tournaments while sparing the lives of sharks.

Monday night was delicious. It was quiet and as late as 9 objects big and small could still be discerned with the naked eye without the addition of artificial lighting. It was a perfect night to go out and scour the woods and fields for whippoorwills, without leaving the driving seat of my vehicle. So that’s what I did.

We Are Predators and Prey

We Are Predators and PreyI had lunch at the Inlet Seafood restaurant in Montauk on Monday afternoon. There were five of us, one of whom pulled out his smartphone as we waited with delicious anticipation for sushi, mussels, and broiled mahi sandwiches.

Change of Command at Coast Guard Station Montauk

Change of Command at Coast Guard Station MontaukSenior Chief Petty Officer Jason Walter handed the helm to incoming Senior Chief Petty Officer Eric Best. He then retired after 21 years of service to his country, and, by all accounts, extraordinary service to the Montauk and East Hampton communities during his last assignment.

Nature Notes: A Lushness Value of Nine

Nature Notes: A Lushness Value of NineIt rained and winded Monday, not a good day for taking pictures of plants and flowers. But it was okay. We needed the rain and I hope it won’t be the end of it during the coming summer. It was okay because I had finished doing my annual end-of-spring gypsy moth and groundcover monitoring for 2015.

Nature Notes: Want Butterflies? Go Native

Nature Notes: Want Butterflies? Go NativeIt’s the peak of the breeding season for almost every bird, mammal, reptile, amphibian, and fish, not to mention shellfish and crustaceans. It’s also the middle of the landscaping and gardening season, when lots are being cleared, new houses constructed, lawns planted with exotic shrubs, trees, and forms.

Under the Full Moon

Under the Full MoonThis time of year the very thought of the full moon illuminates the imaginations of fishermen of all stripes, whether they lower clam bait, live eels, or cast lures of many disguises in hopes of hooking Morone saxitilis, striped bass.