A Little Bit in Love

A Little Bit in Love

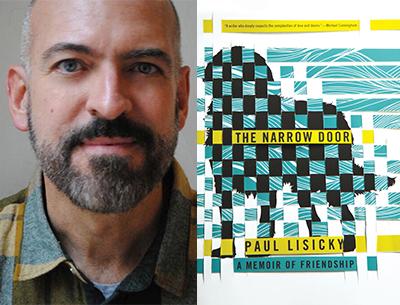

“The Narrow Door”

Paul Lisicky

Graywolf Press, $16

“The Narrow Door: A Memoir of Friendship” is a narrative of comradeship and grief, of love and woe. Paul Lisicky offers an honest and sometimes raw account of his relationships with two major players in his life, and outlines the intersection of loss that marked his experience. The work takes up Mr. Lisicky’s friendship with the writer Denise Gess — a long and intimate friendship of 30 years. He describes her vitality, her magnetic quality, her passion for writing and talking about writing.

About their relationship, he writes, “It doesn’t matter anymore that she’s straight and I’m not. See how we’ve been a little bit in love all this time, and not able to say it? But that’s the story of any friendship that lasts this long.”

This relationship is remembered alongside the dissolution of Mr. Lisicky’s marriage to M, who is initialed thus but not named, and described as a well-known poet. Eventually, Mr. Lisicky and M break up in the aftermath and shadow of Ms. Gess’s death. Throughout, there’s a powerful sense of grappling present in the writing that speaks of working through the shape and texture and dimensions of a Difficult Time.

The book is structured through a syncopated chronological flow of scenes and description. Passages within named chapters are labeled by year. The bulk of the chronology is the span from the mid-1980s, when Mr. Lisicky’s friendship with Ms. Gess began, through to her death in 2009 and the end of his relationship with M in 2010. However, the years do not proceed in chronological order. Instead, they switch and repeat in an unpredictable pattern.

The structure of the book as a rearranged and re-emphasized chronology feels musical and even at times magically attuned to the rhythms of life. The mystery of friendship, the complexity of love, the textured fabric of loss. These ideas are explored and underscored as they resurface over the course of the book.

Through warmth, humor, and even through the striving of Mr. Lisicky’s narrative voice, the reader becomes allied with him, starts to feel friendship-prone, protective of him, even. For example: Two-thirds of the way through the book, Mr. Lisicky’s marriage is clearly on the rocks and M has not only taken a boyfriend on the side but effected an arrangement whereby he spends one night a week with said boyfriend while Mr. Lisicky agrees to stay elsewhere (the house in Springs or the apartment in New York, depending). What? As Mr. Lisicky’s new reader-friend, I am not okay with that.

Anyone who cannot imagine laughing around a dinner table with Paul Lisicky would probably not be much fun, dinner party-wise or otherwise. Many would want to be in his orbit. And Mr. Lisicky is no stranger to the seduction of a sense of belonging. Indeed, an in-club vibe does emerge in the book, a sense of posturing for position within the contemporary writing scene, with the danger of name-dropping (without some of the names) present to an extent.

Yet the pitfalls of just those vanities come into play in Mr. Lisicky’s analysis of his friendship with Ms. Gess, as well — he discusses the complex sense of competition between them as writers, the barrier it produced. He touches on the way one’s life path is connected to success, and sometimes proximity to success (examined through Ms. Gess’s affair with “Famous Writer” — it will be easy for many readers to guess the identity of this person — and Mr. Lisicky’s relationship with M, a.k.a. the well-known poet, his name also surely less than a Google away).

Mr. Lisicky’s work has a place in the growing constellation of contemporary memoirs of friendship by writers about fellow writers. (There are more than several worth considering, among them “Truth & Beauty: A Friendship” by Ann Patchett, on her friendship with Lucy Grealy, and “Let’s Take the Long Way Home” by Gail Caldwell, on her friendship with Caroline Knapp.) His work falls in the searching/striving zone, and will find favor with a variety of readers.

This dual tale of friendship and marriage showcases the scenic quality of memory. It fluffs the material, frames it, providing display cases in which theme and memory may pause to be considered. The book serves as a model of the process of coming to understanding through remembering. Near the end, Mr. Lisicky poses a question against the backdrop of the memorial reading he organized for Ms. Gess at City College:

“What is it like to know a single human in time? That is the question that inevitably organizes our listening. There’s nothing more absorbing than thinking about all these changes over the years. It’s not that the progression is linear. It’s just that her obsessions — the twin poles of shame and grace — move like a spiral, rotating around a core.”

Remembering is not a linear process, but still exists on a timeline. Mr. Lisicky has arranged his memories. He invites us to share his understandings.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Art of Quitting.” She lives in East Hampton.

Paul Lisicky’s four previous books include “The Burning House,” a novel. He teaches in the M.F.A. program at Rutgers University’s Camden campus.