Storm Warning

Storm Warning

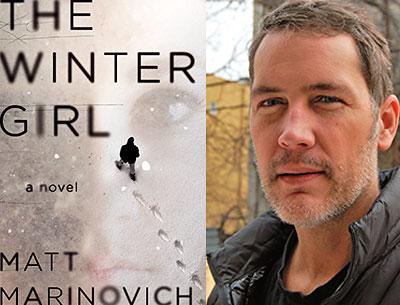

“The Winter Girl”

Matt Marinovich

Doubleday, $24.95

“The Winter Girl” is Matt Marinovich’s second novel. I suppose you could call it a mystery, though it has an odd quality that sets it apart from standard murder mysteries. Set in Shinnecock Hills in the off-season, “The Winter Girl” is cold, dark, bleak, and wintry. The book, like an impending winter storm, is filled with menace and the threat of destruction.

It is narrated by Scott, who with the benefit of hindsight tells his story from some time in the future. Scott and his wife, Elise, live in Brooklyn but are staying at her father’s house in Shinnecock Hills so that she can visit him at Southampton Hospital. Her father, Victor, has metastatic colon cancer. Elise’s younger brother, Ryder, can’t help because he is in jail in Ohio, doing a five-year stretch for burglary and distribution of a controlled substance. When Ryder calls collect from prison, Elise takes the calls secretively in a room away from Scott’s hearing.

Scott and Elise are an unhappy couple, both individually and together. “I’d wasted ten years of my life,” Scott tells us, “pretending to be a photographer.”

“At night, Elise and I mostly watched television and avoided talking about how long it was taking her father to die. By early December, it was getting dark pretty early. By then, we had a routine down. I’d have dinner ready by the time I heard the wheels of our car on the short gravel driveway. . . . Once she gripped the steering wheel and pulled at it, as if she were going to tear it off. Then I saw her wiping the tears away . . . her mouth still gaping with grief. If you’re wondering why I didn’t run out there and comfort her, I don’t have an exact answer. One of the reasons is that it had been going on for almost a year.”

Because it is winter, and because it is the Hamptons, the houses around Victor’s home are empty. But the one right next door has lights on a timer. Scott, having too much time on his hands, finds this fascinating and spends a lot of time looking at the house through Victor’s binoculars. The lights in the seemingly empty house go on and off at set times every day. Every night at precisely 11 o’clock the lights in the bedroom click off. For some reason this unnerves Scott.

“Besides my steadily growing affair with the house next door, there were other disturbing developments that week in December.” Victor begins calling from the hospital, leaving rageful messages on his home machine. “You son of a bitch,” he says. “Pick up. I know you’re there.” He leaves many angry messages. “How does she let you touch her? You’re a piece of shit.” He threatens to drown Scott in the bay with his own two hands.

Elise, when she comes home from the hospital, blames it on the illness and the morphine. But Scott “always suspected that she had an uncomfortable secret regarding her father.” That night, she tells him some of it. We don’t get to know — at that point — just what Victor did to her, but, “It’s sick and it’s sad and a father who does that to his own child deserves a far worse death than being drowned in a bay.”

It is a tricky thing to review a book like “The Winter Girl” if you don’t wish to give away too much of the who-done-it-who-is-gonna-do-it. It would deeply spoil the read to reveal major plot points in a story such as this. I can comfortably say, however, that Mr. Marinovich believes, as Chekhov famously asserted, that if you don’t intend to use the gun at some point in your story, then don’t show it: “. . . deeper in his closet, an old shotgun zipped up in a beige bag. . . . I preferred my Nikon.”

Suffice it to say that “The Winter Girl” has a dark and nebulously dangerous pall hanging over it. And the gun, as Chekhov would approve, gets used.

There are several areas of tension. Scott and Elise’s marriage is clearly hanging on by the slenderest of threads. I vacillated between wondering if they intend to divorce or to murder each other. It turns out that Victor is quite rich, but it is questionable whether he will leave any of his fortune to his daughter. One cannot help but wonder would Scott or Elise want to kill the other for possession of this fortune? Do they want to kill Victor for the money?

Another tension is the house next door. It is spooky in its deserted and seemingly abandoned condition. But it is a powerful lure for Scott, who is bored and lonely and becomes increasingly brazen about exploring it. Finally he finds an open door and trespasses.

Scott tells us, “The worst decisions never let you go. They come circling back, even on the best days, to find you.” That night, he and Elise get drunk, and he takes her over to explore the cold and empty house. He says, “I had this feeling that as long as we snuck around this house, we might stop finding ways out of the marriage. You need each other more when you have no idea what’s going to happen next.” They end up screwing in one of the cold bedrooms.

Afterward, Scott starts to straighten up and pulls the comforter off the bed they have just finished on, only to reveal that the sheets beneath are stiff with dried blood. A lot of blood. Scott assumes someone has been murdered on the bed. Elise vomits when she sees the gore. They think about calling the police, but, out of what seemed to me a misguided fear of explaining their own trespasses to the police, decide not to. Instead, later, Scott goes over to the house with a bucket of soapy water to clean up any fingerprints and DNA traces they may have left.

The house turns out to be occupied by an enigmatic and very strange young woman named Carmelita. Her relationship to the house, and as eventually turns out her connection to Victor, is unclear at first. Victor sends small amounts of cash to her, a few hundred here and there through Scott, and Scott does not know why. She knows a great deal about not only Victor, but also about Elise. Carmelita had some kind of sadomasochistic sexual thing going with Victor. Scott is “sickened by the precise blue and dull orange bite marks around her small breasts, as if some insane suckling child had tried to tear away her dark nipples.”

Mr. Marinovich’s novel is a dark and gloomy and threatening read. When the ominous winter storm finally breaks, the story builds to a crescendo of murder and betrayal and brutal sadism. “The Winter Girl” is certainly no light summer read.

Michael Z. Jody, a regular book reviewer for The Star, is a psychoanalyst and couples counselor with a practice in New York City and Amagansett.

Matt Marinovich has been an editor at Interview and People, among other magazines. He lives in Brooklyn.