He’s No Jack Reacher

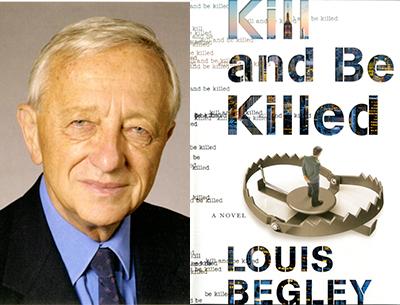

“Kill and Be Killed”

Louis Begley

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, $25.95

Having been assigned Louis Begley’s new novel, “Kill and Be Killed,” I have, I confess, committed the first sin of book reviewers. I did not finish the novel. I apologize, but I just could not. If Mr. Begley and his publishers deign to read this modest review, they will undoubtedly use this admission to disregard any momentary sting my words may cause them, then chalk the whole thing up to snark. For others who have no financial or filial connection to this book, however, let me assure you that this is a novel that you too will be unlikely to finish, and may have a hard time keeping out of the fireplace.

For the record, I have read two previous books of Mr. Begley’s, and enjoyed them both in varying degrees. “The Tremendous World I Have Inside My Head” is an insightful, if slender, biographical essay on Franz Kafka, while “Wartime Lies” is among the indispensable Holocaust novels. The latter was also nominated for a National Book Award.

“Kill and Be Killed,” meantime, seems dropped from another planet.

It is a cynical book. It is a hastily written book. It is, at times, an utterly illogical and stupid book. Worse, it is a book that if you shined a black light on it to reveal the invisible ink, you would see dollar signs where you had thought there were words.

“Kill and Be Killed” is the second in a series that began with “Killer, Come Hither,” and clearly the strategy here is to zoom in on the wings of Lee Child’s Jack Reacher series and hit the commercial thriller genre up like an A.T.M. Mr. Begley even appropriates Mr. Child’s hero, Jack Reacher, who in these novels is called Jack Dana. Dana, too, is a military veteran. But where Reacher is a credible character of harsh logic and monastic habits that allow him to move in stealthy pursuit of his target, Dana is an illogical mix of cold-blooded killer and dedicated sensualist (not to mention a novelist, for reasons that will escape the reader) who never lets murder or injustice get in the way of an afternoon at the museum or a good meal.

First, the writing. One of the hopes with reading a genre book by a world-class author is that you will encounter a higher grade of prose than the average thriller offers, some golden nuggets to savor among the clichés. John Banville’s Quirke series, for example, is beautifully written, as are the mystery novels of Jim Harrison. Though “Kill and Be Killed” has its moments, the writing in general seems harried, and Mr. Begley is somehow content to include dialogue such as “I’ll hunt you down like the varmint you are.” It’s a line that will remind readers more of Yosemite Sam than good noir.

And then there is the matter of basic logic, which is in woefully short supply. It begins in Venice, where Jack is holed up working on a new novel and suffering over a woman named Kerry who has recently left him. Just as Jack makes the decision to return home and try to win her back, he suddenly learns that Kerry has died (officially of an overdose, though he suspects murder). Naturally Jack hops the first plane back to New York to comfort friends and family, help make funeral arrangements, and begin his own investigation. Right? Actually no. He immediately cancels his flight while offering this explanation:

“Whatever else I may have been telling myself, the real reason I wanted to return was to win back my poor Kerry. Now there’s no point. I won’t stay here forever, but I can work here pretty well. The time to return will come, but not now.”

In other words, If she’s going to die on me, then screw it, I’ll get back to my novel. In fact, Jack hits the desk the very next day and produces, we are told, “twice my daily quota.” Nothing like the death of an old flame to set the creative juices flowing.

So Jack remains in Venice, where he grieves Kerry’s death in the eternal way of mourners everywhere: by checking out the paintings of Titian, eating good Venetian food, and getting in a workout with his trainer, Fabrizio.

There is also the thoroughly laughable scene where the hero is confronted by an assassin, presumably in a pre-emptive move by the novel’s evil billionaire, Abner Brown. Logic tells you that when a wealthy man like this wants to off somebody, you can expect a pretty high level of competence and discretion — they can afford it, after all — and so the call goes out to a world-class sniper, or a master engineer to rig a fishy car crash. If it’s Vladimir Putin, maybe some plutonium in your puttanesca.

Not Brown, however. He sends an assassin whose weapon of choice is, of all things, a crossbow. Not only this, the killer’s aim is a little askew (jet lag, maybe?), and he expends no less than 10 arrows on Jack, none of which come close. Mercifully, it seems, the hero guts him like a pig: “I sliced his belly open,” explains this gourmand/novelist/Marine. “The guts spilled out . . . he continued to writhe and howl. It got on my nerves . . . I slit his throat.” Soon after, for identification’s sake, Jack cuts off the killer’s finger and stuffs it in his pocket.

Gruesome as this scene is, it’s still early in the novel; later on we get scenes of cruelty and gore that would make Quentin Tarantino blush. I’m no prude, but it’s a little disappointing to watch an author who has written so intimately about the Holocaust trafficking in violence so casual and gratuitous. You may wonder where this sensibility is coming from, but then you can probably guess. Did the author suddenly, after a dozen books, spawn a sadistic imagination? Or is it because he thinks this is what you want, cynically pandering to the bloodlust he believes you carry in your heart, as if all thriller readers were barbarous rubes.

On and on it goes: the implausibility, the great meals, the gleeful cruelty. I finally checked out around page 150, which of course raises the question: Was I remiss in my duties by not finishing this novel? Is a reviewer obliged to read to the end of a book no matter how shabbily he or she is being treated? Have I mentioned how illogical it is that Jack Dana, who is in his early 30s and has spent the better part of his life as an active Marine, is conversant on subjects as diverse as St. Augustine, Philip Roth, Edward St. Aubyn, and Italian Renaissance art, not to mention fine wine and international cuisine? (The 30-year-olds I know have no idea who the Beatles were.) Or that when a package arrives at Jack’s apartment he suspects is a bomb, he calls neither the F.B.I. nor even local police, but instead puts the package in his library for later inspection? Or that the very day after his maid is brutally assaulted on the streets of Manhattan as a provocation/warning from his nemesis, he decides to go on an early-morning jog through the most remote barrens of Central Park, only to be confronted by one of Abner Brown’s thugs?

Some novels you can’t put down; others seem to defy you to finish them.

Why so hard on Louis Begley’s “Kill and Be Killed”? Because it is a corrupt novel written by an important author trying to cash in on a genre for which he has no instinct or respect. And because I know he can take it, since it is inconceivable that the author could have any emotional attachment to a book where everything has been so blatantly, if clumsily, appropriated. And finally, because Mr. Begley has apparently hit a point in his career where he thinks it’s okay to make a little cheap money, that he has done good work and deserves this, and because I suspect he wants to go back to Venice for the Barolo grappa and the sumptuous Titians and wants you to pay for it.

Don’t let him.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.

Louis Begley lives in Manhattan and Sagaponack.