Jester With a Dark Streak

Jester With a Dark Streak

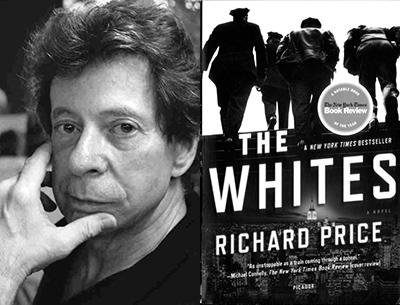

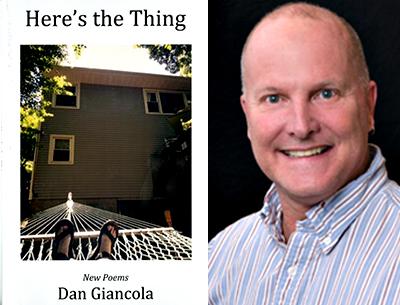

“Here’s the Thing”

Dan Giancola

Street Press, $15

The persona of Dan Giancola’s “Here’s the Thing” has been around the block and then some.

The book’s title establishes the hip persona whose contemporary clichés are a cover-up for dealing with a dark world. Whether speaking through the mind of “Mister Sister,” boldly introducing a layer of ambiguity in its gender fluidity, or in his ironic, jaundiced voice, the view is bleak. Mr. Giancola, who sees the world as fundamentally disordered, addresses its mundanity in a surreal everyday as “sushi rolls off the table, putting waiters in a snit,” celebrates ways “to spend the last dollar,” and boasts, “My pad don’t look too slummy.”

Underneath this comic braggadocio lies the true subject of “Here’s the Thing”: illness and death. References to both abound.

Mr. Giancola expresses our inevitable confrontation with death most explicitly in his long poem sequence “An Ordered Tour Through the Chaotic Mind of Mister Sister,” which is the heart of the book:

Mister Sister’s terminal (ain’t we all?)

but acclimating nicely (Thank You

very much) to the idea of dying. Stall

all you want but your day’s coming too.

His puns, besides showing off, mitigate the pain of our mortality. The overriding tone of the poems is that of the court jester who, underneath his jests, conveys the truth that we will die.

Mr. Giancola is in fact a shameless punster with references to poets such as Wallace Stevens: “the Supreme Friction enjoys / its own dissolution.” He tempers his vaudeville humor with dictums that stand alone as stark truths, as in these lines from “Sunken Drive”: “We have to work at happiness”; “Age is the change we feel most keenly / its inevitability & our mustering a poor fight,” and this with its wonderful simile of passage: “We all know the years pass like boxcars.”

“An Ordered Tour Through the Chaotic Mind of Mister Sister” also provides a commentary on the art of poetry, the poet’s love and frustration. He writes of the Muse: “Because she provides nothing but doubt / doggerel and despair, Mister Sister broke / it off with the Muse, throwing her out / on her ass where she lingered to smoke / saying, you need more ambition.” Even the Muse ages, no longer providing fresh images and bringing “the usual dreck — a list / poem, a rhapsodic ode that lies / about love no better than a Hallmark / card, an angry political sonnet / elegies for people gone yet / not forgotten. . . .”

The Muse tells Mister Sister, “I’m gonna make you wish you never heard of rhyme. / Remember, I made Miss Moore dislike it!” The reference to Marianne Moore, another allusion to modernist poets, tells us how much Mr. Giancola is invested in poetry and its tradition even as his poetics rebel against them. For example, unconventionally he uses the letters of the alphabet from A to Z rather than numbers for each of the sequence’s sections.

Mr. Giancola’s persistent use of rhyme contributes to the book’s jauntiness while serving as another defense against despair. Frequent enjambment also serves this purpose while pronouncing at the same time how clever the speaker is in spite of the odds against virtuosity holding back the dark. His use of the ampersand provides an echo of Black Mountain and Beat poets to break through traditional poetry’s conventions as well as life’s conventionality.

In between his joking and his tough guy stance, Mr. Giancola reveals poignant feelings. For example, “Nothing’s lonelier than an unfinished poem”; and from the poem “Glib Yak”:

You can rob & tax me, jail & assail

me, sicken & doubt me, withhold my ale

but don’t tell me how to feel.

The last poem, “Loopy,” sums up the philosophic attitude of “Here’s the Thing” as the poet dispenses advice to the reader in an old-fashioned homily juxtaposed against his idiosyncratic voice:

Can’t you see it’s true?

You know what I mean.

No world we’re part of wants us

so it’s best to make our own.

Life’s re-runs leave you loopy.

Karma goes around like flu.

Dignity is all that’s left.

Faking happiness will kill you.

Death warrants arrive postpaid.

Best to keep small beneath the sky.

You’re gone now, buddy

& no asking why.

As Bette Davis famously said in “All About Eve,” “Fasten your seat belts; it’s going to be a bumpy night.” So, too, the reader of Dan Giancola’s “Here’s the Thing” will experience an uncomfortable journey through diverse poetic strategies: street talk, contemporary clichés, philosophizing, in-your-face rhymes, and puns. And well worth it.

Carole Stone’s new collection of poems is titled “Late.” A professor emerita of English at Montclair State University, she lives part time in Springs.

Dan Giancola teaches English at Suffolk Community College and lives in Mastic. His collections of poems include “Songs From the Army of Working Stiffs” and “Powder and Echo: Poems About the American Revolutionary War on Long Island.”