Light for the Shadows

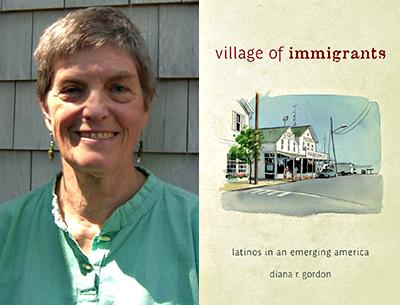

“Village of Immigrants”

Diana R. Gordon

Rutgers University Press, $27.95

One-third of the full-time residents of Greenport are Latino, the first of many facts to surprise me in this lively and valuable contribution to understanding the Village of Greenport today. In her book “Village of Immigrants: Latinos in an Emerging America,” Diana R. Gordon, a retired academic, has drawn a portrait of the village that is thorough but not pedantic, granular at times, sweeping at others, and, at its core, a personal story: Ms. Gordon lives in Greenport, it is her hometown, and she wants its Latinos to stay and prosper.

Between 1880 and 1910 more than 17 million foreigners arrived in the United States, admitted as immigrants and expecting to be employed as manual laborers. Its unique charms notwithstanding, Greenport exemplifies a nationwide pattern of immigrants settling into rural areas, seemingly indifferent to the pull of large coastal cities. Framing Greenport as “Absorbing Immigrants Since 1840,” as one section of the book is titled, Ms. Gordon recounts its history of immigration and settlement, tracing its rise and fall — “Boom, Bust, and Back Again” — until the present day.

The name “Greenport” was established in 1831; however, the hamlets of Southold Town and the Village of Greenport remained isolated until 1844, when the first train of the Long Island Rail Road arrived in Greenport from New York City. Through the centuries, the people of Greenport were robustly employed in whaling, shipbuilding, fishing, menhaden and oyster processing, and brickmaking; with the advent of the railroad came the summer people and, for them, the hotels and restaurants their lifestyles demanded. The good years were followed by the calamity of the 1938 Hurricane and a severe postwar downturn. The rich fled, leaving workers unemployed, vacant housing, and a heroin epidemic.

The picturesque “leafy calm” that Greenport offers its visitors in no way betrays its now-invisible history of economic and demographic collapse that began after World War II and continued into the 1950s and ’60s, ending when enlightened mayors and dedicated citizens began implementing a plan to clean up its deterioration and revive its downtown, with financial support from government and private funds.

Ms. Gordon aptly describes Greenport as “a magnet” — for retirees, second-home owners from New York City, tourists, and, starting in 1990, Latinos from Mexico, Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras), and South America (Ecuador and Colombia), rapidly rising, as reported by the 2010 census, to one-third of the village’s full-time population.

Published at a propitious time, “Village of Immigrants” puts into stark and repulsive relief the cruel language in which the 2016 election debate is taking place in this country, in particular the unbridled bigotry with which presidential candidates characterize immigrants and promise immigration policies. In contrast, Ms. Gordon sets today’s Hispanic population, a term she uses interchangeably with Latinos, in a historical context of waves of immigration that have shaped Greenport.

Each chapter sets out one of the many challenges awaiting an immigrant individual or family, documented or undocumented: school, language, housing, health care (“Cobbled Care”), licenses and lawyers, work, feeling American. Augmented with detailed profiles of real (but disguised for confidentiality) individuals — Edgar, Sofia, Javier, Jorge, Ricardo, Patty, their travails and their triumphs — these chapters build a rich picture of immigrants that is both personal and individual, but through their layers the chapters are transformed into portraits of families and ethnic groups. (To watch a televised G.O.P. debate immediately after reading Ms. Gordon’s work is to wonder how the debaters’ combative promises and threats are experienced by those “living in the shadows.”)

The shortsighted emphasis on immigrants as “takers” obscures the lesson that Greenport is learning: Immigrants are also consumers who contribute to the gross domestic product of the village. Increasingly, they are homeowners and owners of small businesses, contributing to the village tax base. Although some complain that immigrant children are a tax burden on the schools, Greenport is beginning to see that without them its aging population could well leave the schools moribund.

Perhaps the generosity with which she shares the respect, admiration, and affection she feels for the people she writes about is Ms. Gordon’s most important contribution in “Village of Immigrants.” Their ambition and work ethic, she writes, “are good for Greenport and good for the country. That the immigration system doesn’t reward them is a national shame.”

She credits village residents and officials, including law enforcement, with special mention of former Mayor David Kapell and Sister Margaret Smyth, for making allowance for the “precarious” nature of immigrants’ lives and points out that most illegal immigrants start life in America having broken the law and in debt (to the coyotes who trafficked them over the border). Although the author cannot officially bring Greenport’s immigrants out of their shadows, she has taken us into their shadows, to experience what it means to live a life sin papeles.

Without its immigrant workers Greenport would not be the thriving small town it is today. Ms. Gordon fears that unless its environment becomes more hospitable for its lower-wage worker population, Greenport could enter a period of stasis, regressing into a two-level demographic of wealthy second-home owners and poorer permanent workers to service those homeowners. Such reduced heterogeneity would rob Greenport of its multicultural charm and, more significantly, prevent the emergence of a vibrant middle class.

Central to this undesirable outcome is an affordable housing market discussed in the chapter “Housing or Houses?” The high cost and insufficient availability of rental housing puts a roadblock on the path to fuller participation in the economy.

Greenport — and the Town of Southold — would do well to pay greater attention to the policy implications in Ms. Gordon’s book. An unapologetic champion of Greenport, she writes about the village’s provision of health care through HRHCare, an accountable care organization: “In its small way, Greenport has been ahead of the transformative care curve, at least for its immigrants and low-income residents.”

And then she goes further, asking in the last chapter if it is “A Small-Town Model?” Compared to other small towns (Perry, Iowa; Independence, Ore., among others), Greenport does offer multifamily houses for low-income tenants, its schools are not closing, its economy is based on small businesses, and blatant anti-immigrant hostility is unusual. “And how,” she asks, “can Greenport, initially successful at absorbing today’s immigrants, nourish that accomplishment in ways that foster true integration?”

To make policy or predictive claims is to go beyond Ms. Gordon’s intention; nevertheless, she urges her hometown’s politicians and planners to consider her observations and to delve further into the successes and failures of immigrant absorption experienced by other small towns in America. Without close strategic attention being paid to planning for economic development, housing, seasonal variations, and many other variables that affect both immigrant and native populations, she warns, future revitalization is anything but assured.

Hazel Kahan is a writer and the host of two interview programs on WPKN Radio. She lives in Mattituck.