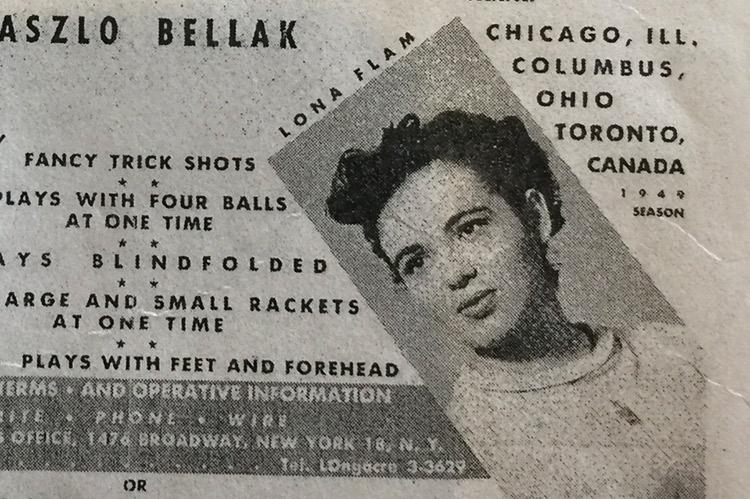

Lona Rubenstein of Amagansett may be better known in recent years as a world-class poker player, but long before she took up that game, she was a champion in table tennis, competing nationally and internationally.

She began playing — and winning — as a child in the 1940s and continued to win international table tennis matches as the mother of three children into the 1960s.

“I grew up in Washington Heights, across the street from the George Washington Bridge. I was maybe 10 when I began playing, every Saturday, with Johnny Gwon, whose family had a Chinese laundry on 181st Street at Fort Tryon Park, where they had stone tables. You brought your own net.”

“The Gwons . . . also had a restaurant in the theater district. I ironed sheets at their laundry before I burnt one. Washington Heights was a very strange place. There were Spaniards, a lot of Greek Orthodox, Armenians . . . the Irish lived on Amsterdam Avenue — everyone thought they were ruffians. It seemed that all of Europe dumped its minorities in Washington Heights. Being Jewish wasn’t a big deal.”

Rubenstein’s home away from home then was the YM-YWHA, where there were “some of the best table tennis players in the country.” The women’s national champion, who was 18 at the time, played there, as did the second and fifth-ranked male juniors. “I was the youngest at 12,” she said.

Her father, David Flam, was a pro tennis player when he was 16 and gave lessons in Central Park. He “was what they called in those days a publicity man — a press agent. He handled some big people, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., Charlie Chaplin, Ginger Rogers . . . he discovered her . . . Gene Kelly. . . . He used to go out for the paper and not turn up again for two years. He gambled. He was very smart, nothing impressed him. He found everyone interesting. He would rather talk with the shoeshine guy than with actors and actresses who were full of themselves. There was no class, no race, no religious consciousness in my upbringing. He was a very good guy . . . but he wasn’t around much.” Consequently, her mother “had to work, and my grandmother, who came to this country at the age of 14 from Austria-Hungary, really raised me.” She was “a doer and a giver.”

Her father “was good at racket sports. . . . But he was defensive, I was aggressive. They said I had one of the best forehand drives in the world. So the YM-YWHA players began bringing me downtown when I was 12 to Lawrence’s table tennis courts at 54th and Broadway, where there were Ping-Pong tables on the second and third floors. Theater people would come up, athletes like Frank Gifford would come up to waste some time or watch. People loved watching me play — I was second in the juniors that year, when I was 12.”

“I hit as hard as anyone in the game, but it’s not a question of strength. It’s all about timing, where you take the ball,” Rubenstein said. “Men would like to practice with me because the ball came back as hard as any man. They could practice defense. The Montreal paper called me ‘La Bondissant Petillant.’ I won the Canadian national championship when I was 28 and had three children.”

She credits her late husband, Marty, whom she married in 1956, with making her “a true competitor, Marty and a young man from City College, Irv Wasserman. Marty made me practice and taught me how to pace myself, they helped my game enormously. Bernie Bukiet, a Polish refugee national champion, who first fled from the Nazis and then from Russia, taught me how to block. . . . Marty Doss, the best coach in the world, taught me to pick my shot, and to pick it early. That’s how I was able to win the Canadian championship.”

Asked what it was she loved about table tennis, Rubenstein said, “I love competing. You go in knowing you can win or lose. I never cried when I lost. People would say they never knew whether I was winning or losing. Win or lose, I loved it. Pro athletes used to like to watch me play because I looked so happy.”

When she and Dzidra Lukina played in the 1963 world championships in Prague “it was the first time the Soviet Union and the United States had fielded a team in international competition.” They lost 3-2 in the semifinals to the eventual winners, Kimiyo Matsuzaki and Masako Seki of Japan. Their quarterfinal-round win over the French women’s doubles champions was recounted in an Associated Press story that went around the world under the headline: “Kennedy and Khrushchev Defeat DeGaulle.”

Those matches, as well as an account of Rubenstein’s Canadian championship, are mentioned in “The History of U.S. Table Tennis, Vol. IV: 1963-1970” by Tim Boggan. A photo of her and her teammates on their way to Prague in 1963 is on the volume’s back cover.

At about the same time, Rubenstein, who was later to teach philosophy at the graduate and undergraduate level, took a course in the history of ideas at City College New York with Isaiah Berlin, a philosopher, historian, and social and political theorist. “His specialty was the Enlightenment and Romanticism, which came after it. The Enlightenment was based on reason, Romanticism was based on feeling. The dangerous part of Romanticism was that it led to Hitler — it made him possible.”

While she had played in Tokyo and Korea, “there were a few times when I could have played in world table tennis championships that I didn’t go. I could have gone to India, to Sweden, Red China, with the Ping-Pong diplomacy team. . . . And I could have gone to many more national tournaments in this country when I was growing up. Why didn’t I? Well, I had no family support for one thing and I didn’t have the money to travel.”

Many years later, “I realized that I shouldn’t have said ‘no’ to things I should have said ‘yes’ to” — including an offer to teach philosophy at Duke University soon after moving here in the mid-1960s. “But that’s who I was back then,” said Rubenstein, who, in her 70s was to get back in the game as a world-class tournament poker player, which is another story.