From the late 1980s until the early 2000s, it would not have been unusual to see Sigrid Owen near Fort Pond or Hook Pond — large net or perhaps a bag of cracked corn in hand — on a mission.

Ms. Owen, who would have been 98 last Saturday, was a certified wildlife rehabilitator who helped over 500 swans in her lifetime. Her efforts earned her the nickname Swan Lady of the Hamptons and frequent mention in this paper, The New York Times, and Newsday.

She knew individual swans by their distinctive markings — a scar on the beak, for instance, or a bit of missing webbing on a foot. She saw to it that the local swans did not go hungry during especially cold winters, dipping into her own pocket to buy some 2,000 pounds of cracked corn in the winter of 1995 to feed swans frozen out of their traditional freshwater food sources. She came to the aid of the injured and even helped settle a swan turf war or two.

A founding member of the Wildlife Rescue Center of the Hamptons (now the Evelyn Alexander Wildlife Rescue Center) and its president from 1998 to 2005, “She loved all animals, especially her dogs, Noelle and Sophie, and also kept turtles,” according to her friends Doug Campbell and Valerie Hodgson.

Ms. Owen died on May 23 of last year. There was no service, and her grave at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Coram, where her son, Christopher, is also buried, is unmarked. She had no surviving family nearby — her son died on Oct. 29, 2024 — and it took months for some of her friends to learn of her death. She had been living at Windmill Village in East Hampton.

Sigrid Albers was born in Bremen, Germany, on Feb. 7, 1928. She grew up in Bremen and Dusseldorf and studied painting, drawing, and calligraphy at the Cologne Art Institute. She came to New York in 1952. “I loved it so much, so I decided to stay, and because of the visa I had, I could work,” she told The Star in 2011. She took a job as a maid while attending night school, then continued her studies at the Art Students League and New York University.

She worked in the art departments at Woman’s Day and Redbook magazines and as an art director at a Manhattan ad agency, where she met her first husband, Burt Owen, a photographer. Their son was born in 1962. After her husband was killed in a car accident in 1964, Ms. Owen took over his Midtown Manhattan studio, learning photography as she went.

Her second husband, Jack L. Pfeiffer, also an art director turned photographer, died in a car accident as well.

Working out of Mr. Owen’s former studio, it would be 10 years before Ms. Owen was able to establish a name for herself. “In the 1970s it was still a man’s world,” she said in the Star interview, but her list of clients would grow to include such companies as Lenox, Smirnoff, Johnson & Johnson, Clinique, and Esteé Lauder.

Mr. Campbell had been her photography assistant from the 1970s to the 1990s; Ms. Hodgson met her around 1989 and connected with her through watercolor painting. “She was my watercolor guru,” Ms. Hodgson said. “Her thing was: Paint what you feel, not what you see.” The couple remained close with Ms. Owen for decades and saw her regularly until 2020.

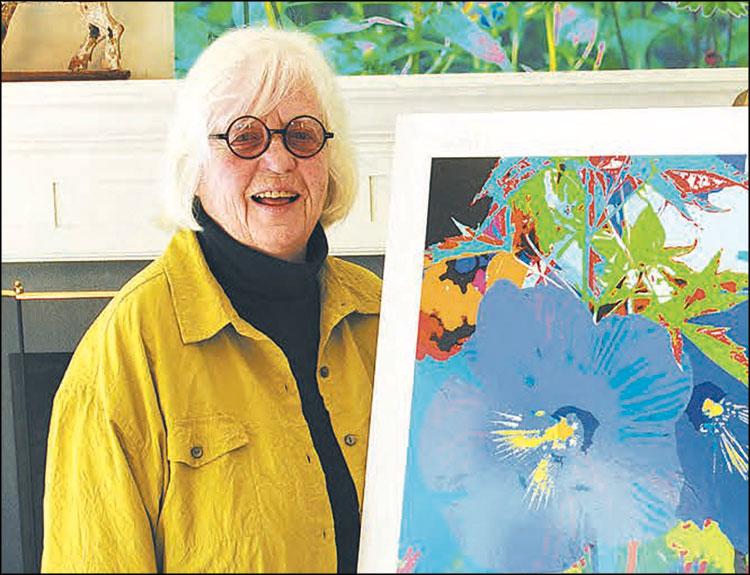

Undaunted by technology, Ms. Owen incorporated digitally manipulated photographs into some of her later artwork. She took up ceramics after her retirement in 2004, using the facilities at the now defunct Applied Arts School in Amagansett. “She really thrived in ceramics,” Ms. Hodgson said.

“All my years of experience are now focused on creating with clay. I love it!” Ms. Owen wrote in an artist’s statement on the website of the Mayson Gallery in Manhattan.

She continued to produce art into her 90s, selling her work at the Lazy Point shop on Amagansett Main Street, according to Mr. Campbell and Ms. Hodgson.

Ms. Owen bought a house in Montauk in 1974 and eventually moved there full time. She discovered her avocation on the South Fork. “I kept finding injured animals in Montauk, so I became a licensed wildlife rehabilitator,” she told The Star in 2011. Two swans that she saved, one she named Peep and the other Gloria Swanson, spent time recuperating in a pool on the South Fork and in the backyard of her Manhattan townhouse before eventually being released into a private preserve in North Carolina. “It seemed like I’d only just got things back to normal when another call came in. This time, a swan had been found with its leg broken, having flown into the Long Island Lighting Company’s high-tension wires at the commercial road edge of Fort Pond,” Ms. Owen told The Star in 1986.

“She was a fierce advocate for the center and for all animals,” Virginia Frati, the founder of the Wildlife Rescue Center of the Hamptons, wrote in an email this week. “She could be gruff; she didn’t take any nonsense if she didn’t agree with you on something,” Ms. Frati said.

As president of the center, Ms. Owen was instrumental in drawing notable supporters to the cause, among them the musician Paul McCartney and the actors Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger. “Paul McCartney had an injured butterfly hand-delivered to our center, naming it Billy Flutter,” Ms. Frati recalled. In addition to serving as president, Ms. Owen composed and edited the center’s quarterly newsletter and donated many works of art to its annual silent auction.

She sold her Montauk house in 2005 and moved to East Hampton, where she kept injured swans and geese in a backyard pond. “We used to go over to her house and help her put bandages on swans’ legs,” Ms. Frati recalled.

She also spent time in South Carolina, but even there, local people kept seeking her out whenever there was trouble with the South Fork’s swans. “She’s like Clint Eastwood with the swans,” the late Larry Penny, East Hampton Town’s former natural resources director, said of Ms. Owen after she’d helped out with a dispute among swans during a brief visit here in 2004.

“She is one of those people who does a great deal of good for the sake of it and not for any special status or recognition,” a friend, Daniel Thomas Moran, wrote in a 2009 letter to The Star after a picture of her feeding swans in the snow appeared on the cover of the paper. “I would bet that many of your readers saw that photo and knew immediately that it was Sigrid, the only woman who would be out in a driving snow to feed ducks and swans, and why — because they were probably hungry. And because, like every other day, they expect her.”