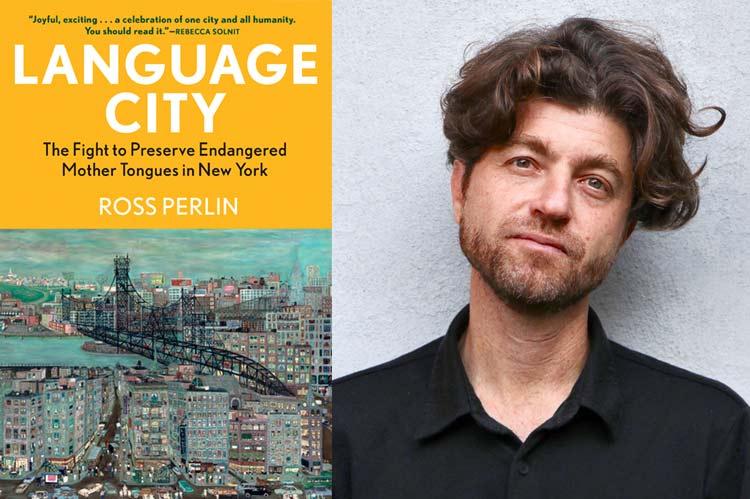

“Language City”

Ross Perlin

Atlantic Monthly Press, $28

Thank God for the Tower of Babel! Without it there wouldn't be linguistics. You might say that many of the polyglots who populate Ross Perlin's "Language City" failed to heed Proposition 7 of Wittgenstein's "Tractatus": "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent."

Mr. Perlin actually quotes the philosopher thus: "Die Grenzen meiner Sprache bedeuten die Grenzen meiner Welt." The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.

Here is what he says about Mandarin: "There seemed to be native words for everything, and few clear cognates with or borrowings from other languages. . . . Far from being ideograms that represent meanings directly through images, characters are intricately entangled with the spoken language." Yet he is, in fact, bemoaning the difficulty of learning a language like Trung, where "a world was slipping away even faster than the words that referred to it."

What happens to Bishnupriya Manipuri, a language from Bangladesh, Tsou from Taiwan, the Gabonese language Ikota, Russian Chuvash? Facebook may claim "to bring the world closer together," but human civilization comprises over 7,000 languages minus "dialects, sociolects, ethnolects, religiolects, and local varieties. . . . Languages are being lost every year."

The author quotes the linguist Michael Krauss that linguistics would "go down in history as the only science that presided obliviously over the disappearance of 90 percent of the very field to which it is dedicated."

Located in a "sunless canyon of Eighteenth Street," the Endangered Language Alliance, of which Mr. Perlin is director, is the repository of a vast trove of information about dying languages.

One of them, Seke, is spoken in five Nepalese villages "with seven hundred speakers, over a hundred of whom have moved to a vertical village, a single building in Brooklyn, as part of a vast new Himalayan migration of extraordinary linguistic complexity."

"Can Babel — the real contemporary New York experiment, not the Biblical myth — actually work?"

Escape was of course what brought many of these ethnic minorities to the city, whether it resulted from the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, or the genocides of the late Ottoman Empire. Kalustyan's, the famous spice store on lower Lexington Avenue, was started by Armenians, but is now the Bangladeshi-owned "anchor of 'Curry Hill.' " Ladino, meanwhile, is the language of "Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492."

Mr. Perlin's vivid appropriation of words constitutes a dialect in itself. "Porrajmos" is Roma for devouring — "in the Romani language Kalderash Vlax."

"Language City" is a linguistic Baedeker of New York, and particularly its outer boroughs, which have become a roosting place for so many immigrant populations. To the extent that it's about place as well as language, it's a work of ethno-anthropology and psychogeography as well as a study of language. Mr. Perlin produces a number of case studies of "vertical villages."

Linguistic diversity has historically always prevailed, though there is often little evidence of its existence. Oscan, Umbrian, and Etruscan must have been part of Imperial Rome. Then there were the Visigoths and Ostrogoths. In China the Xi'an Dynasty represented languages like Sogdian, Salar, and Tangut. Today there are the Kurds (Nashville), Hawaiians (Las Vegas), the Tai Dam (Iowa), the Arberesh (Sacramento), the Micronesians (Arkansas), the Zomi (Tulsa), the Karen of Utica, N.Y., and the Somali Bantus of Lewiston, Me., all of which make up what the author calls an "archipelago of refuge."

He writes: "The baseless and pernicious myth of Babel in Genesis 11 suggests that linguistic diversity is nothing but . . . divine punishment. . . . But in Genesis 10, the world was already diverse, with the descendants of Noah listed in a dazzling genealogy. . . . Even earlier in Genesis 6-9, Noah himself was commanded to safeguard the world's biodiversity in an ark."

"Language City" is a trove of wonderful epigraphs: "A language is a dialect with an army and navy," or "Language has always been the companion of empire." And colorful facts: "The Uzbek world in Brooklyn is split between Samarkandliks living near Ditmas Avenue (more likely to speak Tajik) and Tashkentliks settled near Avenues X, Y, and Z (more likely to speak Uzbek)."

If there are what Mr. Perlin calls "killer languages," it's no wonder that Putin would like to eradicate Ukrainian and make Russian the dominant tongue in annexed territories like the Donbas. In the course of the book, one learns that "Egyptian Christians . . . pray in Coptic, the last descendant of the pharaohs' language. In Flatbush and Gravesend, a few neighborhoods over, the world's largest community of 'Syrian' . . . Jews, estimated at forty thousand if not more, retains traces of a distinctively Jewish form of Levantine Arabic."

Elsewhere in Brooklyn, Pakistani languages include Pashto, Sindhi, Siraiki, Pothwari, "as well as the endangered languages of Pakistan's mountainous north (Balti, Burushaski, Kalasha, Khowar, Shina, Wakhi)."

Samuel Owusu-Sekyere of the Ghanaian Association of Staten Island "has an Ashanti father, an Akuapem mother, and an Mfantse wife, and he speaks Ga because he lived in Accra, plus a little Ewe because his parents were traders." Where is Ancestry.com?

Mr. Perlin's story is phrased as a personal one and a mission, and among its moving elements are the case histories of individuals caught in the shift of language and geography. "Today, mountain peoples the world over are coming down to the plains, driven by necessity and desire." In fact, "three of the world's major language families (Indo-European, Tibeto-Burman, and Turkic) come together at the Pamir Knot, a junction of the Himalaya, Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and several other mountain ranges."

Hasidic Jews appropriate Yiddish for their growing movement, while a Moldavian writer and editor named Boris, who reveled in the often irreverent Yiddish of Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade, feels the irreligious world in which the language originally thrived is being pulled out from under him.

"What does it mean to be a poet of an abandoned culture?" Mr. Perlin quotes the famous Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein as saying. "It means that I have to be aware of Auden but Auden need never have heard of me."

Loss is one of the major themes of "Language City," and the task of understanding New York as a repository of so many competing voices is often a Sisyphean task. "Maybe reform will come before more conflict does," Mr. Perlin remarks, "but it may be that every successful language movement has this secessionist drive inside it, that sometimes vicious little kernel of chauvinism or nationalism, and in some cases a literally religious zeal. Is it worth the price?"

Francis Levy's books include "The Kafka Studies Department," with illustrations by Hallie Cohen. He recently completed "The Wormhole Society," a graphic novel with illustrations by Joseph Silver. He lives in Wainscott and Manhattan.

Ross Perlin spent summers in East Hampton growing up. He worked at The East Hampton Star one summer when he was in high school.