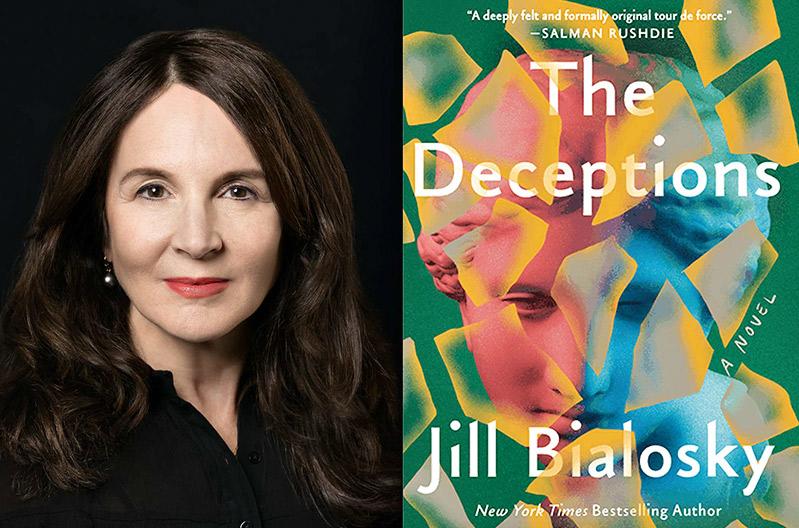

“The Deceptions”

Jill Bialosky

Counterpoint, $26

How unexpectedly poignant that on the cover of Jill Bialosky's new novel, "The Deceptions," is a quote from Salman Rushdie, who praises the work as a "deeply felt and formally original tour de force."

This also has the virtue of being almost entirely true.

Written in a first-person style that might be called "neo-diary" — punchy, intimate daily dispatches, along with some epistolary touches — the prose in "The Deceptions" comes in short bursts of insight from an unnamed narrator, a New York City-based writer and educator going through a middle-age crisis.

There is the son in college — a disorganized, erratic young man, prone to drinking and the occasional fistfight. He won't answer her text messages, and because their financial accounts are linked, she watches on her phone in real time as he racks up expenditures in a college bar. Eventually she will be obliged to fly to the small town where he attends school to help him clean up a brush with the law.

Her marriage to a research scientist seems to be unraveling, at least partly because of empty-nest syndrome. "The tension has been nesting, since our son's been gone, and now that we can't use him as a buffer, I fear our pent-up anger the last few years wanting to let loose."

The author is especially good on marriage — the silences, the loneliness of a long partnership, and the way familiarity and domesticity eventually smother joy and desire. "Marriage is a geological problem," the narrator explains. "Two forces of competing desires create instability in a rock formation." Later, when the relationship hits an iceberg, the narrator quips that it was not her husband that she hates, but marriage itself.

Enter into this atmosphere the Visiting Poet, as he is called. He is a writer of renown, come to teach a semester at the private school where the narrator is also employed. Physically, he is a kind of sexy lummox, large with "hairy knuckles," smelling of tweed and alcohol (almost certainly a simulacrum of Ted Hughes, once married to Sylvia Plath). You know there will be trouble from the moment the narrator first sees him.

"His face was honed. Something magisterial about it, in contrast to his pale skin, pallid, almost funereal, and large brutish hands, on his left a silver wedding band embedded into his finger, almost strangling it, as if it had grown too small over the years." He and the narrator will become friends, literary confidants, and, ultimately, flirtatious colleagues — all of which will end in disaster.

The great set piece of the novel is the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which the narrator visits almost daily. She goes for the monastic solitude and the sculptures of the Greco-Roman wing, constructing metaphors from its works in an attempt to unravel the dilemmas of her daily life.

A portrait of the boy Eutyches, for example (the novel helpfully includes pictures of these works), reminds the narrator of her son. "How gentle he looks. . . . Did I give more of myself to my son than I should have? Is this why leaving has left me empty?" A bronze statuette of Jupiter Capitolinus elicits this analogy: "It's my husband incarnate, the do-gooder, raising his fist, commanding, towering over me, declaring his decree."

More ominous is the statue of Perseus. "Oh dear lord. He's beautiful. It isn't fair. . . . Like Perseus, the Visiting Poet is tall, with a head of thick curly hair the color of slippery dark coffee beans." Uh-oh, she's got it bad, and that ain't good. In one hand Perseus holds a sword, in the other the head of Medusa.

The writing in "The Deceptions" is unfailingly lucid and forceful. Like the narrator, Ms. Bialosky has published a number of volumes of poetry, and that felicity is often manifest. The son, for example, has "dark hair and eyes the color of bark, and in a certain light the green of an unripe acorn." Sunk into an existential despair on a rainy night in her apartment, there is this: "The light descends. The building's panel of brick has withstood decades of weather and wear. The facade charcoal black like the walls of a prison."

On sexual assault, "The Deceptions" is almost eerily accurate, including the ambiguity between rape and consensual sex, and, in its aftermath, the victim's shame and confusion. "I thought you wanted it, he said. I looked at him strangely. I couldn't think. My body was frozen. . . . I wanted to believe him, forgive him, it was better than living with it, and slowly I relented. I wanted to make him feel better."

There is nary a word out of place in "The Deceptions," and there are long stretches of prose where nearly every sentence carries an almost electric charge.

Mr. Rushdie aside, however, the unabashed feminism of "The Deceptions" will, at times, try the patience of even the most self-flagellating male reader. There is much talk of the patriarchy, of course, and observations such as "The male species needs to evolve." (Women, you see, have completed the process.) "Men and boys," the narrator helpfully informs us, "are all babies at the core."

The term "mansplaining" — just the kind of glib jargon that should fall like an anvil on the ear of a poet — is employed liberally here by Ms. Bialosky.

Male characters don't come into much focus in "The Deceptions." We get, at best, brief flashes, mostly of a dark hue. A colleague at work named Mehta is a condescending ass who, we are told, is just jealous that she is a published poet. As for her husband, we don't know why she is so shattered about their fracture, since he is described as a kind of cypher — distant, porn-addled, and sports-obsessed. Her neighbor's husband, whom we never meet, ignores his wife — unless he is making demands on her to be "serviced." When Pynyon, a poetry critic, gives her latest book a negative review, it is chalked up to misogyny (in that great hotbed of misogyny, The New York Times).

The one exception is the Visiting Poet, whose character is in fact explored — he's a lost, shaggy dog, horny and self-pitying, in need of praise and feminine attention for his fragile ego. That's the best of him. Even the most inexperienced reader will know from the moment he enters the stage that he will become the narrator's rapist.

If this weren't enough, there is a second rape — this of a literary kind. It is a nasty, effective twist at the novel's climax that you won't see coming, and which arrives like a left hook.

Ultimately, "The Deceptions" feels like a novel by a first-tier talent keening dangerously toward an agenda. Ms. Bialosky doesn't really do irony, but how disappointing it is that the narrator, an avowed feminist, can't see it when accusing Pynyon of looking at her poems through the "male lens."

Can we agree that all lenses — or "isms," for that matter — applied to art are distortions?

And if not, what makes one lens better than another? Isn't it just the corollary of the same mistake?

It is perhaps this, and only this, that keeps the often superb "The Deceptions" from greatness.

Kurt Wenzel's novels include "Lit Life" and "Gotham Tragic." He lives in Springs.

Jill Bialosky is executive editor and vice president at W.W. Norton. She lives in Bridgehampton and Manhattan.