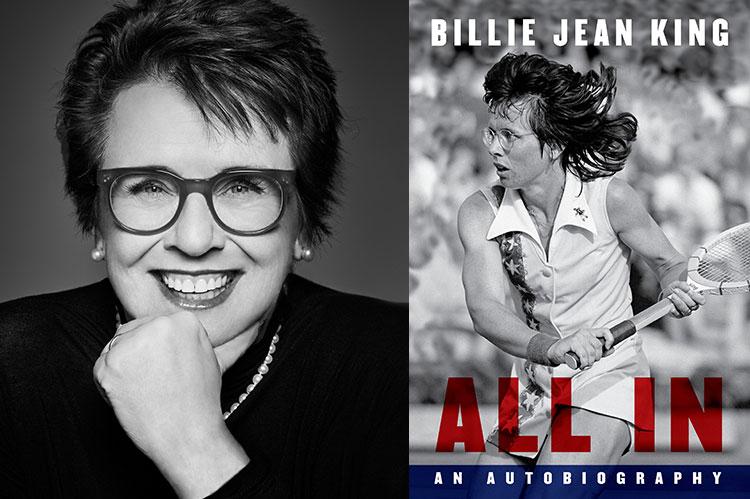

“All In: An Autobiography”

Billie Jean King with Johnette Howard

and Maryanne Vollers

Knopf, $30

In life, some say, love is all. In tennis it means nothing, naught, an egg-shaped zero — in points, games, or sets. After all, some also say, the term comes from l'oeuf, French for egg.

But love in tennis is far from naught when you consider the love a court champion like Billie Jean Moffitt King obviously has for her sport (from the very first kid's racket she saved for to her last backward glance at Wimbledon's Center Court), for coaches and fellow players (mostly), for her fans, for fairness and equal treatment regardless of gender or color, and after more agony and effort than you might imagine, for true understanding of her long-closeted sexuality and with it love for herself.

Though far from the first book by or about Billie Jean, including even a previous autobiography with the great sports scribe Frank Deford, "All In" provides the most current, candid, and personal perspective of a true champion in both senses of that word.

Through natural prowess, desire, and dedication, her career featured 39 Grand Slam singles and doubles championships, including a record 20 titles at Wimbledon, among a total of 126 singles titles, 36 women's doubles, and three World Team Tennis championships, with an international ranking of number one for seven of the 10 years from 1966 to 1975.

But it was not for her court triumphs only that the National Tennis Center in New York, home of the U.S. Open, was renamed for Billie Jean. She was also a champion in the other sense — an avatar and advocate for women and, ultimately, all "outsiders" in the traditionally white, male-dominated sport, through her persistent activism seasoned with sensitivity to the realities of public opinion, and the power of Big Tennis politics.

The opposition to King's campaigning for female players seemed unbelievably bone-headed and pig-headed while reading about it with at least half an eye on the recent U.S. Open, where so many of the women contributed the critical combination of physicality, personality, and entertainment that makes watching tennis so appealing.

Within the boys club of Big Tennis, and the "shamteurism" that permitted special benefits to male players "under the table" (to females not so much), several notable foes of women's advancement stand out, surprisingly at one point including even the breakthrough Black champion Arthur Ashe, though later a dear friend of King until his untimely death at age 49 after several heart attacks, two bypass surgeries, and transfusion-related H.I.V./AIDS.

Also former star Jack Kramer, a powerful opponent of more playing opportunities and more equitable prize money for women ("just good business sense," he wrongly believed). His selection as a TV commentator at her 1973 "Battle of the Sexes" match against the chauvinist hustler Bobby Riggs was reversed when King threatened not to play.

Decades later, seated next to each other at a formal dinner, Kramer confided, "I have a granddaughter now," which King "inferred" meant he had finally gotten her point.

Another villain was the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association official who threatened indefinite suspensions of female players who signed up for a breakout 1970 Virginia Slims-sponsored women's pro tournament in Houston — "a vague threat that implied we could be banned from making a living at the U.S. Open, Wimbledon, or anywhere else," King recalls. His name was Stan Malless, pronounced appropriately "malice." I checked on YouTube.

The tournament went on despite that and other threats, and King's dream of professional women's tennis proceeded apace.

As a 29-year-old star, Billie Jean steadfastly resisted challenges from Riggs, spry and tricky even at 55, until he upset the women's champion Margaret Court and a revenge match seemed necessary for the very future of women's tennis itself. "We've kept those women where they belong," he boasted.

Determined not to underestimate Riggs, as she heard Court had, nor the rigors of a classic men's five-set match to which they had agreed, King characteristically planned and prepped: a daily regimen of 200 sit-ups, 400 leg extensions with homemade ankle weights, 300 lobs against which to perfect her overhead smashes.

"I used the Maureen McGovern song 'The Morning After' to imagine how I'd feel once the match ended and I was the winner. I visualized myself playing Bobby and doing everything right. I beat him in my head a thousand times."

Many recall the pre-match psywar. King comes in on a gilded Egyptian litter ("The kind Cleopatra might've used. . . . I love it!") carried by six bare-chested athletes wearing gold arm bands and togas.

Riggs arrives in a rickshaw pulled by well-endowed young women dubbed Bobby's Bosom Buddies. He gives King a giant Sugar Daddy lollipop; she presents him with a squealing brown piglet in a pink bow.

Throughout the match, a fleeter-than-expected King makes Riggs strain, sweat, gulp salt pills, and ask for timeout for massage of a hand cramp. "I actually start feeling sorry for him now," she recalls. "I have a flashback to all those times I was so conflicted about beating men or boys that I lied to protect their egos. . . ."

Still, King wins in three straight sets (6-4, 6-3, 6-3) and beneath the ensuing bedlam hears Riggs lean in to confess, "You're too good. I underestimated you."

Over the years, Billie Jean would insist: "It was about social change, Bobby. . . . This was historical, what you and I did." When she called him a day or two before his death from cancer in 1995, he agreed, weakly: "We did make a difference, didn't we?"

Billie Jean also was one of the few top players to support 6-foot-2 Renee Richards, formerly a New York ophthalmologist, Richard Raskind, a five-time qualifier for the U.S. Open, Navy veteran, and family man, before extensive hormone therapy and sex-change surgery that got her banned from tournaments of the U.S. Tennis Association and the Women's Tennis Association.

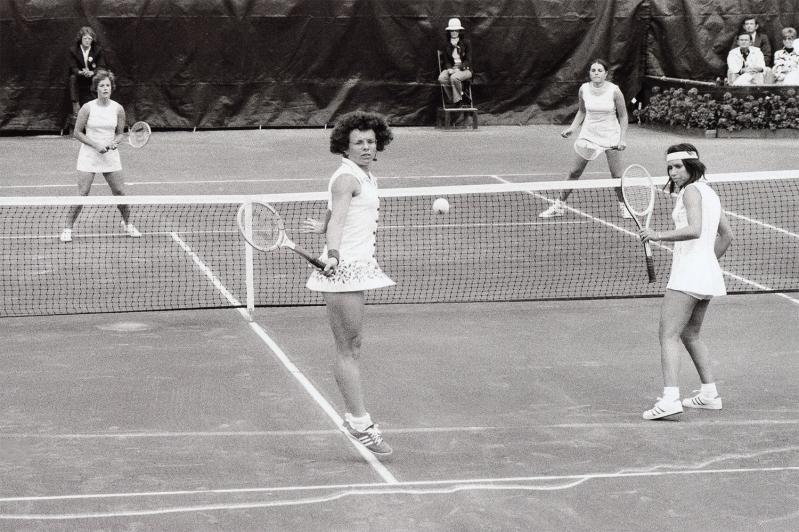

Accepting medical opinions that all those procedures left Renee "nowhere near as powerful as Richard had been," Billie Jean partnered with her for doubles at an unsanctioned tournament in Port Washington up the Island. They made it to the semifinals when the flu had Richards wanting to withdraw, panting, and, at one point, "practically sprawling on the ground," King recalls.

"That's when I turned to the stands, which were filled with her friends from Long Island, and shouted, 'This is the last time I'm ever playing with a Jewish American princess!' " Laughter erupted and the pair went on to take the tournament.

Off court, her own conflicted sexuality posed the most serious personal problems for King and her marriage to her college sweetheart, Larry King. "My attraction to women wasn't going away," she realized.

Her affair with Marilyn Barnett, a Beverly Hills hairdresser, later her paid aide, was at first a long-avoided joy "after years of nothing but tennis, tennis, tennis. . . . Our first time making love was scary but wonderful."

But Barnett eventually became a demanding mistress who saved their love letters as blackmail for what some called "galimony" when it came to court in 1981.

Her claims on the L.A. house in which Billie Jean and Larry let her live rent-free, and a share of the tennis star's income, failed. After several apparent suicide attempts, and developing cancer, she finally took her own life in 1997 at age 49.

But King was outed — "Such a soul-destroying violation and trauma for me" — and soon bereft of corporate sponsors. "I lost at least $500,000 in endorsements and marketing deals. In the long run I lost millions," she reports.

She also lost some respect for herself declaring that Barnett was her only lesbian affair, and concealing a newer, far deeper, romance with the daughter of a family she had met on tour in South Africa, Ilana Kloss, a "nice Jewish girl," later a prizewinning player herself, then Billie Jean's doubles partner, and eventually commissioner of World Team Tennis.

"The charade was excruciating. . . . I assumed that the world still wasn't ready to accept me as a lesbian — and, more to the point, I was still not ready to accept it myself," she admits now.

But as the times grew more accustomed to less traditional sexual identity, the scandal faded, Kloss finally talked King into several weeks of psychological rehab, and after four decades together, they were married secretly ("until the writing of this book") in 2018 at the home of former New York Mayor and tennis fiend David Dinkins.

Her always supportive ex-husband, Larry, still a sports promoter and sometime business partner, "played an enormous role in my life and career and remains a dear and generous friend whose recollections helped greatly in the telling of this story," Billie Jean writes at the end.

But the story continues. In her humanitarian, egalitarian works and in the inspiring legacy she began as a teen. Indeed, it was Billie Jean who handed up the women's singles cup at this year's U.S. Open after 18-year-old Emma Raducanu of Britain beat 19-year-old Leylah Fernandez of Canada.

"What a terrific display of competition and maturity from two exceptional players," King has commented. "It is wonderful to see this generation living our dream."

Johnette Howard is the author of "The Rivals," a book about Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova. She lives in Bridgehampton.

David M. Alpern ran the "Newsweek on Air" and "For Your Ears Only" radio programs for more than 30 years and now moderates presentations for the libraries in Southampton and Sag Harbor, where he lives, plays tennis, and practices with the ball-on-a-spring Billie Jean King Eye Coach.