In 1969, a year after his arrival in New York City, John Torreano first came upon small glass gems while walking on Canal Street. Three years later, when he was an artist in residence at the Art Institute of Chicago, the gems first appeared in his paintings. Gems, both glass and acrylic, have been a fundamental component of his art ever since. They have also spawned an almost infinite variety of polyhedral shapes in materials ranging from glass to plywood to metal.

Mr. Torreano believes that the meaning of an artwork happens in the interaction between the viewer and the object. The artist Richard Artschwager put it differently, calling Mr. Torreano’s artworks “paintings that stand still and make you move.”

During a career spanning almost six decades, Mr. Torreano has stayed true to his belief in the importance of perception while finding innumerable ways of expressing it. However, growing up in Flint, Mich., “It didn’t occur to me that you could be an artist until I took my first drawing class at Flint Community Junior College,” he said at his Sag Harbor studio.

That class was taught by Richard DeVore, a ceramicist who several years later became head of the ceramics department at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Mich. While in junior college, Mr. Torreano’s painting reflected the influence of Abstract Expressionism. “It suited my adolescent angst,” he said. Mr. DeVore and several other teachers at Flint helped Mr. Torreano get into Cranbrook, where he earned a B.F.A.

He landed a teaching job at Clarke College in Dubuque, Iowa, then still an all-female school. “I didn’t really know anything about teaching. I did okay, but I realized I wouldn’t be able to depend on making money as an artist. I realized I needed to learn to be a better teacher.”

Mr. Torreano entered the M.F.A. program at Ohio State, drawn there in part by Hoyt Sherman, one of the professors. Sherman applied Gestalt principles to the formalist analysis of painting, and Ohio State was the center of the Gestalt ideas about psychotherapy and visual perception.

While there Mr. Torreano executed a series called “Cutie Nudies,” which depicted Pop-ish women on plaid backgrounds. He compared those to Middle Age paintings, “where the figure of the holy image is primary and the grounds are usually abstractions in varying degrees. The idea of having the contradistinction between experiences in a painting has stuck with me forever.”

The figure disappeared from the plaid paintings after he graduated in 1967. While teaching at the University of South Dakota, he replaced them with the image of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent lights set diagonally across the plaid grounds. “I used to say when the electricity goes out in the gallery, my Dan Flavin will still be on.”

Within a year, he went completely abstract and embarked on a series of circular paintings, or tondos, some as large as 10 feet in diameter. In those the figure-ground relationship came forcefully into play as the plaid circles were overlaid with bands of white that ran to the edges of the canvas and met the white gallery walls.

“At first you see the white square as figure and the plaid as the ground. As you keep looking, once the white square closes visually with the ground, the plaid pops out. That’s a figure-ground flip.” Perception!

Mr. Torreano moved to New York City in 1968, where his Greene Street loft was across the street from Jennifer Bartlett’s. He quickly fell in with the generation that was about to take the art world by storm, among them Chuck Close, Lynda Benglis, and Joe Zucker. The following year he was included in the Whitney Annual along with Close, Ms. Benglis, Alan Shields, John Baldessari, and Michael Heizer, among others of his generation.

The painting he showed was called “T.V. Bulge” because, while flat, a rounded shape like a television screen from that period overlaid the ground and created the illusion of a bulge. It was one of a number of his paintings that offered a rejoinder to the critic Clement Greenberg, whose essentialist position was that valid painting should be about paint and flatness because illusion had become the role of photography.

“T.V. Bulge” was also one of his first paintings overlaid with dots, which were in a way the predecessors of the gems. “That’s when I got into this idea that where you were in relation to the painting determined how many dots you saw buried in the paint. It was including the viewer as part of the subject, the relationship between looking and the particularity of the position the viewer was in.”

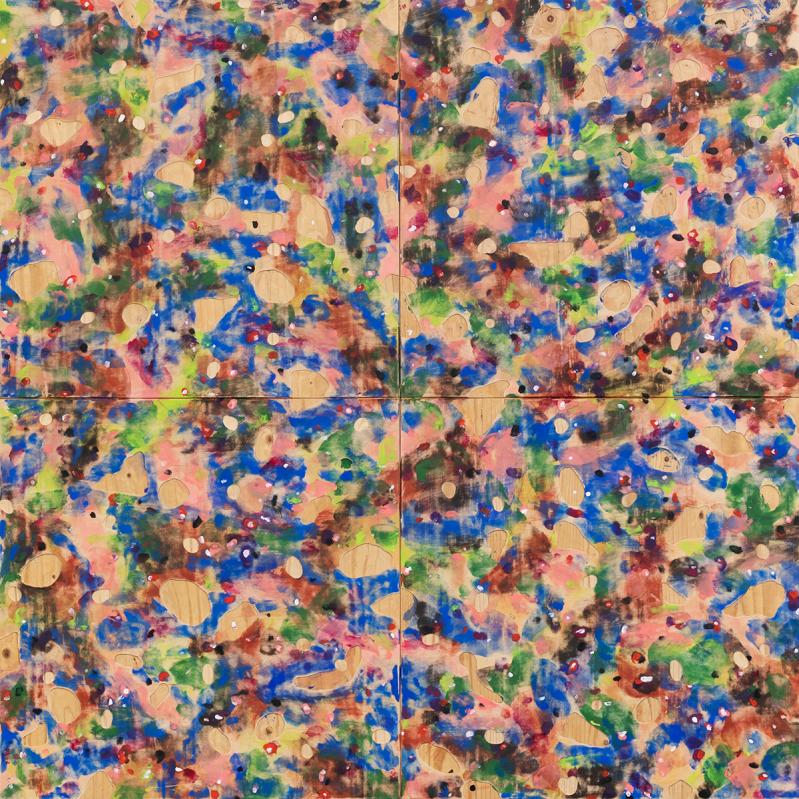

While in Chicago, the year the gems first appeared in his work, he was troubled by the somewhat arbitrary nature of the dots’ placement. Looking for an external visual source to underlie his choices, he had a revelation: “Stars! Duh!”

He assembled a few books on astronomy that were filled with images of the cosmos. He didn’t feel it was necessary to make pictures of the stars in the photos, but rather “to see interesting clusters and size differences and location differences.” As he began to dive more deeply into astronomy, he found another reason to oppose Greenberg’s essentialism: “The ideas of curvature in space and time. There is no such thing as flatness.”

In 1974, Mr. Torreano was chosen by Chuck Close to exhibit at Artists Space, an alternate exhibition venue in New York. For his works there he used wooden quarter rounds, normally used as molding, to frame the paintings and thereby emphasize the physicality of the object as it protruded from the wall. That physicality was in opposition to the illusion of the paint and glass gems.

Those works led the same year to his columns, which he has continued to make ever since. “I was sitting in my studio thinking my paintings took up a lot of space. I decided I had to make some narrower paintings.” By putting two quarter rounds together he made half rounds that he painted and embellished with acrylic gems. Some were as tall as eight feet, but only eight inches wide and four inches deep. “These tend to be more figural because they’re vertical. They reaffirmed the idea of mirroring the viewer as a figure.”

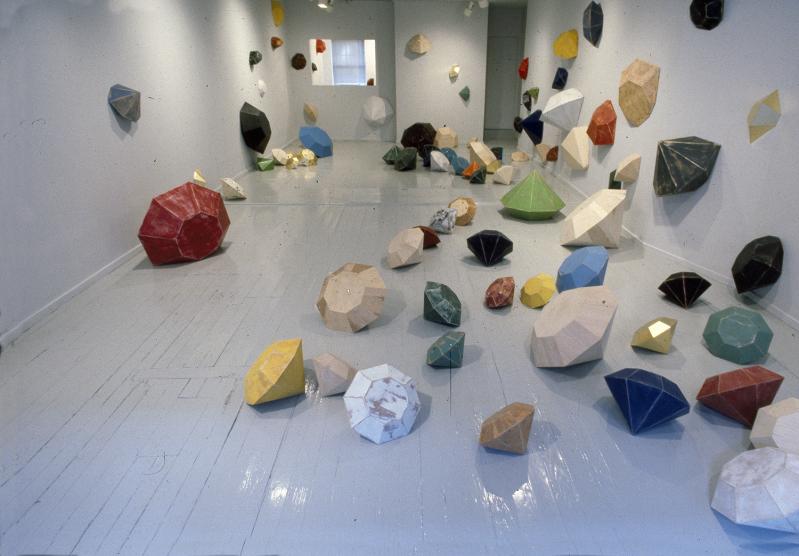

Plywood came into his work in the early 1980s. He was invited to show at Wave Hill, a 28-acre estate in Riverdale, and he decided to make large versions of the gems and distribute them on a hillside. A cabinet maker taught him how to make diamonds on a table saw, and they made 10 out of marine plywood and had 15 fabricated from metal.

Five years later he showed “100 Diamonds” at a gallery on the Lower East Side. All were made of plywood, many with gems affixed. Some were designed to look as if they were going into the wall, or coming out at odd angles, while others were distributed on the floor.

Typical of how certain themes run through his work while at the same time taking a variety forms, in 1992 he went to Dale Chihuly’s Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Wash. “They gave you a crew. When they asked what I would like to do, I asked if we could make glass versions of the wood diamonds and turn them into bases.” The polyhedrons included rhomboids and rhombexes.

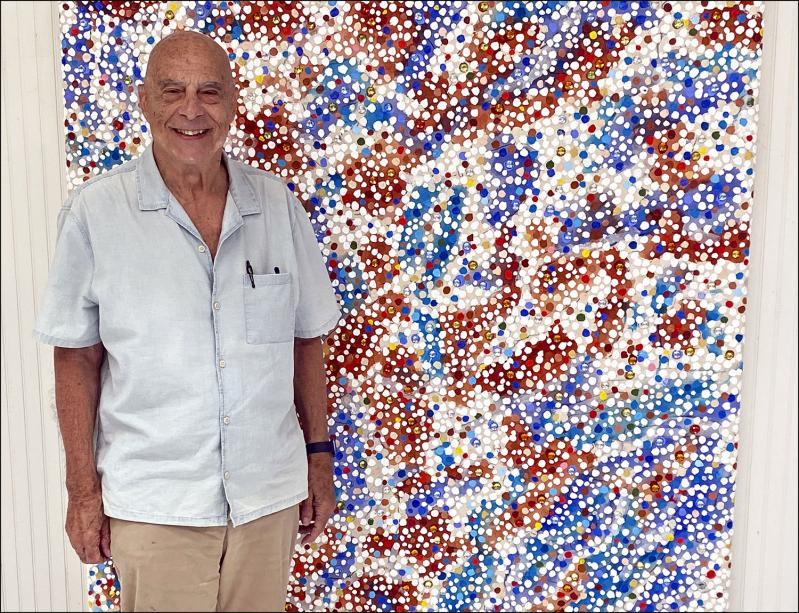

Recently, a friend of Mr. Torreano’s, who has worked for the film director Hal Hartley, wanted to do a film of him making a painting from beginning to end. “All along he had four cameras going, and we’re talking about what I’m doing with the painting, but also about art.” The finished painting, a vibrant swirl of dots and colors, now adorns a wall in his studio. The film will be submitted to the Tribeca Film Festival next year.

Mr. Torreano managed to find time between his studio practice and longtime teaching position at New York University to write “Drawing by Seeing,” published by Abrams Studio in 2007. The book offers an opportunity to dive more deeply into his ideas about the relationship between art and perception.

He first came to the East End in 1968 as the first visual artist in residence at the Edward Albee Foundation in Montauk. In subsequent years he visited the area and stayed with friends.

In 1992 he and his wife, Jodi Panas, an artist and psychotherapist, decided to buy a house in Sag Harbor. They divide their time between there and their space in TriBeCa.