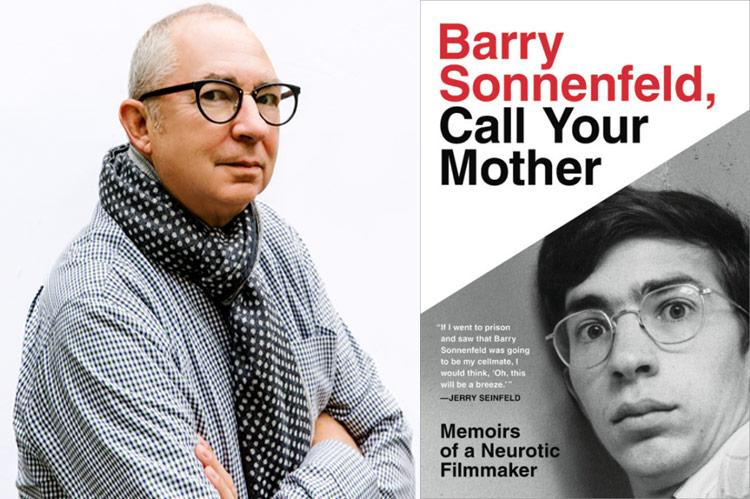

“Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother”

Barry Sonnenfeld

Hachette, $29

Well, he’s not that neurotic.

Despite giving his book the subtitle “Memoirs of a Neurotic Filmmaker,” and having endured a hellish childhood — a mother who sounds certifiably nuts, and a father who was sly, dishonest, adulterous, and a compulsive liar who actually stole money from his son — about the only neurosis Barry Sonnenfeld brought with him into adulthood is his fear of flying: “Every time I get on an airplane, I view it as a failed suicide attempt. I blame my mother.” (I’m nervous too, but I blame Boeing.) Barry blames his parents for everything that’s gone wrong in his life — not without some justification.

But a lot has gone right for him. Mr. Sonnenfeld, as movie buffs know but the general public might not, was a Hollywood cinematographer who graduated to directing, which seems a very natural procession. Always fascinated by cameras, he started taking pictures as a child, and had the good fortune to be mentored by the famous still photographer Elliott Erwitt (he also stole Erwitt’s wife and married her, but that came later).

Even better, the Coen brothers were his classmates in N.Y.U.’s graduate film program. They chose Mr. Sonnenfeld as their cinematographer on “Blood Simple,” their first film, and some of the reviewers went out of their way to praise his work as well as theirs, so the rest is history, though Mr. Sonnenfeld’s view of his own history is a mordant one: “Regret the past. Fear the present. Dread the future” are the words he says he lives by, despite having fashioned a very nice life and career out of the shambles of his youth.

The traumatic event of his childhood was being abused by Cousin Mike the Child Molester, a relative of his mother’s whom she invited to live with the family even though she and his father knew that he was abusing Barry, and other children as well, on a regular basis. When, as an adult, he confronted his parents with this fact, his father explained, “I never thought Mike was molesting you. I only thought he was playing with your penis.” His mother added, helpfully, “Back then child molesting didn’t have the stigma it does now.”

But his father also gave him some good advice: “Decide what will bring you pleasure in life and figure out how to make money doing it.” Dad himself got the pleasure part right but not the money; Barry succeeded at both. He seems to have enjoyed the cinematography more than the directing. The book will greatly appeal to camera geeks (like me); it’s full of information about film and filming, only a little of it technical. It helps to know what a wide-angle lens is, since Barry’s signature was to shoot everything with one, then dolly in and center the image, forcing the viewers “to look exactly where I wanted them to.”

When I read that, I immediately watched “Blood Simple” and “The Addams Family” (his directorial debut) on Netflix, and though I couldn’t tell how wide the angle was, my eyes seemed to go where he wanted them to. One of the ancillary pleasures of this book is that, caged by Covid as we are, we can punch up Netflix or Prime and remind ourselves how much fun his two “Addams Family” films are, along with such gems as “Men in Black” and “Get Shorty.”

What we’ll never get to see, sadly, is any of his first four cinematographic projects, which were full-length porn movies (hey, he had to eat), about which he goes into great and salacious detail in what is the funniest section of the book. He has the knack of making anything sound funny, like his mother’s recipe for egg salad: Put four eggs in a pan with a little water and turn the burner on high, retire to bed with a headache, and forget the eggs until they explode all over the kitchen ceiling.

In a more serious vein, he claims to be the world’s best leg wrestler, and has the wins to prove it — his effortless victories over the likes of Will Smith, Neil Patrick Harris, and the most skillful of all his challengers, Kelly Ripa, of all people.

Of course, he’s rightfully proud of his film work as well, and about photographing movies in a very organized way, with elaborate storyboards and copious notes. All his careful planning made possible, for example, the shot in “Raising Arizona” of two dozen people seated at a long Thanksgiving table down the center of which the camera tracks, resolving into a close-up of Holly Hunter and Nicolas Cage seated at the end, backs to the camera. Also much praised by aficionados was the iconic “bullet holes in the wall” take in “Blood Simple.”

Life was less simple when he turned to directing; he had to deal with the giant egos of producers and studio execs and movie stars and worry about budgets and schedules. But there were compensations. When the producer Scott Rudin hired him to direct “The Addams Family” because he was looking for “a visual stylist,” he got to work with wonderful actors like Raul Julia and Angelica Huston, and his editor on many projects was the hallowed Dede Allen, from whom, he says, he learned everything worth knowing about moviemaking.

Barry didn’t hire himself as his own cinematographer on any of the films he directed, though he insisted on designing all the shots and the lighting, and even choosing the film stock. And no panning, he insisted. Panning is the lazy way out. “I love to track but hate to pan,” he writes, and shooting wide-angle makes that a necessity.

As a writer, Mr. Sonnenfeld leans heavily on dialogue, as one might expect, but his powers of exposition are impressive too. Consider this description of his emotionally manipulative mother, who guilted him constantly and often threatened to kill herself, starting when he was 5: She “had the same control over her tear ducts that Mariano Rivera had of his cut fastball. She was the master relief pitcher of the sob.” That simile blew me away.

You can sense him gaining confidence as he matured, acquiring chutzpah along the way. He once paralyzed a studio boss with fear by telling him that “The Addams Family” was going to be just like “Sophie’s Choice,” only sadder. And in a Times interview, he told the world that he hated his mother.

Eventually he settled into some semblance of a normal life — happily married, father of three, living in East Hampton. Then his mother died, and eight days later, his serial-philandering father married one of his girlfriends — two events that left him without many regrets. More important to Barry was the death of Cousin Mike, which gave him great joy but caused him to devote the end of the book to a reprise of the molestation, which is tough reading but makes Barry a very real person. This is both a serious and a comical book — sort of like “Sophie’s Choice,” only funnier.

Richard Horwich taught English at Brooklyn College and New York University. He lives in East Hampton.