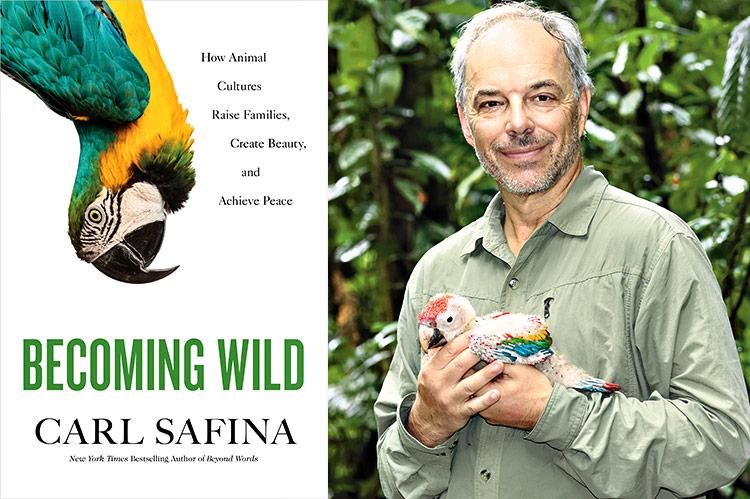

“Becoming Wild”

Carl Safina

Henry Holt and Co., $29.99

Animals can live without harming the Earth, why can’t we?

Carl Safina’s books are journeys into his wonder at the magic and mystery of the natural world, and the wonder of life itself.

“Look at these marvels! Open your eyes, listen, feel,” the ecologist and writer is saying as he takes us into oceans, deserts, and forests. “This is too precious, too wonderful to be missed — and to be lost.”

We are in the era of mass extinctions — the sixth, by some counts — and this one is being created by one species, us.

Mr. Safina is among those standing in our way — and beseeching us poetically and tirelessly to hear what nature is saying. His chosen tool is sharing his deep love of life on Earth. Which is why reading his most recent book, “Becoming Wild: How Animal Cultures Raise Families, Create Beauty, and Achieve Peace,” is so difficult.

With Mr. Safina, who takes us into the sea off Dominica, and to the jungles of the Amazon and Uganda, falling in love with the diversity and beauty of life on Earth comes easily. But love is not enough. Stopping the vanishing of the object of our affections is elusive. This, ultimately, is the painful challenge of “Becoming Wild.”

For this, his eighth book, Mr. Safina, who lives in Amagansett when he’s not teaching at Stony Brook University, spent months with scientists observing and studying sperm whales, parrots, and chimpanzees. These are animals that over thousands of years crafted lives — how they mate, how they communicate, how they eat, how they enjoy themselves (because they do that, too) — to fit into the world they inhabit. One could call their choices sustainable. Why have humans not done this, he asks. Why are we “the only species on Earth that makes choices that are bad for our species?”

He doesn’t answer that question. Rather he carefully shows us the vast array of ways in which many species — but particularly these whales, parrots, and chimpanzees — have succeeded in creating family, safety, community, fun, and the means for healthy survival. He points out that many of the traits that enable animals to achieve their best selves can be viewed in human terms. We would call their obvious intelligence and intuition and their abilities to share information distinctly human, as we would their sadness, joy, humor, empathy, playfulness, their kindness, loyalty, fairness, forgiveness, reconciliation, and so on. All human, we would say.

And yet animals across the globe have all those traits. So, by any objective measure, they’re not human traits at all, and it is ingrained human arrogance to think so. In fact, the traits — both the ones learned and passed down to survive, along with the ones that make life beautiful and fun — belong to those species all on their own.

“Parrots have been perfecting parrotness for . . . fifty million years,” Mr. Safina writes. “These beings have all been here, continually honing who they are, through spans of time that are essentially impossible for human minds to fully grasp. It’s been a long, strange trip. But here we are, all together now.”

So much for being surprised when a chimpanzee mother mourns her dead infant by clutching it to her breast as a human might, or when a mother orca was found to have pushed her dead calf for 17 days in an act of desperate grief. Those familiar-to-human feelings belong to all living things, although to some more than others.

Mr. Safina listens to sperm whales as they click the call that is their very own, one that identifies their clan, their tribe, if you will, another that identifies each individual, and yet another to signal a deep dive. The sounds made by the sperm whales he visited make up an entire dialect in a language spoken by sperm whales around the globe.

In the Amazon, beautiful parrots sing to one another to attract mates, claim territory, or just because it’s amusing. Mr. Safina joins them at their local “bar,” a clay bluff, and watches them socialize where he observes them quite literally filled with all the emotions of a good life on Earth. “The macaws aren’t hanging upside down while flapping and squawking with their friends for nothing.”

In Africa, he lives among rough-and-tumble chimpanzees, who love and cuddle, and who go to war because that’s what the male ego requires. Amid them Mr. Safina finds all that is right and all that is wrong with man. Chimps aren’t like men; men, in fact, are like chimpanzees.

“It’s not just that chimps remind me of human beings,” he writes. “They remind me of something worse; they remind me of certain men I’ve known. The tedious ridiculousness of chimp male dominance highlights the tedious ridiculousness of the dominance obsessions of too many human males.”

Hundreds of species are under pressure. Pollution and loss of habitat and food sources, all man-made, are killing nature. There are some hopeful signs, and Mr. Safina shares them, but if this book offers any hope it is in the insight that what is being lost is more than diversity of natural life — which, by the way, should be enough to get humanity to wise up now and stop the ceaseless decimation — but rather whole languages, songs, problem-solving skills, laughter, dance, love, and perhaps the most important one: the ability by many species to recognize what it takes to live without messing it up for everyone and everything else.

“Whale . . . groups have specialized in differently answering the question ‘How best can we live where we are?’ Why aren’t we asking ourselves that question?”

This is no breezy read. It’s dense with minute observations and the day-to-day notes from Mr. Safina’s outings. But it is laced with history and salty references — from Herman Melville to Peter Matthiessen — and wisdom from a man who it seems is as much a scientist as a philosopher.

“If we had the courage to be honest about it, we would have to admit that whales and birds and apes and all the rest live fully up to everything of which they are capable,” Mr. Safina concludes. “And we, regrettably, fall short of doing that. For them, to be is enough. For us . . . nothing is enough.”

And yet, he says, “there is so much of the world to know and love.”

“Becoming Wild” is a warm and beckoning paean to our natural world. Mr. Safina’s deep understanding and love resonate, even if we are left bereft, with the angst and fear that our own love will not be enough.

Biddle Duke is the founding editor of The Star’s East magazine. He lives in Springs.