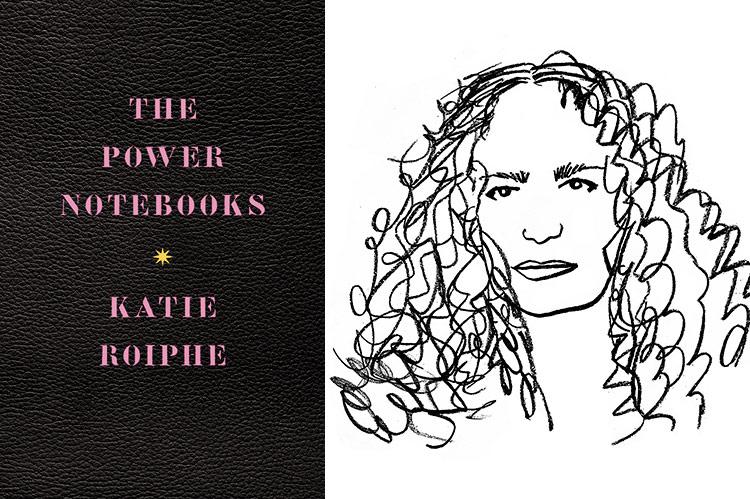

“The Power Notebooks”

Katie Roiphe

Free Press, $27

Katie Roiphe burst on the cultural criticism scene in 1993 with “The Morning After: Sex, Fear, and Feminism on Campus,” her controversial work on what was termed the rape crisis. Back then, some feminists felt we were all supposed to choose up sides. Some still do, though the names assigned to the issues have changed. And now we have hashtags.

A spokesperson, or a lightning rod, or a pot-stirrer, Ms. Roiphe defines some of her work as “arguing against received ideas.” Other works, however, are methodical research projects, relevant to but not defined by the current moment, and not incendiary.

Ms. Roiphe is a mother, a university professor, a partner. These roles swirl through the brief, titled, fragmentary sections that make up the work at hand, her seventh book, a pieced-together group of contemplations about personal power dynamics.

“The Power Notebooks” is quite different from her earlier works in terms of structure and intention (she’s not setting out to prove anything). In terms of content and subject matter, however, the book is something of an extended dance remix of Ms. Roiphe’s own previous work.

For instance, she draws on her 2007 study “Uncommon Arrangements: Seven Portraits of Married Life in London Literary Circles 1910-1939,” rehashes her essay “Beautiful Boy, Warm Night,” discusses the turmoil surrounding her 2018 essay for Harper’s on the #MeToo movement, and references “The Alchemy of Quiet Malice,” an essay in which she defends single motherhood from moralistic derision. She maps concerns, preoccupations, and hunches; she’s been to many of these places before. Some she’s attempting to chart fresh, exploring toe-path connections to the whole.

In her author’s note, Ms. Roiphe is explicit about what this book is not: “Please note that when I use the word ‘power’ in these pages I don’t mean geopolitical power, or socioeconomic power or electoral power, or power in the broad Foucauldian sense.” What then? Power dynamics between individual people. She is specific about a particular preoccupation: “women strong in public, weak in private.”

The abjection — her frequent word of choice for lack of personal assertiveness/powerlessness — in the romantic lives of Simone de Beauvoir, Jean Rhys, Sylvia Plath, and Edith Wharton, among others, is a subject of Ms. Roiphe’s dogged fascination. She examines. She quotes. She questions: Are some forms of abjection chosen? E.g., wild, abject passion for a love interest. Is there power in this sort of passion?

When Ms. Roiphe turns examination upon herself, strong in public means strong on the page, and weak in private means, not exclusively but often, weak amid power dynamics with her love interests. Three relationships in addition to several other romantic interludes and episodes are sketched out in the book. H. is her first husband, the breadwinner for a time in her life, and the father of her daughter. “The Claw” is an older man, glamorous in his lack of attachments, with whom she has a prolonged uncommitted relationship. Tim is her current husband, an artist and a recovering addict (a number of sections related to Al-Anon meetings emerge as thought experiments on ceding control).

Perhaps the pivot of the book can be found in Ms. Roiphe’s relationship with H. She returns periodically to a particular incident chronicled early on: The couple’s overtired baby is wailing as the family drives home from an outing; tension mounts as the baby continues to cry, and then, over a mile from home, H. swerves to a stop and orders Ms. Roiphe out of the car. She gets out and walks home carrying the baby in her arms.

Ms. Roiphe’s tone is cool and detached throughout her description of this incident and over the course of the book. Yet she is also tortured unto labyrinthine machinations around the implications of this and other episodes that bespeak her lack of power. The interpretations and counterinterpretations spin out and back around. All are elegantly phrased; some coalesce into clarity you can really put in the bank. From a section titled “Abusive”: “The word abusive strikes me as impossible, not just because of what it says about H. but because of what it says about me.”

As it happens, this self-same man, after their divorce, shows himself to be a kind, warm, generous co-parent. Phew. In recording this happy development, Ms. Roiphe also obviates, or at least contains, her experience with a man who may or may not have been abusive. We need not pity the person whose ex-husband is so devoted, need never call her abject. In fact we might envy her.

Thus Ms. Roiphe moves down a twisty road, turning from her powerlessness to demonstrate her dominance, consciously or unconsciously, probably the former, given the level of self-examination in the book. She seems to have all angles covered, including protecting herself from powerlessness even as she makes an honest go of relating incidents of same.

In a section in which she writes about telling her story to a friend, she delivers the conundrum: “Somewhere in the process of turning my romantic history into a story, I have drained it of any signs of me being crushed. I have taken out any heat. I have elaborately narrated being powerless without somehow showing any powerlessness.” She traffics in protective distance as a kind of power. She knows it. She tells you she knows it.

The issue of vulnerability, especially as it relates to likability, is one of Ms. Roiphe’s fixations. Characterizing “ ‘I-am-a-mess’ moments” that make (women) writers “relatable” as “deferrals of power,” she proposes that a self-effacing element — e.g., a crying scene — would do the trick to produce the vulnerable, likable, relatable quality that eludes her, but she declines to go down that road. On the flip side: She analyzes, agonizes. From a section titled “Unlikable”: “Because I see all of this quite clearly, one might very reasonably wonder why I can’t fix it. If the unlikable woman can be liked, wouldn’t she choose to?”

The format — or strategy — of the volume written in fragmented sections has been heartily welcome in Maggie Nelson’s “The Argonauts” and Kate Zambreno’s “Heroines,” both singular tour de force feminist works around identity and power that also get very personal. There is certainly contemporary precedent for Ms. Roiphe’s effort, though this project is inconclusive by both admission and design.

She describes her experience of working toward what would become the current volume: “The notebooks required me to do things I otherwise never let myself do: admit weakness, give up control, acknowledge doubt, have no idea where I’m going.”

The “give up control” part? Well, debatable. She might have no idea where she’s going, but she’s put herself behind the wheel and she’s quite determined to drive the car nonetheless.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Quit.” She lives in East Hampton.

Katie Roiphe has spent many summers in Amagansett, where her mother used to have a house.