When I was a college student I worked one summer at the Gotham Book Mart on West 47th Street. I got the job through E.E. Cummings’s wife.

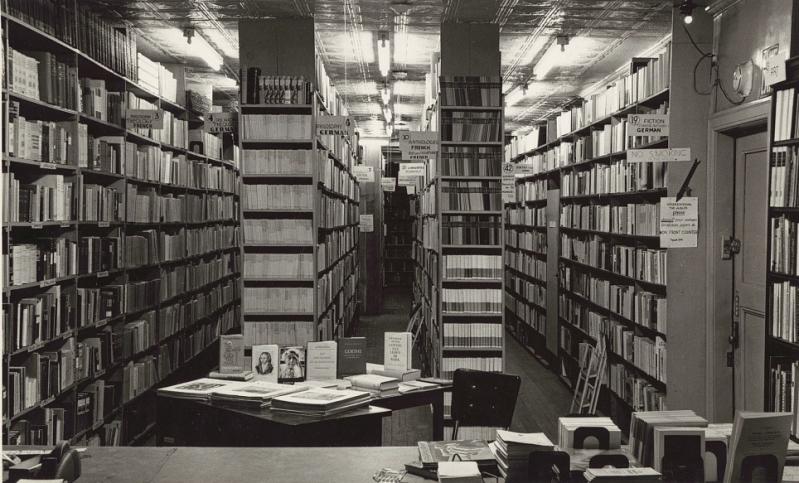

The Gotham was a kingdom for writers, scholars, and students. It kept an array of old and new books, literary journals, and even artworks by writers who fancied themselves as talented painters, such as Cummings and Henry Miller. The walls were a photo gallery of 20th-century authors. Upstairs was the James Joyce Society. It was a pleasant, disorganized, ramshackle store for browsers and eccentrics and literary lions: I had seen Arthur Miller, Philip Roth, and Woody Allen there.

Two years later, I worked at the Doubleday Book Shop on Fifth Avenue and 53rd Street. I also did the accounts receivables at that bookshop.

The Gotham and Doubleday stores were centuries apart. While the Gotham was a haven where one could find rare books, including ones that were more than a century old, the Doubleday was stacked with the latest best sellers. All books were perfectly organized: hardbacks by category and alphabetized by author were in the front; paperbacks in the rear, also systematically organized. During the Christmas season, the store made more money in four weeks than it did all year. The Gotham, though, was less a source for holiday gifts than for difficult-to-find, out-of-print titles. I got quite a few first editions by some of my most cherished authors there.

Following my graduation, I moved to the Upper West Side, where I found a used bookstore named Parnassus. It was run by a red-bearded devotee of D.H. Lawrence named Stanley Lewis. The store smelled of his pipe tobacco and faintly of cat urine.

Stanley used to go to England and Scotland twice a year on book-buying ventures. He always came back with boxes of books. He sold me a couple of Lawrence novels and tried to sell me a complete set of the literary journal The Yellow Book. I could not afford it. He was also a fan of Wyndham Lewis. I disliked Wyndham the man, and found his books pretentious and in some cases poisonous.

Stanley did get me involved in one of his ventures. He started a publishing company that sold literary bibliographies to college libraries in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He would solicit library science majors to turn over bibliographies of such writers as Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Frost, et al. He made successful deals, advising them that once their bibliographies were published they would find it easy to get jobs as college librarians.

Once he got a bibliography, he would put an ad in Library Journal announcing its publication and offering a 10-percent discount on any preorders. The money rolled in, and Stanley now had sufficient funds to pay for the publication. Other sales subsequently came in. I invested a small amount of money and was handsomely rewarded in this venture.

Stanley went on without me after a few successes and then sold his imprint to an educational publisher. From there, Stanley started a poetry journal, and as expected he titled it Parnassus. He was able to get sufficient grant money to make a profit, and he subsequently sold it. Neither Stanley nor his little bookstore on West 88th Street continues to exist.

One block north and on the other side of Broadway was the New Yorker Bookshop (no relation to the magazine). The store was on the second floor above a small newspaper shop. One ascended on rickety, uneven steps that emitted the sounds of crickets.

The news store and bookstore were owned by Peter Martin, who had been a founding partner in the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco. He was the stepson of an antifascist newspaper editor named Carlo Tresca, who had been assassinated by a mafioso, Carmine Galante, in New York during World War II. The hit had been ordered by Vito Genovese as a favor to Benito Mussolini. Peter looked like Abel Magwitch, the weather-beaten escaped convict in Charles Dickens’s novel “Great Expectations.”

Peter frequently and loudly expressed his political opinions in reaction to newsworthy events that would cause his face to turn the color of a beet. The store did not have to make money, because — as I was told (and I don’t know if it’s true) — the owner’s wife, Madeleine Dimond, was descended from a family of considerable wealth, and her generosity kept the door open and the lights on. She was a highly regarded abstract painter, though I never saw any of her paintings in the store.

I got the impression that she let her husband run the store as if it were a hobby. And he stocked it as if it were his own library: lots of books on politics and literary criticism. I visited frequently and enjoyed browsing its shelves as if peeking into the life of a singular book lover.

Those bookstores are all gone, replaced by large chain stores in malls that carry the same books. I visit those stores, though not often, and I rarely find a book that was published more than a year ago. The turnover of titles is like perishable fruits and vegetables in a supermarket.

Jeffrey Sussman is the author of 17 nonfiction books, most recently “Tinseltown Gangsters: The Rise and Decline of the Mob in Hollywood,” due out in March from Rowman & Littlefield. He lives part time in East Hampton.