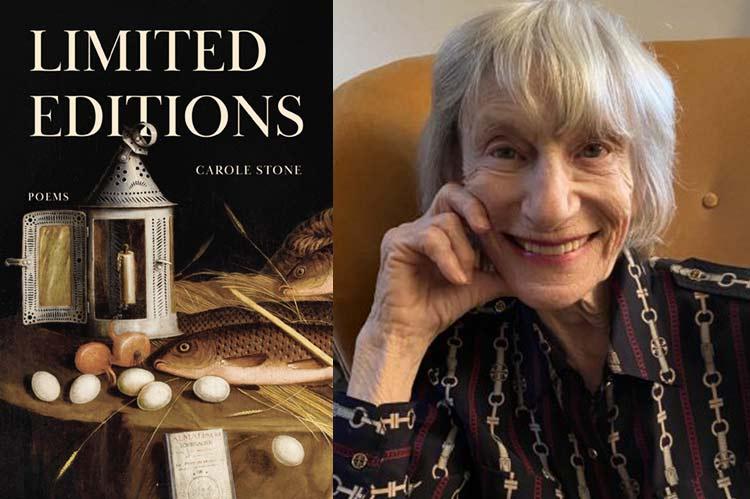

“Limited Editions”

Carole Stone

CavanKerry Press, $18

With "Limited Editions," her strong new book of poems, Carole Stone shares with readers poems about her life with her husband, poems of his illness and death, and poems of her widowhood. Stone presents all of these poems as if they were, to use Wordsworth's phrase, "recollected in tranquility."

The poems — brief, spare, and economical — often end in their closure with surprising, insightful, and occasionally profound observations. Given the underlying sadness of such a collection, it's remarkable to find no keening, no cursing God, no finger-pointing, and, especially, absolutely no self-pity.

The collection's first poem, "Fortune," featured as a prologue to the rest of the book, encapsulates all the qualities inherent in the collection. The diction is simple, direct, accessible. The title refers to the cookies people often get with their Chinese food, and it begins by apostrophizing a small share of her audience, "Dear dying / and dead," begging forgiveness for her "daily wants." But this is no apology; by poem's end the speaker eats the paper fortune, "I bite down hard," indicating an intention to internalize the future and survive, as difficult as that may turn out to be. I recommend that readers return to this poem when they've finished the book.

Structured in five sections, "Limited Editions" begins with poems concerning the couple's relationship and marriage. In poem after poem, Stone employs a line or two that subtly foreshadow her husband's dying and her subsequent grief and inability to alter the inevitability of his death. In "Long Marriage" she writes in the penultimate line, "I want to know why peas need a fence to lean on," metaphorically asking why two people in a marriage require each other's support. In "Farmer's Market," Stone tells us that "the Polish vendor," "he'll be here all winter" (are any of us guaranteed to outlast any season?).

In "Flamingo," the plastic bird bought at a yard sale 20 years prior that gets hauled to the dump becomes a symbol of our transience. Finally, in "Pairs," Stone writes about reading "Anna Karenina," stating, in the final line, "But I can't change the ending," another line foreshadowing her inability to control the outcome of her husband's illness.

Section two includes poems about her husband's sickness and death. One of this section's — and the book's — finest is "Underworld," wherein Stone views her and her husband's descent into the subway as a metaphor for entering the afterlife, the beginning of a classical katabasis. Here, the other commuters "pass through the turnstiles, / like shades." Here, the dark, urinous platforms and tracks contain those who will soon be "immortal" when "their connection comes." The subway train becomes the modern equivalent of Charon's skiff. It's death, finally, that ensures our immortality because once we die we no longer are subjected to death's arrival.

The collection's final three sections focus on the poet's coming to terms with the loss of her husband, and finding a way to move on. Taken together, these poems form a primer of sorts on the resiliency of the human spirit.

In section three the ironies begin to accumulate. In "Vanilla," the speaker tells readers that vanilla, unlike people, "has no expiration date." In "Letter to You," the speaker informs us that "Nothing can ruin being alive." While in "Whatever It Takes," the speaker adamantly states, "I do whatever it takes // to stay alive while I wait to join you / in an orbit of stars."

Clearly, Stone's speakers avoid sentimentality, bitterness, and misanthropy. These poems in section three instead focus on self-assessment, strength, and growth while simultaneously dealing with the touchstones and reminders of life before her husband's death.

The poems of section four deal with the realization that as a newly minted single person, there remains much to be delighted by and lived. The title of the first poem here, "Living Is All," might stand as a brief statement of the collection's theme. Stone writes, "I tossed your ashes into this bay, / to think of you when I walk here. / And all the while there is delight." A line such as this might be read two ways; first, walking along the bay reminds the speaker of the deceased, which provides delight. Second, the speaker realizes that the act of walking along the bay itself, for its own sake, is delightful.

This speaker appears to be experiencing little, if any, survivor's guilt. She reinforces this in "Spring Again," the title of which suggests growth and renewal, and ends with this line: "I haven't lost the art of flirting."

The book's final section contains eight poems. Stone focuses these on life, not death. They concern possible reconnection in some way with the deceased because, for Stone, no afterlife exists. In "Return Visit," the unnamed "you" is ostensibly the speaker's deceased spouse, whom the speaker watches walk through the door, intent on his cellphone. After some speculation about what a dead person might need a cellphone for, the speaker begins to dance with the vision, clapping her hands and closing her eyes. As might be expected, "When I open them, / you are gone again."

In the final poem, the poet expresses the wish for reunification with her deceased spouse, writing, "We will lie down, the two of us / almost strangers."

Quietly inspiring in both content and craft, Carole Stone's "Limited Editions" is a testament to the indefatigable human spirit. Readers may assume that a collection of poems about a loved one dying, the survivor lonely, sad, and disoriented, would prove a downer. Beneath the grief, however, the life force pulses. We learn reading these poems that focusing only on our losses is a losing endeavor, that it's best to appraise what we have rather than what we don't.

This is an optimistic book, marked by humility, gratitude, and awe. Stone without ambivalence asks us to focus after a loved one's death on that which remains, as in "Egg": "Dear egg, forgive me / for not believing / in an afterlife. You are enough."

Dan Giancola's latest collection of poems is "Near-Ghazals," from BullHead Books. He formerly taught English at Suffolk Community College and lives in Mastic.

Carole Stone is professor emerita of English at Montclair State University. She has a house in Springs.