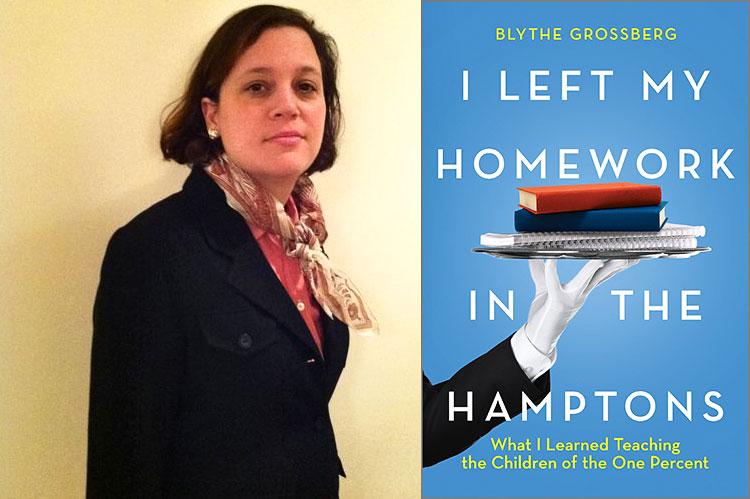

“I Left My Homework in the Hamptons”

Blythe Grossberg

Hanover Square Press, $27.99

Blythe Grossberg's "I Left My Homework in the Hamptons" chronicles her life as a tutor to the offspring of ultra-rich New Yorkers who frequently summer on the South Fork.

Ms. Grossberg is no ordinary tutor: A graduate of Harvard College with a doctorate in psychology from Rutgers University, and the author of eight books on learning differences, she is eminently qualified to describe the challenges faced by students who are born into families in which money, influence, and moxie abound. A classroom teacher of history as well as of writing, and an English tutor, she can also speak authoritatively about the inner workings of the elite private schools that her tutees attend and the interface of the many specialists their parents can afford to hire.

Ms. Grossberg writes in an accessible style that intertwines the stories of several students across the chapters with her insights into the psychological and social processes at work within their families. Compellingly, she shares her personal reflections on growing up in a middle-class milieu — her parents were both lawyers — becoming a parent of a child with autism, and how these experiences shaped her professional perspective on the needs and wants of her clients.

From the outset, I think Ms. Grossberg gets exactly right the damaging impact of endless tutoring on the self-esteem and confidence of young people. Here I speak as someone who grew up in the 1950s with parents who believed that every academic weakness could be remediated with the help of just the right tutor. Although my family was middle class, and hardly part of the upper crust described in this book, no weakness was to be left unchecked to sully a college career, and every B+ begged to be turned into an A with tactful advocacy and the application of additional effort.

Later, as a teacher and teacher educator, I came to understand the value of limited, strategic one-on-one interventions. Like Ms. Grossberg, I was ever mindful of the ways that excessive use of such supports can undermine a student's belief in their ability to master new challenges and manage their own learning.

"I Left My Homework in the Hamptons" paints a picture of high school students who are overprogrammed, pressured to perform at the highest levels at all times, and taught that every interaction is transactional. Parents appear to come in two varieties: the hypervigilant, overbearing, and excessively involved, and those who are distanced, neglectful, hard to reach, and often curiously delinquent in paying their bills. Both kinds of parents possess a similar tool kit to assure their children's success — large donations to the schools they attend, expensive gifts to individual teachers, and aggressive intervention when things don't go their way. Foundational too is the sense of entitlement and the belief that effort always ensures the desired results.

For their part, the schools the children attend are described as bowing to every parental demand and offering little that would invite students to develop perspective on, let alone a critique of, the worlds they inhabit. Most distressing educationally is the description of curriculums that are pitched above and beyond the students, who repeatedly describe school work as irrelevant to their lived experience.

Unfortunately, despite Ms. Grossberg's memoiristic framework, the text often verges on the voyeuristic. For this reader, peering into the lives of wealthy parents awash in money and often unattainable expectations for their children did not prove inherently interesting. And as a New Yorker by birth, and an East Ender for much of my adult life, I was uncomfortable with the constant references to "Park Avenue parents," "children of Fifth Avenue," and the second-home "Hamptons" of the uber-rich. These labels alienate, simplify, and I suspect reflect a certain ambivalence of the writer, who has, after all, spent 15 years of her life embedded in a world of the most economically successful members of society.

In the final chapter, Ms. Grossberg reports that she is leaving New York for Massachusetts, where she grew up. I could not help but wonder if she has not quite come to terms with why she has stayed so long and remained so engaged with families who treat her with less respect than she clearly deserves and who, despite her own middle-class privilege, leave her feeling poor and anxious.

I would have been a happier reader if Ms. Grossberg had pulled back from her exclusive focus on the less than 1 percent and provided more context to complicate her analysis. For example, sociologists have been telling us for years that childhood is rapidly changing across all classes in America. Overprogramming, the loss of self-directed time, and continual adult surveillance are not confined to children of the wealthy.

In New York City, one finds as well different kinds of independent schools, some with more progressive and social justice orientations than those described by Ms. Grossberg. (See "I Learn From Caroline Pratt" in The Star's Jan. 23, 2020, "Guestwords" column.)

Her broad brushstrokes beg a more fine-grained picture of educational choices and the way they reflect different segments of different classes. As a teacher, I also wanted to know about the efforts of the schools in which Ms. Grossberg worked to respond to the real lives of their students. More than that, I wanted to hear the voices of parents and students in a more systematic way that would add depth to the first-person account the book offers.

Ms. Grossberg writes most incisively and movingly when she describes her own struggles as the parent of a child with autism. This experience allows her to identify a common theme shared between her own life and the lives of the rich, an overpowering desire to protect her child from potential harm or failure. This insight helps her to understand, but not necessarily to accept, the lengths to which parents will go to secure safety and success for their children.

Caregivers of people at all ages must confront the central tension between promoting separation and independence and holding others too close on the misguided presumption that we can control their experiences. We are continuously challenged to be present for others and to bear witness to their struggles, but we cannot shield them from the inevitable difficulties that mark all our lives. No one wants another to fail, but in the end the most effective students are those who can learn from their failures and chart their own unique educational journeys.

Jonathan Silin, Ed.D., is the author of "Early Childhood, Aging, and the Life Cycle: Mapping Common Ground." He lives in Amagansett and Toronto and is online at JonathanSilin.com.