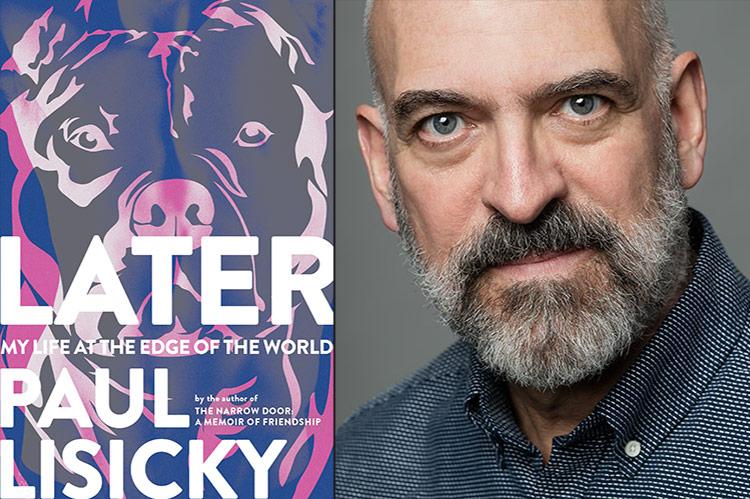

“Later”

Paul Lisicky

Graywolf, $16

In his new memoir, “Later,” Paul Lisicky offers us a beautifully crafted and compelling description of life in Provincetown, Mass., at the height of the AIDS epidemic. His story will be of interest not only to those of us who lived through the epidemic here on the East End, but to anyone who has experienced the rhythms of a resort community close to a major city.

To be sure, Provincetown, with its densely built center and eclectic mix of shops, restaurants, guesthouses, and motels, has always accommodated a more economically and socially diverse population of tourists and semi-permanent residents than East Hampton. At the same time, Mr. Lisicky captures what the two towns have in common: the quickening rhythms of the annual spring awakening, the summer frenzy of temporary pleasure-seekers and permanent residents trying to make a year’s income in a few months’ time, the slowing pace and gorgeous days of fall, and the drawing together and cabin fever that grips us after the December holidays.

Mr. Lisicky arrives in P-town, a short-form name he abjures and to which I acknowledge being securely attached, somewhere in his 30s with a six-month fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in his back pocket, literary ambition on his mind, and a nascent gay identity coursing through his body. When the memoir ends three years later, he has acquired a close circle of personal and professional friends, several serious romantic relationships, and untold manuscript pages. Along the way he has also managed to break the paralyzing bond to his mother that had kept him in Southern Florida.

“Later” is a memoir about becoming a gay person. In Provincetown the author enters an established queer community, one with rich traditions of celebration, care, and creativity. Unfortunately, it is also one that is undergoing the deadly stress of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s. It’s a time of vigils and vicissitudes, especially in a small town where people live physically close together and everyone knows who is well and who is sick. They also know who is thriving despite their H.I.V. status and who is nearing the end of life, who may be counted among the worried well and who has withdrawn from circulation for fear of infection.

I admire Mr. Lisicky’s honesty and determination in the midst of this difficult context to create meaningful if complex intimate relationships, often multiple at any given moment. First we meet Billy, the seductive H.I.V.+ boyfriend who, despite his illness, is always on the prowl. Then we come to know Hollis, the mentor-boyfriend who has another life partner. And finally Noah, the beautiful boyfriend whose impregnable boundaries prevent real intimacy. In the shadow of the epidemic we bear witness to desire realized and thwarted, sex always available and often anguished.

Mr. Lisicky writes his personal story into the public record of the AIDS years, charting his path as it moves into and through a number of overlapping landscapes: the physical geography of Provincetown, the Portuguese fishing community turned gay Mecca; the social landscape of close friends and acquaintances who populate this world; the literary landscape of the Fine Arts Work Center; the background landscape of family, primarily his mother and distant father, who haunt his burgeoning gay life, and above all the landscape of AIDS that dominates the story.

These landscapes come to the foreground and recede within each chapter. Short, subtitled sections, each a paragraph, two or three at most, keep the reader engaged and evoke the author’s youthful energy and episodic quest to become a self-actualized adult. As he tells his mother after having received notice of a second-year fellowship, “I’ve come to know myself here, I can’t go back.”

All of the landscapes are within view at all times. This is not a book to be read for the long narrative arc, intricacies in plot, and storyline. Rather, it’s a text that vividly recreates a particular moment in the past through the eyes of someone who will eventually find a home at the edge of the world.

Writing as a gay man who lived through the epidemic here in East Hampton, I was disquieted by the retrospective coda at the end of “Later.” In 2018 Mr. Lisicky was living alone in Brooklyn, where he’d built an impressive vita that includes a half dozen books, an established career in higher education, and Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts fellowships.

These accomplishments take a back seat, however, to the emotional weight of the coda, which resides in his ongoing search for sex and relationship, a search that takes on new dimensions with access to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), the H.I.V. drug cocktail that allows people to dramatically reduce the odds of contracting AIDS while engaging in unprotected sex.

At the end of “Later,” I was left to wonder how the experience of surviving AIDS in the 1990s had changed Mr. Lisicky and whether it had informed his understanding of how to move forward in life. These questions were prompted by the final pages, which belie the body of the book and the critical role that the queer and writing communities in Provincetown played in enabling Mr. Lisicky to become a successful author.

Yes, the book describes the impact of AIDS on individuals, both sick and well, but it also highlights the way communities responded to the crisis through informal, innovative care networks. And, just as important, it describes a community that allowed Mr. Lisicky to become a fully realized gay man.

Although a decade older and already in a long-term, nurturant relationship when the epidemic struck, like Mr. Lisicky I experienced countless losses in a world that was turned upside down. I was able to channel my anxiety into action, in 1982 co-chairing the first major AIDS fund-raiser at the East Hampton home of the noted New York Times food writer Craig Claiborne and then spending the next decade as a professional AIDS advocate and educator.

Reading “Later,” I was aware yet again of how the opportunity to turn angst into action enabled me to survive and in the process learn much that has served me well in the years that followed.

Haunted by the virus even now, Mr. Lisicky continues to question his right to a future when so many others have been denied theirs. Reflecting on the death of his 91-year-old father, he acknowledges that “In my mind every death will always be an AIDS death; everyone will always die before their time, whether they’re twenty-one or ninety-one.” While I know firsthand that one death can summon up many other losses, I no longer read every loss in the key of AIDS.

Like Mr. Lisicky, I don’t look back on AIDS with nostalgia, but I reluctantly accept that it taught me, albeit out of necessity rather than choice, invaluable lessons about caring for people who are unwell, enduring losses that seem unendurable, and drawing on the strengths to be found in community. I believe that these lessons from the plague years allowed me to go on with a modicum of hopefulness after the difficult decades of the 1980s and ’90s.

Despite the availability of PrEP and the professional successes that mark his career, Mr. Lisicky’s final landscape feels unbearably bleak. Absent the communitarian vision that infused life at the edge of the world, I could not locate the kind of hope that allows us to leave the past in the past and make a future imaginable.

Jonathan Silin was the first director of education at the Long Island Association for AIDS Care. He is the author of “Sex, Death, and the Education of Children: Our Passion for Ignorance in the Age of AIDS” and lives in Amagansett and Toronto.

Paul Lisicky, formerly a part-time resident of Springs, teaches in the M.F.A. program at Rutgers University-Camden.