Oscar Molina, an artist based in Southampton, has produced five substantial bodies of work since he committed to making art full time seven years ago. However, he is probably best known for his "Children of the World," a series that began with paintings and mushroomed into sculptural installations that have appeared not only on the East End at LongHouse Reserve and the Southampton Arts Center, among others, but also at multiple venues in El Salvador and Mexico.

Most of the paintings are densely populated by elongated figures with tiny, barely articulated heads perched atop richly colored bodies without visible limbs. The figures are deployed horizontally across the lower half of the canvas, beneath skies that range from cloudy blue to intense red to dark and starry.

The figures "almost look like drippings," Mr. Molina said during a conversation in his vast studio, which previously belonged to the artist Hal Buckner. "When I went to darker colors and I saw that the moonlight was actually shining over the people and making them into silhouettes, that's when it hit me, I am going to make sculptures. Cement and wire were my trade," he said, alluding to his career in masonry -- but more on that later.

The sculptures are cylindrical, tapering, like the figures in the paintings, to the small heads. Many are more or less of human scale, but some are much taller, and they are always arranged in groups, sometimes as few as three but often in larger clusters. Within each grouping the sizes and postures of the figures vary.

You don't have to know anything about Mr. Molina to appreciate the works in this series, but, once you do, they attain a deeper dimension. He was born in 1971 in a small village in the mountains of Morazan, a state in northeast El Salvador. His family grew and processed sugar cane. "For us it was just enough to sustain our family and the families in the town who worked for us."

When he began to attend school in a nearby town it was a two-hour walk, but "it was a whole new world for me. Then things switched very fast" when, in 1979, civil war broke out between the government, which was backed by the United States, and the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, a coalition of left-wing guerilla groups backed by Cuba and the Soviet Union.

The guerillas were attracted to the Molina family's small town because its location in the mountains afforded a view of 50 miles in all directions. Over the next few years, occupation of the village fluctuated between the guerillas and government soldiers.

On his walks to school, Mr. Molina would encounter roadblocks, where soldiers stopped buses. "I would see people being taken off the buses, and then they just disappeared," he said, adding that at the age of 10 he didn't fully understand what was happening. "I was just trying to learn, to get a better education, to have a better future than farming."

After several months the family moved to the state of La Union, which was near the coast and where his mother's brother gave them a spot of land to build a house. "We went overnight from being farmers to being fishermen," Mr. Molina said.

However, as his brothers became old enough to be recruited by either the guerillas or the government, they began to leave, with the blessing of their parents, who stayed behind. "That was the first time you had that anxiety that you might never see them again. But we were lucky enough to have our parents come to the States 20 years later."

The goal was Long Island, where three of his brothers were living in Shirley and doing landscaping. Mr. Molina left when he was 16 with one of his brothers, first crossing the border into Mexico, where groups of refugees formed and made their way slowly across the desert toward the border with the United States. "A lot of people didn't make it through that journey," he said, adding that others who reached the Rio Grande but didn't know how to swim were left behind.

"Those memories you have of the line of people throughout the desert at night, it was magnificent but scary at the same time." And those memories and that experience are what led to "Children of the World" -- but not until almost 30 years later.

Within a week of his arrival in Shirley, Mr. Molina was granted political asylum and given a Social Security number and a working permit that allowed him to join his brothers doing landscaping. After a few years he switched to a company that also did masonry. He learned that trade so fast that within a year he was leading the entire masonry team.

After five years he started his own company, MOE Southampton. In the meantime he had gone to school to learn English and architecture, working during the day and taking classes at night. He is no longer physically active in MOE, but he is still a partner and the firm has grown to have three divisions.

He also started painting in his free time, "just to get my mind off the business," but when his children were born in 2000 and 2002, he had to figure out how to be a father and still run the company. Later in that decade he started painting again, and in 2013 he had his first exhibition at the Hempstead Library. Those works were well received and wound up in a group show in a museum in El Salvador.

Since 2018, working on his art full time, he has developed four series of paintings in addition to "Children of the World." One of those, "Rain Drops," resembles the "Children" paintings in that the top half is sky, but the bottom half is a strip of paint from which drips cascade. The skies in "Rain Drops" range from day to dusk.

While the "Children" paintings arose in part from his memories of walking into the desert at night and seeing the sky and stars, the "Rain Drops" derive in part from growing up in the mountains where "as a child the force of rain on your face was a magnificent feeling," one that washed away any negativity.

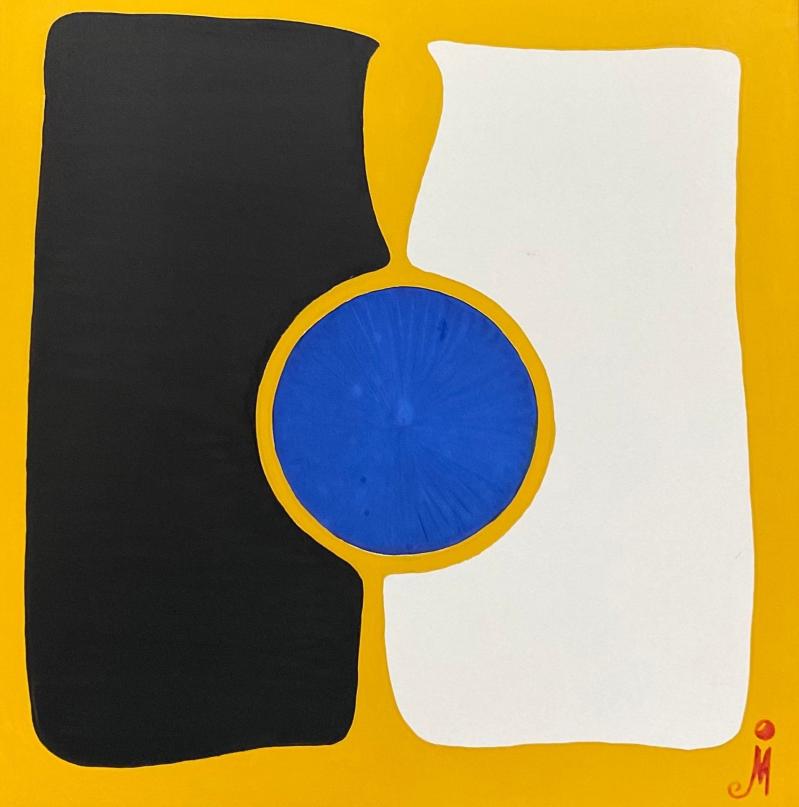

His other series, "Stages of Love," "Tulipanes," and "Values and Principles," are minimalist by comparison. "Stages" paintings consist of one or two semi-human forms, as geometric as they are biomorphic, each painted a single color and placed against a different color background.

Each of the works in "Values and Principles" consists of three shapes, each a different color, placed against a contrasting background. "It's all about a relationship in which your principles might be different from mine but we have to come to a conclusion to work together." That condition is represented by two vertical forms, each a different color, with a circle of a different color between them "that connects the two beings."

The three minimalist series, with their simple shapes and emphasis on color relationships, suggest the work of Ellsworth Kelly, whom he cites as an influence along with Henri Matisse. More related to his "Children" are works by Pablo Picasso, especially "Guernica," which "had a lot of emotional feelings for me because I lived all of that, I saw all of that."

One of the first East End artists whose work he saw was Eric Fischl, whose house he worked on when he was still in the construction industry. "I asked him once what he did to keep himself inspired as a full-time artist. He said sometimes you don't have to paint anything, but you do have to come to the studio to at least smell the paint. I took that very seriously."

Evidence of that commitment is obvious from his studio and the surrounding acreage, the latter populated by several groups of "Children of the World" sculptures and the walls of his high-ceilinged studio, a former barn, lined with large-scale paintings and a new series of works in pencil, pen, and acrylic on canvas, inspired in part by Leonardo da Vinci.

Mr. Molina returns regularly to El Salvador, where his older and youngest brother live. "It's a whole new country," he said. In addition to his sculpture installations there, he has five outdoor installations of "Children of the World" in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, home to his godson.