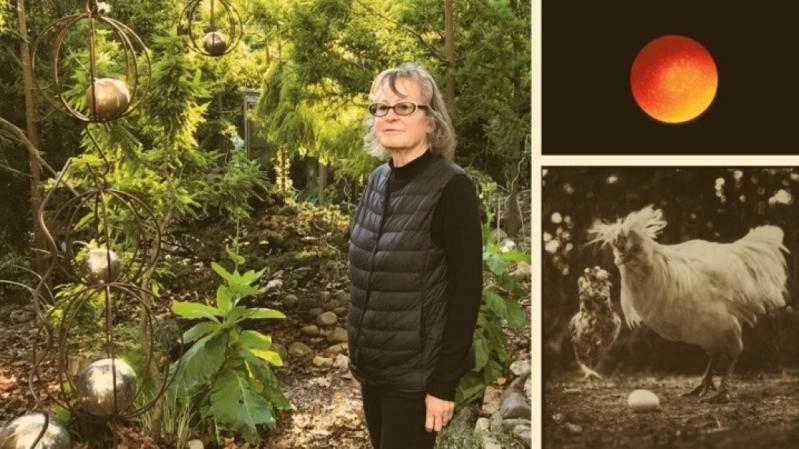

In 2006, a chance meeting changed the artist Hope Sandrow's life. "What happened is, I met the rooster over there," she said, pointing to a fence on the south side of her property in Shinnecock Hills. "There was a hole in the fence, and I told him to follow me home. He did."

It took some time for her to learn it was a Paduan cockerel, an ancient Italian breed of small chickens known for their ornamental tufts and colorful plumage. "He was brilliant. He followed me around and would come through the window in my office and sit with me."

That meeting followed a traumatic illness that almost took her life and left her virtually incapacitated for 10 years. In 1994 a painful tooth led her to a dentist who told her she needed a root canal, then sexually harassed her in the chair before deliberately fracturing the tooth.

The resulting infection caused intense pain, temporary blindness in one eye, neurological impairment, and difficulty walking, yet it resisted diagnosis from a variety of specialists until six years later, when an oral surgeon traced the symptoms to the damaged tooth. The day after he removed it, the pain was gone, but recovery took years.

"When I met the rooster, I was very impressed by his courage to create a new life." With respect to her career as an artist, "I thought I should create my own new life, because I had lost everything."

Before the illness Ms. Sandrow had exhibited widely, including at the pioneering East Village art gallery Gracie Mansion. She had developed relationships with curators, her work had entered the collections of major museums, and at the time of the injury she was running the Artist & Homeless Collective at the Park Avenue Armory Shelter for Homeless Women.

The collective had its genesis in the late 1980s, when AIDS "started hitting very hard and close to me," claiming friends such as Peter Hujar, Jimmy De Sana, and other artists she had exhibited with.

"It made me question my path in life to be an artist, and I wondered what might happen if you lost everything. Would art still be relevant?" A friend was conducting art workshops at the Catherine Street Shelter in Chinatown, "and I decided that was a good place to pose that question."

After several years of working with women and children, she was dismissed when several state senators learned she was helping the residents register to vote and threatened to defund the shelter if she wasn't fired.

Offered other sites by the city's Human Resources Administration, she chose the Park Avenue Armory, which housed women over the age of 45. The collaborative earned non-for-profit status in 1992, the sponsorship of the New York Foundation for the Arts, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Ms. Sandrow enlisted other artists, among them Kiki Smith, John Ahearn, Rigoberto Torres, and Ida Applebroog, to make art in collaboration with women at the shelter. Partnerships with the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and other institutions followed.

The illness put a premature end to her involvement with the collaborative. However, a rebirth of sorts is imminent. The New York Historical Society will present "Art for Change: The Artist & Homeless Collaborative" from Dec. 3 through April 3.

While most of the art from the shelter was sold years ago, the exhibition will feature Ms. Sandrow's copious documentation of the project, including video, photographs, and ephemera, as well as artworks by Ms. Smith, Ms. Applebroog, Ms. Sandrow, and others.

Back to that rooster, whom she named Shinnecock. She and her husband, Ulf Skogsbergh, a photographer, artist, musician, and composer, realized "we had to get him some hens, because he was attacking Ulf, thinking I was Ulf's hen." She found a breeder in the Hudson Valley who sold her several.

The result was not only a flock of Paduans, but "open air studio spacetime," their two-acre property so named because it is an evolving work of art that encompasses the past and present of her Shinnecock Hills property and all living things within it.

"I have tried to turn the landscape into camouflage," she said, with plantings, an overhead web of monofilament, and reflective globes hung from trees to protect her flock from predators. She and her husband built the chicken coops, whose design was based on two-dimensional drawings by the artist Sol LeWitt.

The couple lives and works in two buildings from 1891: a carriage house designed by Stanford White for the American painter William Merritt Chase, and a carriage house/gatehouse designed by the noted architect Grosvenor Atterbury for the nearby Condon estate.

The rumble of the Long Island Rail Road is a reminder for Ms. Sandrow of the development of Shinnecock Hills that followed the railroad to the East End and displaced members of the Shinnecock Indian Nation.

It is clear her art, her daily life, her family background, and the history and politics of where she lives are inseparable. When she followed the rooster across Montauk Highway, she discovered that the property there was for sale. After she began to research the parcel's history, people from the Shinnecock Nation contacted her.

"They said they could use my research and my assistance to help preserve that property, because it was an ancestral burial site." As a result of their combined efforts, in August 2006 the Town of Southampton agreed to use community preservation funds to buy the land and protect it from development.

Ms. Sandrow has continued to work to protect Shinnecock Hills and to preserve the tribe's ancestral lands. Another sacred site, Sugar Loaf, which is across the road from her property, was purchased by Southampton Town in 2021 due to the efforts of tribe members, Ms. Sandrow, and other supporters, including Roger Waters, the co-founder of Pink Floyd.

Born in Philadelphia and raised there, and in Camden and Cherry Hill, New Jersey, Ms. Sandrow's childhood was shadowed by anti-Semitism. "Before we moved to Cherry Hill, I met people who thought I had horns and a tailbone in my skirt."

More traumatic was that a year before she was born, her brother died at the age of 2 weeks, and when she was 5, a sister died soon after childbirth. As a result, "I grew up in a house of tears. I didn't really understand it, and I didn't find out why everybody was crying until I was 12."

She began to draw at the age of 1 or 2, "as soon as I had the coordination to do it. I was in a very traumatic situation at home, and I found art a means to create my own world and also relate to the one I was thrust upon."

A positive legacy was the involvement of her father and grandfather in social causes in their communities, including the N.A.A.C.P., which they joined in the 1950s.

After graduating from the Philadelphia College of Art in 1975, Ms. Sandrow moved to New York City, where she met Mr. Skogsbergh. Among her early works was "Men on the Streets," for which she asked strangers to pose. The images were like film stills, according to Susan Talbott, a curator and former museum director, "depicting action as time lapsed as the men moved across the picture plane."

"Back on the Street" used a similar methodology but drew its subjects from her artist friends, whom she posed against backdrops that recalled their own work. Keith Haring, for example, stood before a graffitied sculpture.

Because art has repeatedly served as a means of recovery for Ms. Sandrow -- from her troubled childhood, being raped in high school by her family's doctor, losing friends to AIDS, and her long, debilitating illness -- it is fitting that her work is included in "Clearing the Air," the current exhibition at the Southampton Arts Center.

Organized by Jay Davis, an artist and curator of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center's Ambulatory Care Arts Program, "Clearing the Air" examines the healing power of the arts. Ms. Sandrow is represented by "Memories Spaces Time" from 1990 to 2000.

That trilogy explored interrelationships of self, art history, and nature. The primary images were of a figure, arms outstretched in a posture common to both rape and religious images of gods reaching out in embrace. She made those images while working in the shelter, where she revealed the history of her rape for the first time. "I realized if I was going to ask them about themselves, I would have to reveal my past."