In the House of Jackson

In the House of Jackson

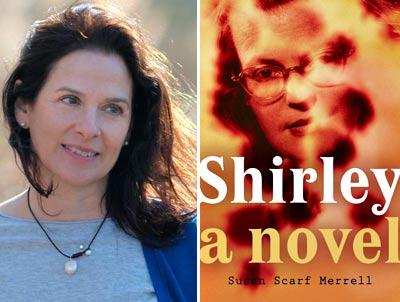

“Shirley: A Novel”

Susan Scarf Merrell

Blue Rider Press, $25.95

Susan Scarf Merrell’s new book, “Shirley: A Novel,” offers varied attractions: elements of the mystery, the period piece, and the psychological novel. Plus, true to title, the book conjures up Shirley Jackson, the captivating American novelist, essayist, and short-story writer known for her chilling works that combine the everyday with the supernatural. Jackson is cast as a central figure in Ms. Merrell’s novel, so those readers who like a brush with fame along with their fiction will find a hook and a footing.

“Shirley” is narrated from the point of view of young, pregnant Rose Nemser, who in the fall of 1964 accompanies her husband, Fred, a graduate student, to begin his teaching career at Bennington College under the mentorship of Stanley Hyman, noted literary critic and husband of Shirley Jackson. Fred and Rose move into Stanley and Shirley’s well-established home and the two couples occupy the big sprawling house over the course of the fall and winter.

The conversation is literary, the dinner parties are many, the cigarette smoke is thick, and the drinks are pouring. Shirley and Stanley have an intensely entwined relationship that runs on a high burn. Shirley is fierce but also psychologically fragile; Stanley is frontal, lusty, dependent on Shirley but also dependent on his appetites. The charged tension created by Stanley’s affairs with students from the college is an atmospheric condition of the marriage and consequently the household.

The specter of infidelity haunts the house, with an element of mystery introduced around the disappearance, in the past, of a Bennington student Shirley claims never to have met. This young woman is Paula Welden, an actual student at Bennington who did in fact disappear; Shirley Jackson’s second novel, “Hangsaman,” a study in dis-ease and the shifting role of reality — internally and in fiction — is widely understood to have been inspired by the case. In a tip of the hat to “Hangsaman,” and as an expression of the referenced weave of her story, Ms. Merrell has named Rose Nemser’s baby (born in the course of the novel) Natalie, the name of the 17-year-old Paula Welden-inspired protagonist of “Hangsaman.” Furthermore, fictional Rose identifies intensely with actual Paula Welden’s disappearance, her “absence from the world.” Watch out here for an intertwining of fantasy and reality that is emblematic of Shirley Jackson’s work, and a tribute to it.

The narrator of “Shirley” hails from a background of edgy loveless poverty, her father a thuggish paid arsonist and her mother a colorless drudge. Rose steps into the warmth and activity of Shirley’s house and is immediately mesmerized by the verve, intelligence, and witchy charm Jackson exudes and commands.

“Shirley’s was the smile of a woman like me, the abandoned and the never-loved; it was the smile of the arrogantly insecure. It was the smile of the mother-to-be who had never been mothered, the smile of the brilliant person in a woman’s body, the beautiful woman in an ugly shell. I loved her immediately, I wanted to be her and take care of her.”

A friendship between young, needy Rose Nemser and middle-aged, fiercely driven Shirley Jackson takes root. The building and collapse of this friendship form the arc of the plot of the novel. The suspense lies in the reader’s anticipation of what volatile Shirley might do to vulnerable Rose. At points in the novel, Ms. Merrell attempts a sort of dream-induced rendering of Shirley Jackson’s note-taking for a novel, as experienced trance-like through Rose.

Ho! This is an ambitious harkening to the reality-bending of Jackson’s “Hangsaman” as well as an expression, Jackson-like, of the slippery hold Rose has on her identity, especially in the face of her great need for recognition, for being “seen.”

“Shirley: A Novel” takes as an epigraph the opening paragraph of “The Haunting of Hill House,” Shirley Jackson’s masterwork of psychological horror, which could be said to share psychic shelf space with Henry James’s “The Turn of the Screw,” champion of the psycho-emotional ghost story. In “The Haunting of Hill House,” Eleanor, a vulnerable and needy woman, joins a group led by an occult scholar who seeks to investigate the psychic phenomena of Hill House, an 80-year-old mansion with a checkered past. Hill House threatens to entrap its inhabitants, and Eleanor is uniquely called to its embrace. The seduction of submission to a sense of belonging, no matter the erasure of self, is defined in “The Haunting of Hill House.” It is a novel that largely defies paraphrase.

References to “Hill House” are liberal in Ms. Merrell’s novel, especially in the passages personifying Shirley and Stanley’s home, its awareness of its occupants, the way the doors stick shut — though in Hill House, the doors will not stay open. Hmm. Parallels between Eleanor of “Hill House” and Rose of “Shirley: A Novel” are apparent. Both are vulnerable, inexperienced, needy, and attractive but lacking self-confidence. Both Rose and Eleanor crave to be seen, crave security, and crave to belong. If Eleanor seeks her sanctuary in horrible Hill House, Rose seeks hers in crazy Shirley.

Meanwhile, in her acknowledgments, Ms. Merrell mentions making use of Shirley Jackson and Stanley Edgar Hyman for the purpose of her story, writing, “My hope is that Shirley and Stanley would be amused by this fictional exercise.” Between the many references, the borrowing, the evocation of Jackson’s vibe, and the drawing of Shirley Jackson and Stanley Edgar Hyman as characters, “Shirley: A Novel” becomes quite the buffet of literary homage.

Looking at the novel at hand, plumbing it for potential and value, a question — the selfish test-question of a gobbling reader — emerges: Does “Shirley: A Novel” inspire the reader to look for more from its author, or inspire the reader to read (or re-read) Shirley Jackson? Or neither? Or both? Both is not impossible, but a feat and a coup. Both is best for everyone, as in, for example, “The Master,” Colm Toibin’s virtuoso-level rendering of the great and complex novelist Henry James as a fictional character. There’s Henry James cropping up again! Wowza, talk about a writer who defies paraphrase.

While the aspect of literary homage is alluring in “Shirley: A Novel,” it also beckons comparison to the work of Shirley Jackson. Intentionally, naturally. And playfully, at times. Dangerously, too. If it were easy to do what Shirley Jackson did, there would be more than one Shirley Jackson, which there is not.

But Susan Scarf Merrell is not practicing fan fiction. Her work is considered, charted, balanced, detailed, and at times complex. If “Shirley: A Novel” is a literary exercise, it is one that flexes muscle well worth developing.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Art of Quitting.” She lives in East Hampton with her husband and two sons.

Susan Scarf Merrell teaches in the M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature at Stony Brook Southampton. She lives in Sag Harbor.