The Gumshoe Is a Gourmand

The Gumshoe Is a Gourmand

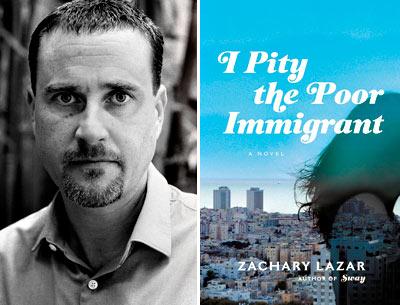

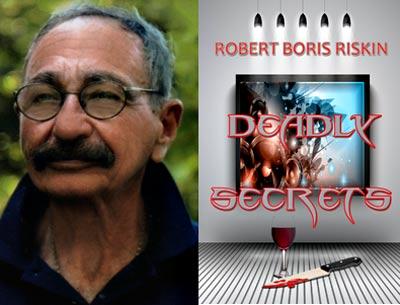

“Deadly Secrets”

Robert Boris Riskin

Black Opal Books, $12.49

If you haven’t already met him in one of Robert Boris Riskin’s previous novels, allow me to introduce you to Jake Wanderman. He is a retired teacher, a one-year widower, and a Shakespeare-quoting amateur sleuth. Though he is unlicensed, Jake is known locally as the Sam Spade of Sag Harbor, where he lives. Originally from Brooklyn, Jake is an avid biker, a terrific cook, and quite the Feinschmecker. One of the consistent pleasures of this novel is vicariously ingesting lots of good food and booze along with Jake.

In “Deadly Secrets,” Mr. Riskin’s third Jake Wanderman mystery, Jake’s childhood best friend, Morty Adler, rediscovers his estranged daughter, Sarajane Relda (Adler spelled backward), whom he hasn’t seen since she was 11 months old, only for her to immediately become a prime suspect in a murder.

The book begins at Sarajane’s art opening at the Valerie Venable gallery in East Hampton. It is typical of a Hamptons summer art opening: glitzy, glammy, and full of beautiful but often snarky people seeing and being seen. Mr. Riskin wastes little time getting to the murder, which happens almost immediately; however, he can’t help but stop to poke some fun at the Hamptons summer scene along the way.

The “art” (Jake’s quotes) is an installation consisting of a living room, bedroom, and kitchen, “uninteresting, the furnishings right out of a 1950 House Beautiful magazine.” Jake confides, “What made this a work of art, I didn’t know, but maybe that was the point.” As he is wondering, a young server offers him “tuna ceviche with edamame puree on a wonton chip,” along with a glass of champagne. The event is catered by a celebrity chef named Tony Oakhurst, who, aside from being the victim-to-be, is something of a bastard, a womanizer, and a coke addict.

Jake leaves the reception, goes home, has a drink (his preferred quaff, Luksusowa Polish vodka), and is awakened at 5 a.m. by a call from Morty telling him that Sarajane (known as SJ) and her girlfriend Margo have been picked up by the East Hampton police and are being held at the police station. Jake drives over to pick Morty up, and on the way to the station Morty tells him the story of this until-now-unknown daughter and her mother.

“We just couldn’t get along. Marybeth [Sarajane’s mother] was a kid who never had to do anything. She didn’t know how to cook or care for the baby.” Eventually Morty decided to leave, and though he continued to financially support the baby, the mother and her family never allowed him to see his daughter again.

When they arrive at the station, Jake sees the lovely redheaded Detective Sienna Nolan, a Suffolk County homicide cop whom he already knows from a previous investigation. They had a “one-time thing” in Mr. Riskin’s “Deadly Bones.” It left Jake wanting more, but despite Jake’s persistent advances, Sienna is standoffish and resistant to reigniting anything. Jake learns from Sienna that in the middle of the night, Tony Oakhurst, the celebrity chef, had been stabbed to death at the art installation with one of his own knives. “It seemed as if he were trying to crawl away from his attacker. The handle of a knife was clearly visible in his back.”

Because Sarajane and Margo are the ones who found the body, they have been brought in for questioning. They claim that they were there in the middle of the night just to see how the 24-hour exhibit was doing. What Sarajane does not tell the police, but does tell Jake and Morty, is that many years ago, when they were students together in Paris, Oakhurst had raped her. We find out that Sarajane’s fingerprints are on the knife and there are “fibers from the victim on Relda’s dress.” Things are not looking good for Morty’s daughter. Jake, of course, wants to help his friend out by clearing Sarajane.

Fearful that the rape story will come out and give the police a plausible motive, making her a prime suspect, Sarajane and Margo flee East Hampton and head back to Paris. The plot becomes increasingly complicated from this point. Turns out that Oakhurst was in possession of $150,000 worth of cocaine when he was stabbed. It got pinched. By Margo. The cops don’t know about it at all, but a very large man with a completely shaved head had apparently come to the Huntting Inn looking for it before SJ and Margo fled back to Europe.

And shortly there is a second victim. “A girl was found murdered last night. It seems this guy Oakhurst had been subletting a place on East Sixty-Seventh Street. Someone slugged the doorman, went up to his apartment, got in, and murdered the girl.” She was Tony’s current squeeze.

There is some lovely writing in “Deadly Secrets,” like this description of grief returning upon Jake’s return from London:

“The instant I walked into my house, [his dead wife] Rosalind’s presence enveloped me. I let my carry-on bag drop to the floor and stood there, immobilized. Tears came into my eyes. Rosalind’s death had turned me into stone for a long time. There were periods when memories of her were so powerful they consumed me. I couldn’t resist them. In fact I didn’t want to resist. With time and effort, I’d managed to return to a semblance of a human being. And I wanted to stay there. But there were ineluctable forces that continued to lurk. Depression was one. Like a cancer in remission, you believed it had been wiped out, that all the cells had been bombarded or chemo’ed and were cleaned out of your blood. And then one day you’re surprised to notice a little lump on your side that had never been there before, and you go to the doctor and learn that what you thought was gone had returned.”

For me, “Deadly Secrets” is not without its minor missteps. At one point, in Paris on a dark street, Jake is assaulted by a knife-wielding assailant clearly intent not on robbing him, but killing him. He manages to kick the baddie in the nuts, knock him to the ground, and even makes him drop the knife. But then, instead of pressing his advantage, interrogating the assailant, and finding out who sent him (or, for that matter, discovering if he is, in fact, the person who killed Oakhurst, also with a knife), Jake simply runs off.

At another point, Jake gets possession of Oakhurst’s valuable bag of cocaine, which he knows some very tough people are looking for. He decides to flush it all down the toilet instead of holding on to it for later. You just know that is going to cause trouble for Jake somewhere down the line.

Quibbles aside, however, for Hamptons readers, as was the case with Mr. Riskin’s previous two novels, “Deadly Secrets” is full of fun, and is as East End-local as a novel can be. Jake travels to Paris and London in hot pursuit of the killer or killers, but the many scenes set in the Hamptons are the greatest pleasure to read. It is a delight to recognize venues from the Palm, Goldberg’s Bagels, and Rowdy Hall to the duck pond, Newtown Lane, and Wiborg’s Beach. In his quest for the killer, and in his romantic pursuit of Sienna, Jake wanders to many places that will be happily familiar to readers of The Star.

I don’t want to give away the ending, but suffice it to say that Mr. Riskin does his very best not to violate Raymond Chandler’s dictum: “The solution, once revealed, must seem to have been inevitable. At least half of all the mystery novels published violate this law.”

Michael Z. Jody, a regular book reviewer for The Star, is a psychotherapist and couples counselor with offices in Amagansett and Manhattan.

Robert Boris Riskin lives in Sag Harbor.