Court Cases That Mattered

“The Mother Court”

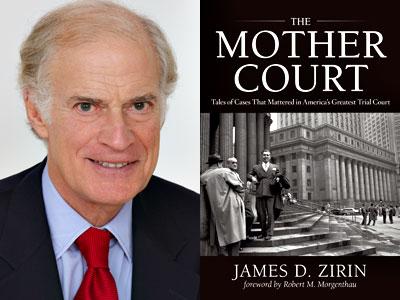

James D. Zirin

American Bar Association, $29.95

What do bishops, celebrities, politicians, generals, professional athletes, Holocaust victims, drug addicts, and just plain folks have in common? All of them have chosen the memoir as the literary vehicle to lay bare their inner lives.

The craze began in 371 A.D., when St. Augustine, a Patristic Catholic and a bishop in his church, haunted by a boyhood misdeed — the theft of two pears from a neighbor’s tree — sought expiation by confessing that sin and others in a memoir aptly titled “Confessions.”

This summer, hundreds of East Hampton residents lined Main Street to gain admission to BookHampton, where on a hot Saturday afternoon, Hillary Clinton read from and signed her memoir “Hard Choices.” (The price of admission: the purchase of the book.)

A memoir bears certain similarities to an autobiography. In both, the narrators are the authors and the tale is told from their point of view. The two have an important difference, however. An autobiography is a documented chronicle of the author’s life; a memoir is a slice of life requiring no more documentation than a good memory. Because of the lesser demands on the memoirist, what started as a trickle 2,000 years ago has evolved into a tsunami.

The reaction of critics and readers to memoirs has not always been favorable. They have accused memoirists of having inflated egos, being afflicted with narcissism, and seeking to place a halo over their sinning heads. Sigmund Freud declined to write his, contending that to do so he would have to offend friends and enemies or shield them through acts of mendacity.

James Frey, in his memoir “A Million Little Pieces,” circumvented Freud’s dictum. Mr. Frey, a drug addict and alcoholic at age 23, wrote about his rehabilitation. In lieu of indiscretions and mendacity, he invented events and circumstances. His book soared to the top of The New York Times nonfiction best-seller list. When the fraud was revealed, sales increased (and The Times, inexplicably, continued to list the book as nonfiction).

James D. Zirin’s “The Mother Court: Tales of Cases That Mattered in America’s Greatest Trial Court,” is a memoir that avoids ego-tooting, narcissism, and mendacity. Mr. Zirin, a top-notch trial lawyer, focuses on the litigation skills of his contemporaries, not on his own. In a chapter probably unprecedented in the annals of legal writing, he rates his favorite judges, not only by naming them, but by showing why they deserve commendation. In another stark departure, he excoriates other judges by describing their lapses in judicial temperament, intelligence, or both.

Like judges, there are good lawyers and bad ones. An effective lawyer will make his case attractive and understandable to the court or jury. Mr. Zirin is a good lawyer and a good writer. He guides us through a thicket of nine troublesome areas that, over the past 60 years, confronted the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, which he calls “The Mother Court.” Hence the title.

He first discusses the espionage case against Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, presided over by Judge Irving Kaufman, criticizing Judge Kaufman’s conduct of the Rosenbergs’ trial and the death sentence he imposed upon them. Subsequently discovered evidence has revealed that Ethel was innocent, and that the information passed by Julius to the Soviets was innocuous. Mr. Zirin points out the obvious: Once the Rosenbergs were electrocuted, there was no way to correct the errors.

In discussing pornography, another of the troublesome issues, he turns a spotlight on the banning of James Joyce’s novel “Ulysses.” The story is told in a series of anecdotes and quotations from the decision upholding the right of the publisher to distribute the book.

(One small quibble: When Bloom peeps at Gerty’s bloomers, she is on Sandymount Beach, not, as Mr. Zirin says, on the “street.” A small distraction from a fine exposition of the serious issues surrounding censorship.)

The author provides an insider’s view of the epic battle between the Nixon administration and The New York Times over the publication of the Pentagon Papers. Mr. Zirin, a confidant of the trial judge, Murray Gurfein, calls his decision in favor of The Times an exemplar of the blindness of justice. Judge Gurfein was appointed to the federal bench by Nixon, and his first case was that of the Pentagon Papers. It was unlikely that a judge newly appointed by a sitting president would deny the injunction sought by the government. If that assessment were made, though, it was done without considering Judge Gurfein’s intellectual independence. He scrutinized the Pentagon Papers, concluded national security issues were not involved, and denied the injunction.

Mr. Zirin discusses four libel cases, two of which involved actions by generals against the media. By coincidence, both cases were tried at the same time in the Southern District.

My favorite chapter discusses the campaign against Roy Cohn, who was counsel to Senator Joe McCarthy in the infamous Army-McCarthy hearings of the early 1950s. I knew Cohn had been prosecuted for federal crimes, but I did not know that during a brief period in the 1960s, he was indicted three times and acquitted three times. Mr. Zirin, an assistant U.S. attorney at the time, relates his office’s defeats and Cohn’s triumphs with disarming fairness, crediting Cohn for effective but devious legal stratagems.

Other cases covered include prosecutions against corrupt public officials, the Mafia, accountants, and terrorists.

Although the author purports to pay homage to his eponymous hero, the court, what emerges is his own passion for the law. The book is a love story; Mr. Zirin’s love of the law.

I was a trial lawyer for 43 years during most of the time covered in this book. I referred to the “Mother Court” as the Southern District. I heard the court’s other name for the first time when I picked up this book. Although we called the court by different names, all of the judges and most of the lawyers referred to by Mr. Zirin, I also knew. He got them right.

I have been retired for almost 15 years. For most of those years, I have not thought about the Southern District. Mr. Zirin escorted me back through time, for which I thank him. I enjoyed his book. So will lawyers and laymen, especially those who lived through the turbulent times of the latter half of the 20th century.

James D. Zirin has a house in East Hampton. He is the host of the cable TV show “Conversations in the Digital Age.” This is his first book.

Sidney B. Silverman, a resident of Amagansett, has written his own memoirs and four novels. The most recent, “The Wall, the Mount, and the Mystery of the Red Heifer,” will soon be published.