Your Blather Here: The Contest

Your Blather Here: The Contest

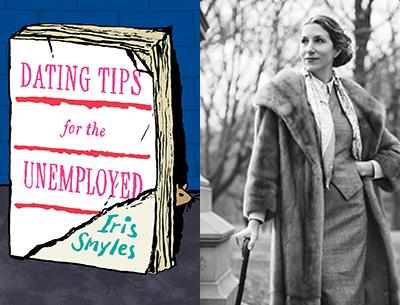

When it came time for Iris Smyles to meet with the publicity people at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt to “do the usual thing of getting blurbs,” as she put it over the weekend, for her book “Dating Tips for the Unemployed,” which came out this week, the ass-kissing and self-promotion could’ve sent her soul fleeing her body like a shirt ripped from a hanger. Instead, pausing in her consumption of some takeout, she noticed a promotion from the online company that had delivered it, a contest, really — your testimonial here, or something like.

The National Blurb Contest was born.

And last week it ended. We have a winner. And is he ever a winner: Alec Baldwin. Must he be good at everything?

“I didn’t read this book and I didn’t have to,” he begins, going on to compare the author’s name to corporate logos guaranteed to tease your pleasure center — Coca-Cola, Fritos, Entenmann’s. In other words, “what’s inside,” he writes, “is so yummy.”

An asterisked note follows indicating that he “was paid for this endorsement,” and may he enjoy his gift bag, trophy, and free copy of the book he didn’t read, as such were the spoils handed out at the black-tie awards ceremony, or rather “book launch breakfast gala,” held midweek last week, from 6 to 9 in the a.m. at the Econo Lodge on West 47th Street in Manhattan, “in the lobby,” the invitation deadpanned, if invitations could deadpan, “next to the ice machine.”

“It took them months to agree,” Ms. Smyles said of Econo Lodge’s hosting of the, uh, close-quarters awards ceremony. “They thought we were pranking them.”

On the contrary, she has fond memories of staying at Econo Lodges on trips to Florida as a kid. (She grew up in Dix Hills — “a pit, but a nice pit, a well-furnished pit.”) “My dad would delight in the free juice in those lobbies.”

“It was surprising — I was thinking and hoping no one would come, it would be just me and my agent, and I’d never take my dress off,” like Charles Dickens’s spurned Miss Havisham, only here, rather than sparked by a fireplace, the author imagined her Vegas showgirl getup complete with turban bursting into flames as she walked by a drycleaners.

But show up they did, some 200 strong, and you could count in that number a runner-up who showed up, sure, but also didn’t: Scott Stossel of The Atlantic magazine, who flew in from Washington, D.C., but subsequently never made it downstairs from his hotel room. Sleeping, presumably.

The other runners-up were William Souder, the author of the quite serious “Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of ‘The Birds of America,’ ” and John Stintzi, a poet studying in Stony Brook Southampton’s M.F.A. program who, bless him, limited his entry to “Hi Mom.”

Mission accomplished. Blurb industry sent up. One day may someone look back on it and wonder how it ever came to pass that so much time, effort, and space were spent on something of such little consequence.