Julian and Barbara Neski’s groundbreaking Chalif House (1964) at 28 Terbell Lane, East Hampton, has recently come on the market for $11 million-plus. The house is historically important in many ways, but given the temperament of the times, the value of a one-acre plot, and its central location — at the very heart of the village’s estate section — there’s a likelihood that it will be torn down.

Chalif was the first project to bring the Neski partnership international acclaim and was published extensively at the time, in both design journals and books, often singled out as an example of how modernism could be made to harmonize with a historic context. In 1970, the Chalif House was exhibited at the Expo 70 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan, as an example of the best in modern American design. It predates (by a year) the famously sculptural house that Charles Gwathmey designed for his parents in Amagansett, and set the bar for other experimental houses to come, especially on eastern Long Island.

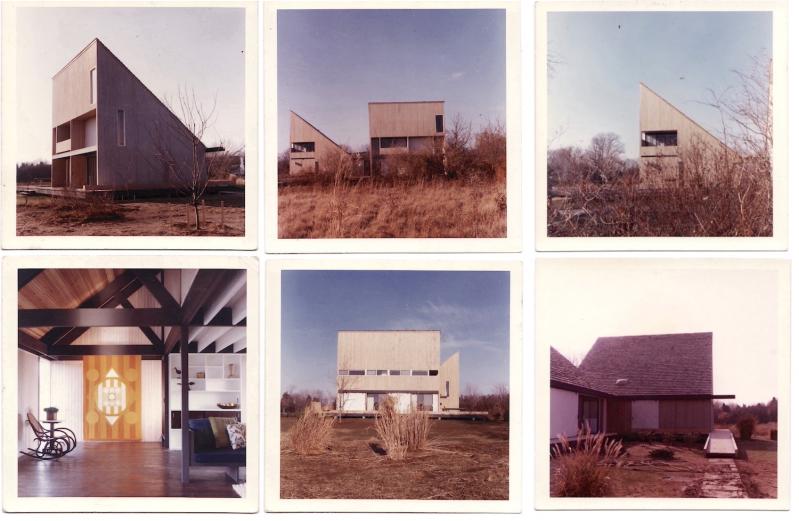

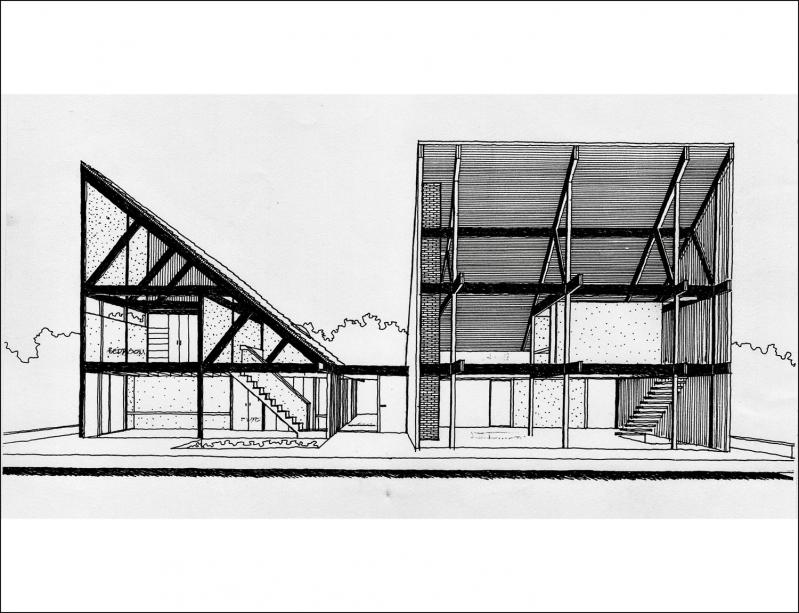

Designed for Seymour Chalif, a New York attorney, and his wife, Ronnie, an artist, the original version of the house was conceived as a finely balanced configuration simple, spare, and elegantly detailed, combining the influences of Japanese temples, New England saltboxes, and the geometric modernism of Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer. Two steeply sloping roofs cut sharply against the sky, opening and closing as one walked the periphery of the property. Roofs were clad with rough-cut cedar shakes, while exterior walls were made of vertical cypress siding, bleached a light, driftwood gray. Barn-like shutters hung from metal tracks and could be pulled across the larger swaths of glass to close the house at night and/or protect it from inclement weather.

The small husband-wife team of Neski Associates would go on to design other weekend retreats each one different from the last and became known for a subtly refined interpretation of the modernist aesthetic. They knew how to produce architectural poetry, and the Hamptons became their preferred testing ground. They designed more than 25 weekend utopias here, including such classics as the controversial Cates House (Amagansett, 1969) for a menage a trois of Sullivanian psychotherapists; the Le Corbusier-inspired Sabel House (Bridgehampton, 1970); and the frenetically interwoven geometries of the Kaplan House (Amagansett, 1971).

At first glance, the two wedge-shaped pavilions of the Chalif House appeared equal in size, turning away from one another at a right angle and connected by a low, glassed-in breezeway. (In fact, the northernmost structure was almost twice the size of the southern one.) Interior spaces were open and breezy. Structural timber posts, beams, and triangulated trusses were left exposed but stained black, in contrast to the pale plaster partitions and built-in cabinetry, also designed by the Neskis.

The architects tried to acknowledge the village context of privet, old barns, and shingled cottages without resorting to imitation or pseudo-historicism. “We wanted to match the height of the surrounding mansions without the expense,” said Barbara Neski, whom I interviewed in 1991, soon after she and Julian had been invited by new owners to design an addition to their 1964 original. The tops of the shed-roofed forms met the height of neighboring houses, while the cedar shakes and barn-like doors echoed the feeling of a local vernacular. To some, the sloping roofs may have seemed less radical than the flat-roofed cubes of Peter Blake and Gordon Bunshaft, but the project remained a thoroughly modernist affair.

From afar, the twin pavilions read as discrete objects, abstract and minimal, evoking a sense of detached neutrality that was further emphasized by the wooden deck, which served as a sculptural plinth to support the opposing forms and elevate them off the ground. Two sunken gardens helped to break the monotony of the wraparound decking, while hyper-elongated rain gutters extended the architectural lines into the surrounding landscape. There were no conventional railings or steps to break the flow, only a gradually sloping ramp that provided entry.

The outer skin of cypress siding appeared taut, punctured here and there by a series of different-sized openings. Fenestration on the north and south elevations was broken up in a Mondrianesque grid of vertical and horizontal elements, interspersed with recessed ledges, panels of glass, exposed beams, a Juliet balcony, deeply set voids, and narrow setbacks.

When completed in 1964, the Chalif House struck a chord. It received almost as much media coverage as its principal rival, the Gwathmey House in Amagansett. The New York Times Magazine called it a “House Divided;” Architectural Forum described it as a “Saltbox Split in Two;” House Beautiful called it a “Novel Slant on a Seaside House;” while Look hailed it as nothing less than a “20th Century Landmark.” It became a popular model during the second-home craze of the 1960s. Soon, poorly executed knockoffs were appearing down the length of Long Island and as far away as the Jersey Shore.

I first wrote about Chalif in 1991 when new owners, Fred and Robin Seegal, decided to expand the house while honoring its existing layout. Instead of hiring a new architect, they reached out to the original authors, and while the Neskis were only too willing to revisit one of their classic designs — they knew the house well, almost too well it turned out to be one of the most challenging commissions they’d ever accepted. Every part of the original bipartite design was perfectly calibrated. To remove or shift a single element could disrupt the overall arrangement. “We really understood the house, and it had strong rules that had to be obeyed,” said Barbara Neski. “It was a real bare-bones expression, and proportion-wise we struggled with every inch.”

Instead of enlarging what was already there, their solution was to add a third element, another wedge-shaped pavilion, that would complement the first two but stand on its own as an autonomous element. This new component may have not been as resolved as the earlier structures, but it introduced a more enveloping and protected sense of scale, featuring a different roof treatment, larger windows, and pickled white floors, as well as a large bedroom suite, a Jacuzzi, a two-car garage and a guest bedroom.

It is to be hoped that some enlightened shopper, with $12 million to spare and a penchant for vintage modern, will come along in the next few weeks, step up, and restore the Chalif House to its original condition. There have been any number of early-modern houses demolished in the past 20 years including important examples by Peter Blake, Norman Jaffe, George Nelson, Gordon Bunshaft, and Andrew Geller and they are losses to the cultural fabric of the town that can never be replaced. Considering its pedigree, the Chalif House one certainly seems worth fighting for.

The New York-based architect Andrew Pollock, who patiently restored and expanded the Neskis’ Cates House in Amagansett, believes there’s a way to preserve Chalif without seeking any zoning variances. According to Pollock, the interiors of the two original pavilions could be opened up and consolidated with a larger kitchen and a larger, double-height dining room, with a bedroom above the kitchen. The less successful addition from the late-’80s could be removed altogether and be replaced with a sympathetic 2,324-square-foot addition connected by a glass breezeway (as was done with the Cates restoration).

“Since only 5,472 square feet can be built on the one-acre lot, this would be the same size house as any project planned for the site, while saving this masterpiece of mid-century design,” said Mr. Pollock.

This does not have to be an impossible dream.

Julian Neski died in 2004 at the age of 76.

Barbara Neski died earlier this year, on March 23, at the age of 97.