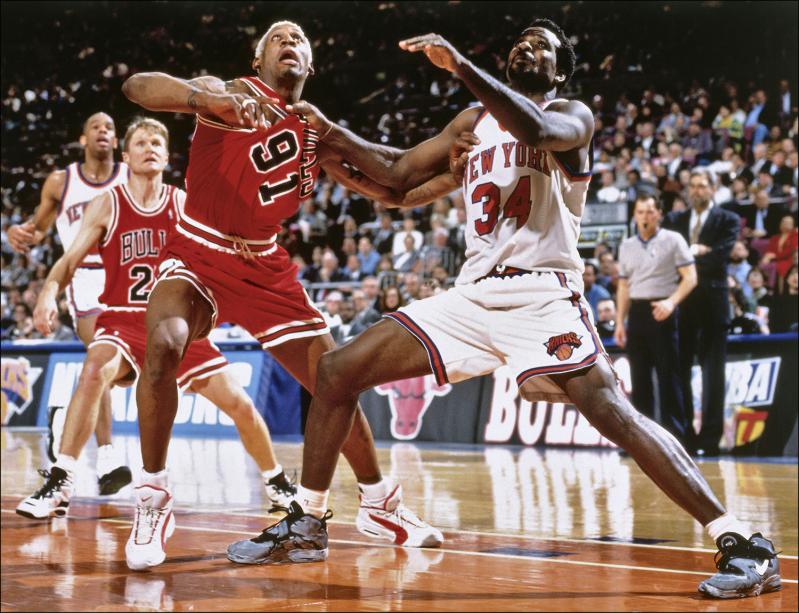

The National Basketball Association must be proud not only of its extraordinary players, but also of Nat Butler, a Montauk native who has taken extraordinary photos of them on and off the court over the years — as is abundantly evident in his recently published book, “Courtside: 40 Years of NBA Photography,” a book in which Patrick Ewing wrote one of the forewords, Spike Lee, with whom the photographer did a signing recently at the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, an afterword, and the strobe-lit players themselves many of the captions.

And, at 62, he’s still at courtside, and enjoying it, Butler said during a conversation at The Star the other day.

He could have been a fisherman, like his late father, William, who captained a Montauk party boat, the Lazy Bones, and wouldn’t have minded, but sports photography exerted a stronger pull. The timing, moreover, was great.

“I’ve always joked that I was in the class of 1984, somewhere near the bottom, Michael Jordan being the first pick that year.”

“Yeah, I’ve always loved basketball. I remember as a freshman at East Hampton High School looking up to those guys . . . Howard Wood, Ed Petrie Jr., Kenny Carter, and Scott Rubenstein . . . who played on that 1977 state-championship team. They set the table . . . they set a great example for us.”

It was, he said, “all about sports in high school. I have so many fond memories. Yes, you’re right, there was an unwritten rule that if you wanted to play basketball for Coach Petrie, you’d better run cross-country in the fall. Actually, I enjoyed that because I did track in the spring. . . . I loved baseball too. When I was a freshman, I wanted to play it in the spring, but my older brother, Rhett, was the captain of the track team, and he told me, ‘You’ll do track.’ They needed bodies — otherwise they’d have to forfeit some meets.”

Mike Burns, whom he said he loved, “made it a lot of fun — we worked hard, but he made it a lot of fun.”

When shown a photo of him either long-jumping or triple-jumping in 1980, his senior year at East Hampton High, with Coach Burns urging him on in the background, Butler forwarded a cellphone photo to one of his sons, reminding him that his father had been young once too.

He got his first camera “maybe when I was a junior in high school. I took photos of sunrises in Montauk, fishing, things like that, and I sort of gravitated to it. Every Thursday, I’d look through Sports Illustrated at all the photos. . . . Then I got to meet Walter Iooss, who lives in Montauk. He was a huge influence — not just on me, but on an entire generation of photographers. . . . The St. John’s basketball team was really good when I went there. I was nowhere near good enough to play, but I became friends with guys like Chris Mullin, Mark Jackson, and Walter Berry. . . . The Big East in the early ’80s had the best basketball in the country. So, I started taking pictures for the school newspaper. . . .”

He began taking them from the baseline at Madison Square Garden, where St. John’s played its home games, assisting such legendary Sports Illustrated photographers as Manny Millan and Heinz Kluetmeier.

“Sports Illustrated and Life magazine and People magazine shared the same equipment and photo lab, which was in the Time-Life building then. You might bump into Alfred Eisenstaedt there . . . it was quite a privilege to be in the right place at the right time and I learned so much from all of them. Shooting film was much more technical then, the equipment is much better now. Now, I press a button and images appear in Secaucus, where the N.B.A. headquarters is, in two seconds. But having that background was invaluable. I’ve got a lot of memories,” he said with a smile, “of traveling with film and mixing chemicals in a hotel room, and bringing clothes pins and hanging up the film in the shower . . . a lot of very late nights.”

“It’s kind of crazy in retrospect. After college I was trying to decide where to go . . . I was toying with the idea of going to law school, but I wanted to give photography a shot. I had some friends who were associated with the N.B.A., and I needed a job. A couple of years previously, the N.B.A. had started creating a video archive, so I pitched the commissioner [David Stern] on the idea of creating an N.B.A. library of still images, as well. He appreciated the history of the game and the value of documenting its growth. I was at ground zero when it came to building an N.B.A. archive. Again, it was perfect timing — I’d spend the day reaching out to A.P. and U.P.I., which would submit images for the library, and at night I’d go to the Garden to create new content. I was 19 or 20 years old . . . it was quite a time.”

“The N.B.A. was making a big push internationally then, so there was a big demand for these images. We’d shoot and send them all over the world — to Australia, France, Spain . . . Germany was a huge market. It all culminated in 1992 with the Dream Team, one of my most memorable experiences. We were together six or seven weeks at the Barcelona Olympics. That’s where you got a sense of the worldwide popularity of basketball. That team was like a Who’s Who of the N.B.A., with Michael, Magic, Bird, Charles Barkley, Mullin, Patrick Ewing . . . they were swarmed wherever they went. I guess it was like being with the Beatles.”

“Most of them are good guys — very thankfully,” Butler said, when asked if he’d ever met a pro basketball player he didn’t like. “I’ve always been respectful of their space. You get a feel for it — when to get your camera out and when not to. As a fan, you know that people love the behind-the-scenes moments . . . of Michael sitting next to Magic on a bus ride, for example, and laughing . . . those moments when everyone is a kid, to be honest. But it’s equally important to know when to give them their privacy.”

Asked how he got to be so good at what he does, Butler said, “It’s a question I get asked a lot. It’s like any other career — you have to work at it, and take advantage of it when the opportunity arises. You don’t go to Harvard Law School and argue a case in front of the Supreme Court right off the bat. It’s the same with sports photography: You don’t start off with the N.B.A. finals or the Super Bowl, you start off shooting fifth-grade basketball and work at your craft. You have to work at it.”

He’s always been a one-click photographer — after having spent four to five hours in cavernous arenas setting strobe lights up high before attending to the action.

And then comes “the mental test that I enjoy . . . do I get Scottie Pippen driving down the lane, or do I wait for Michael to shoot? I’m the exact opposite of the ‘spray and pray’ photographers who take 15 to 20 shots a second and hope that something comes out. One click. I like the challenge and discipline of that — that’s what I do. . . . There’s a lot of preparation. And a little luck never hurts.”

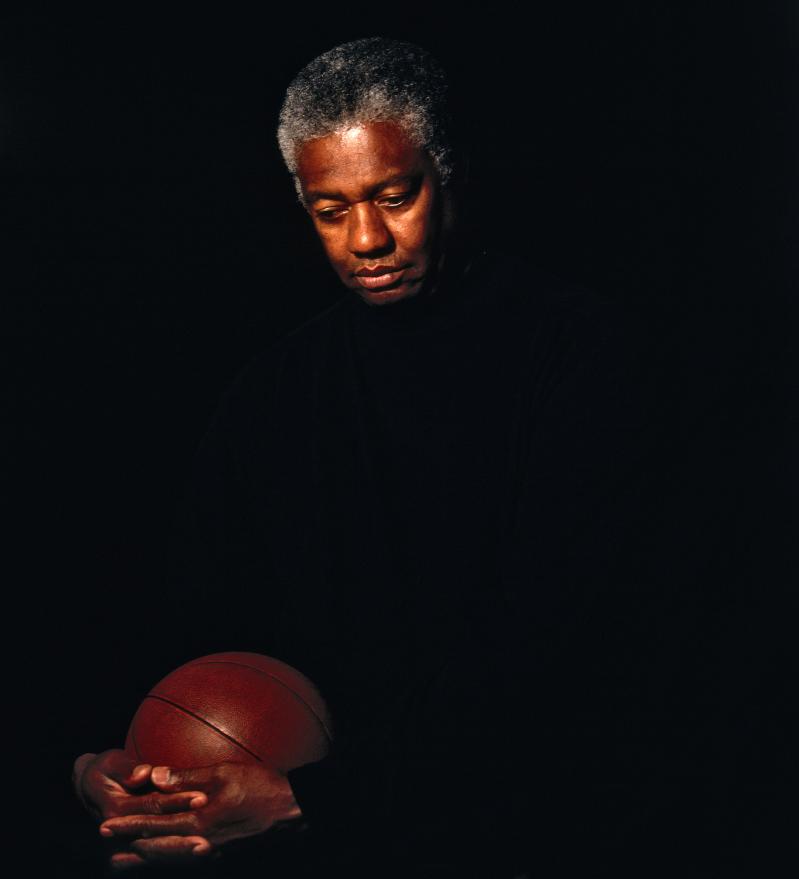

Leafing through “Courtside” after having been told that one of this writer’s favorites was of a pensive Oscar Robertson, his downturned face barely limned in the dark, Butler said it was a favorite of his too, taken after Robertson, then “in his 60s or 70s,” had finished a lunchtime shoot-around at a Cincinnati Y.M.C.A. Leafing further, he said, “That’s Magic making the game-winning shot in game four of the Lakers-Celtics N.B.A. finals. I remember running back to the hotel to develop the film, to see if I got it. He said it was one of his favorite shots . . . that meant a lot to me.”

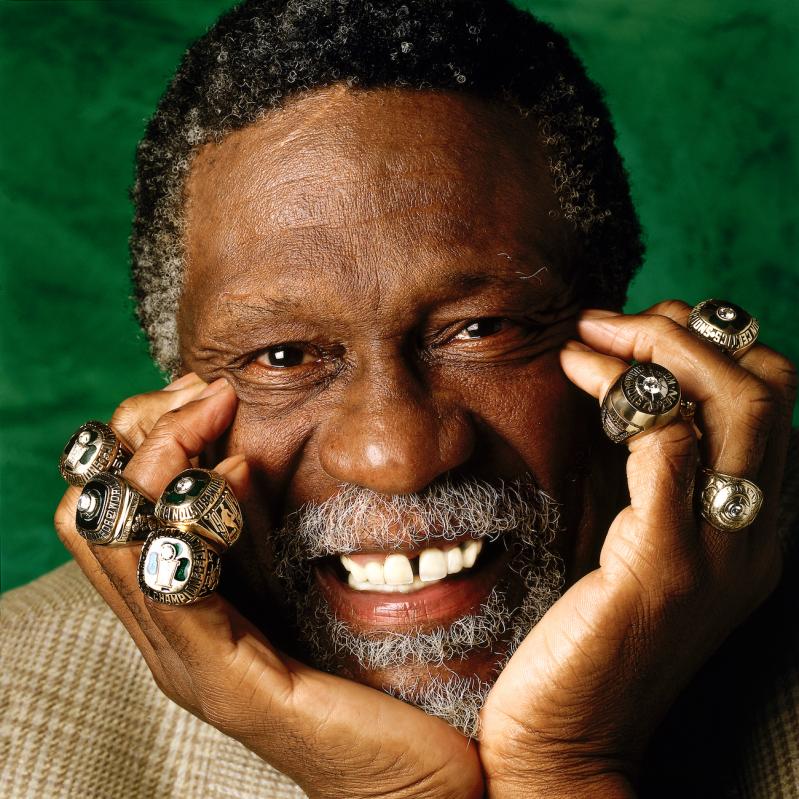

“There are just a lot of memories, you know. . . . I took that shot of the 50 greatest players of all time in 1996. It was a little stressful taking a portrait of 50 to 60 people in five minutes, a little intimidating . . . and then, 25 years later, a shot of the 75 greatest of all time. It was quite a privilege for me personally. At the end of the day, I’m a fan, you know. A lot of these guys have passed. . . . Looking back, I think what was cool for me in doing the book was getting the players basically to do the captions.”

“Now, it’s a little crazy,” he added, “because a lot of the young guys know of me. I don’t say this in a bragging way, but the first time I met Kobe Bryant, he came up to me and said, ‘Oh, you’re Nathaniel Butler,’ and gave me a big hug. ‘Do I owe you money?’ I asked him. And then he explained. He had grown up in Italy where his dad played, and he had all the Michael Jordan posters, and, because he was so attentive to every detail — he was meticulous in studying his craft — he’d look for the photographers’ names. I thought only my mom and I cared about that.”

Many of the N.B.A.’s highly paid players did good works, he said. “I can honestly say almost every player has a foundation. LeBron does so many things . . . he has a high school that he fully funds, and he pays for every graduating senior’s college. A lot of these guys give back because they know where they came from.”

Similarly, he was reminded that “a lot of people opened doors for me. So, I want to pay it forward a little,” Butler said as he signed a book for a fan of his — one of his interviewer’s grandsons.

“I like encouraging younger people,” he said in parting, “because people did that for me.”