There’s been a lot of controversy lately about Confederate memorials, whether in the form of massive statues in the centers of Southern towns or military bases named after Confederate generals.

The voices have ranged from defenders who say that figures like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis were honorable men who fought for what they believed in, and detractors who say that the takedown shouldn’t stop at Confederates but should be broadened to include all racists of whatever era: Washington and Jefferson, who owned slaves; Andrew Jackson, who dispossessed whole tribes of Native Americans; Theodore Roosevelt, who was at the forefront of “big stick” American imperialism, or Woodrow Wilson, who championed racist polices both at Princeton University and in Washington.

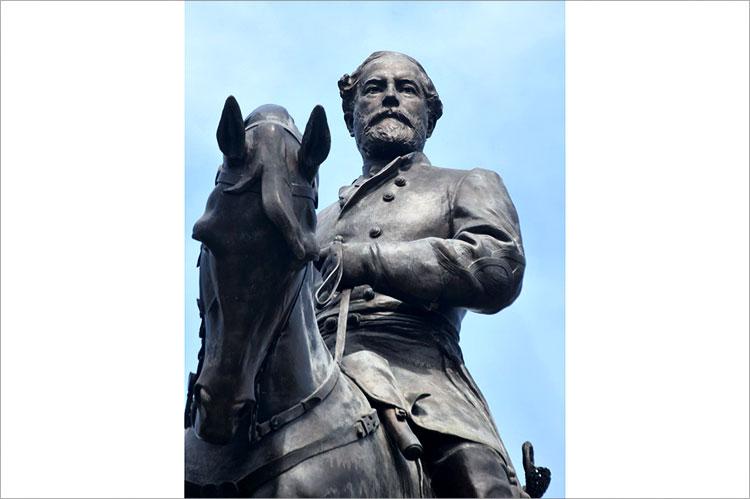

I would like to advance the idea that the Confederates are in a class by themselves. Their statues should be taken down and carted off to museums, and the military bases in question should be renamed. It by no means follows that memorials to the others named above should also be removed. There are two things about the Confederates that don’t apply to the others. There is no slippery slope.

The first and less important thing is that the Confederates were traitors. This is not to say they weren’t honorable men. After all, if the American Revolution had failed, Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, and all the others we consider patriots would have gone down in history as traitors. The historical narrative of the triumphant British Empire would have stressed their disloyalty to established order and the many lives lost in a futile rebellion.

Still, it is unusual — perhaps unique — for a nation to erect monuments to people who tried to take it down. We don’t, after all, have statues of Benedict Arnold or Tokyo Rose in our parks. There must be a reason for this anomaly.

That reason is not difficult to uncover, and it is the second and more important reason to take down these statues and rename the bases. It begins with the fact that the commemoration of Confederate “heroes” was enabled by the collapse of Reconstruction in the decade after the Civil War.

Immediately after the Southern surrender in 1865, the Republicans who controlled Congress generally wanted to exclude the rebel leaders from public life and protect the freed slaves from the retribution that would surely be their lot if the former Confederates regained control. When Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, however, he was succeeded by his vice president, Andrew Johnson. Johnson was a Tennessee politician who had supported the Union in the Civil War, which is why Lincoln picked him. Unfortunately, he proved to be a firm opponent of civil rights for African-Americans.

The Democrats, for their part, were happy to raise fears among working-class white people that the freed slaves would compete for jobs and opportunity.

President Grant, who took office in 1869, did make strong efforts on behalf of civil rights, including suppressing the Ku Klux Klan, but he was hobbled by rising opposition and sidetracked by corruption scandals in his administration. What enthusiasm there was for justice among the people of the North mostly evaporated.

The next president, Rutherford B. Hayes, took office in 1877 after an election in which he lost the popular vote but prevailed in the Electoral College by exactly one vote. The Democrats disputed 20 of those electoral votes. This created a constitutional crisis that was resolved just days before the inauguration. The Democrats agreed to accept the result in return for a promise by Hayes to withdraw the remaining military governors from the South, leaving the way open for whites to regain control throughout the former Confederacy.

What followed was the reign of terror conducted by a resurgent Ku Klux Klan and the imposition of the nefarious Jim Crow laws, which replaced slavery with serfdom.

In the decades that followed, it became politically advantageous to memorialize the Confederate leaders, sending a clear message that Lincoln was dead along with his fine words and that the Confederates had effectively won the Civil War.

These statues should be taken down because their purpose was not to recall history but to celebrate the ascendency of white power in the South. That was the direct result of a decade of betrayal capped by a political deal that enabled slavery in all but name to continue for another century.

John Andrews lives in Sag Harbor.