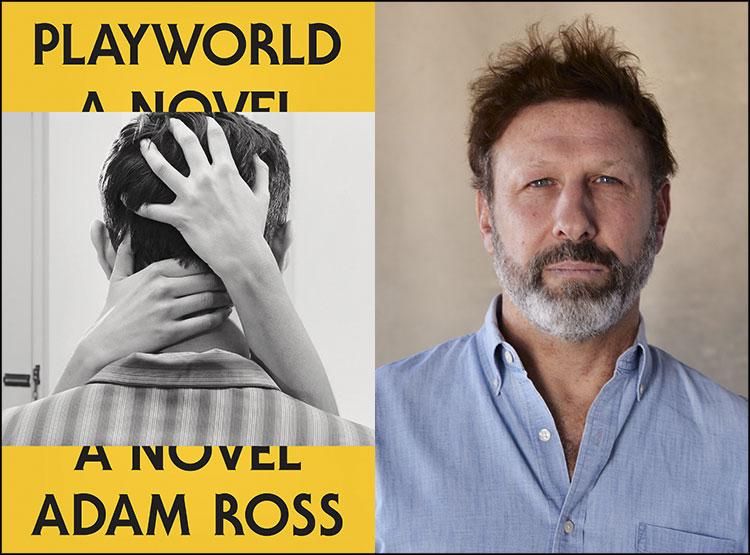

“Playworld”

Adam Ross

Knopf, $29

Griffin Hurt, Adam Ross’s protagonist in his addictive second novel, drops a bomb right off the bat: “In the fall of 1980, when I was fourteen, a friend of my parents named Naomi Shah fell in love with me. She was thirty-six, a mother of two, and married to a wealthy man.” That’s the first sentence of the prologue.

Adam Ross describes “Playworld” as semi-autobiographical, and he’s dedicated it to his father, mother, and brother. The fictional Hurt family of four, a mother, father, and two sons, feels real, as does the New York City he paints with meticulous detail. Griffin’s memories are fully rendered, almost magnified. “Playworld” is shocking at times and completely relatable. It’s also unsettling and funny.

Like every unhappy family, the Hurts hurt each other (and themselves) in their own distinct way. Griffin is a New York City private school kid who works as a professional actor to help pay his tuition. Acting is the one thing that comes easy to Griffin, but he’d give it up to be the star of his school’s wrestling team.

Then there’s Griffin’s smarter, cooler, more popular younger brother, Oren. At 12, he’s mastered the art of self-parenting. “Oren loved the idea of a horse. He had once gotten Dad to take him to Claremont Riding Academy for a set of lessons, which was the only thing I could ever recall the two of them doing alone together.” Like the other Hurts, Oren is living a secretive double life that no one seems to worry about.

On top of Griffin’s job and clandestine sessions in Naomi Shah’s Mercedes (a silver 300SD Turbodiesel), he is grappling with existential loneliness, an abusive wrestling coach, and his loving but emotionally absent parents. There’s also an awkward trip to the Hamptons, a family vacation gone very wrong, a job in a not-Woody Allen movie, and his father’s moving 19-page-long answer to Griffin’s question, “When were you first in love?”

Griffin describes his father, Shel: His “job title — actor — was a broad one, best defined negatively. He was not a television star, although he’d appeared, once, as a surgeon on . . . ‘General Hospital.’ ” Shel Hurt is a pre-boomer with a diva twist. He’s a man in love with the sound of his own voice who mostly ekes out a living as a headshot photographer and vocal coach.

Mr. Ross captures this particular breed of father so perfectly, a reader might be compelled to Google “Is Adam Ross’s father a performer?” (Yes.) Fortunately for the reader his characters are more than their faults. For Griffin, his father’s greatest gift “was not his voice. It was his infuriating charm. It was impossible to stay angry at him.”

Lily Hurt is a beauty, a smarty, and a former ballet dancer with a wall of books in her bedroom. Griffin isn’t the only one experiencing a metamorphosis. Despite Shel’s annoyance, Lily is finishing up her M.A. in literature at N.Y.U., a “pursuit . . . that occasionally drove [Shel] nuts. They often fought about this, sometimes openly, at the dinner table.”

One evening, at a party, Griffin watches the host, Sam Shah, Naomi’s husband, grope his mother while mansplaining Reaganomics at her. Lily catches Griffin’s eye and crosses hers. “At moments such as these, she was the only person in the room I trusted.”

Like Shel, Lily’s parental modus operandi is entirely on her own terms. She may not show up for Griffin’s beloved wrestling matches or dinner, but the instant his summer reading assignment arrives, she takes Griffin to Shakespeare & Company for “Moby-Dick,” “Goodbye, Columbus,” “Middlemarch,” and “Portrait of a Lady.” The latter two “because they’re only the greatest novels of all time.” Lily’s pursuit of autonomy and self-improvement affects her family deeply. No spoiler here, but Lily’s actions in 1980 are bound to impact Griffin and Oren for the rest of their lives.

There’s a moment at some point when children discover that their parents do not belong solely to them. For Griffin, it’s when he stumbles into an intimate moment between Lily and Shel, and although she sees her son, she ignores him: “It was suddenly clear to me that I knew her as my mother but not as a woman, a distinction I’d never previously thought to make; and that in our family’s food chain, Dad was her apex and Oren and I were at the bottom.”

Older Griffin occasionally pipes up, assuring the reader that he did make it to the other side, self-aware and mostly unscathed. “Hindsight reveals several important things about our social lives as city children in a city that, for all intents and purposes, no longer exists. Monied parents like the Adlers left town on the weekends for homes . . . but in their mildly dissociative and benignly neglectful fashion they neither insisted their children join them nor cared much what they did in their absence.”

For all the freedom given Griffin and Oren, Gen X is the last generation of kids who grew up without the shield of screens and video games. For better or worse, back then kids were present with adults, privy to conversation that now is off limits or mere background noise to the more pressing TikTok video d’heure. In those days, even dysfunctional families ate dinner together and actually spoke to one another. They watched the same shows, read the same news, and when a family member left the house, they weren’t reachable nor subjected to location tracking.

Mr. Ross recreates the intensity of the era, dirty and magical, as it was back then through Griffin’s experience: kids at Dorrian’s and Studio 54, subway tokens, and graffiti everywhere. Izod shirts and Uber-free Hamptons. It’s just before AIDS, crack, and yuppies. On top of everything else, “Playworld” is a gift to anyone who remembers that time and place and a history lesson for those who missed out completely.

Adam Ross is the author of “Mr. Peanut.” A native New Yorker who has spent many summers in East Hampton visiting family, he now lives in Nashville.

Heidi Neurauter, a previous book reviewer for The Star, lives on Shelter Island.