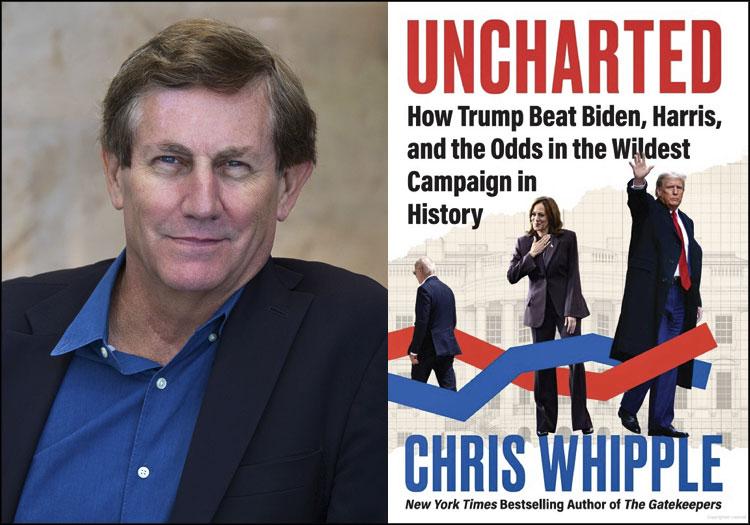

“Uncharted”

Chris Whipple

Harper Influence, $32

In his 2023 book “The Fight of His Life,” the veteran TV documentary-maker turned best-selling political author Chris Whipple focused on the first two years of Joe Biden’s presidency — with a bottom line that remained accurate to the bitter end (and bitter it surely was). Biden didn’t/couldn’t get the credit he deserved for notable successes: fighting Covid, reviving an economy that the pandemic had so crippled, adding more new jobs than any other first-term president. Perhaps more important, the book also contained an early warning of that bitter ending.

In June 2021, Whipple noted, on the Air Force One flight home after eight grueling days in Europe for summits with G7 countries, the European Union, NATO, and Putin, “everybody was absolutely exhausted,” recalled Bruce Reed, the deputy chief of staff. Except for President Biden, who “sat down and told stories most of the way home — easily four maybe five hours of stories . . . a vivid demonstration of unbelievable stamina.”

“Or of a gabby old guy who doesn’t know when to get a needed night’s rest, and focus on the issues ahead,” read a review in The Star (mine). “Voters will decide.”

In fact, actual voters never got the chance, as detailed in Whipple’s latest, “Uncharted: How Trump Beat Biden, Harris, and the Odds in the Wildest Campaign in History.”

Biden’s increasingly shaky mental state at age 81 (a record for Oval Office occupants) led to a disastrous TV debate with Donald Trump and irresistible pressure from Democratic Party leaders (including, sadly, old colleagues and friends like Nancy Pelosi, the still powerful former House speaker) to end his campaign for a second term with barely more than 100 days to the election.

Some saw a White House cover-up of dangerous incapacity at the highest level, others a plague of self-serving self-deception afflicting the president and those who enjoyed their influence in his service.

Of course, Biden initially promised a one-term presidency. But there were some facts in favor of hanging on. He had beaten Trump in 2020 by seven million votes, despite familiar doubts in his own party. And a predicted Republican “red wave” failed to materialize in the 2022 midterm elections, despite high inflation and low Biden approval ratings.

It suggested that a highly emotional issue like abortion could bring significant Democratic strength to the incumbent against what his loyalists feared — and focused on — as Trump’s existential threat to American democracy.

But keeping an ever-weaker Biden under the radar also raised suspicions. Writes Whipple: “One prominent Democrat, an old friend of Biden’s, told me he’d visited the White House twelve times but no one had ever suggested he pop into the Oval Office to say hello. The reason for this seemed obvious to him: The president wasn’t up to it.”

The isolation imposed on Biden was a two-edged sword, protecting his image but also blocking him from the full import campaign experts found in his sinking polls and prospects.

Keeping Biden from confrontations with the press or even concerned supporters, some say, may also have further diminished his ability to defend past and promised policies when onstage with Trump. Most notable was his bizarre, self-congratulatory exclamation that “we finally beat Medicare.” He meant Big Pharma, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre later explained.

As usual, Whipple’s wealth of inside sources, despite all intended secrecy, illuminates the various viewpoints involved: Biden’s, those of top aides and Vice President Kamala Harris, ultimately the presidential nominee and wisely keeping some secrets of her own. She’d been quietly making contingency plans, we learn, with a network of activists untraceable to her assigned to develop strategy and support should Biden withdraw.

Also from insiders, Whipple reports that Team Trump too had its problems, notably the candidate’s willful unpredictability and fury over not getting to run the age-oriented campaign he’d planned against Biden. But the campaign director, Susie Wiles, daughter of the celebrity sportscaster — and alcoholic — Pat Summerall, “knew how to deal with difficult men.” She is now the first woman White House chief of staff.

Wiles led Trump’s campaign’s efforts with single-minded focus on key voter groups including younger minority males who responded surprisingly well to the former president’s dictatorial bluster and bad-mouthing of Harris (“dumber than hell,” “mentally disabled,” “shit vice president,” “Is she Indian or is she Black?”).

His bloody ear and raised fist (“Fight! Fight! Fight!”) after a failed assassination attempt made many see his return as literally heaven-sent. Indeed, “I had God on my side,” Trump boasted toward the end of the G.O.P.’s Milwaukee convention, as he began to surface a new, toned-down, more unity-seeking approach.

But as if bored by his good behavior, Whipple writes, the former president then veered off track. Ignoring a rewritten speech on his teleprompter, he launched a typically partisan attack on Democratic “weaponizing,” the “fake documents case,” “partisan witch hunts,” “crazy Nancy Pelosi,” and “the late, great Hannibal Lecter,” the cannibalistic villain in “The Silence of the Lambs,” now an unlikely G.O.P. crowd pleaser.

Then Biden came down with Covid again. Four years earlier, the disease had provided an effective issue against President Trump and the rationale for Biden’s low-profile campaign from his basement recovery zone. Now it underscored his weakness as more party leaders called for withdrawal.

On Saturday morning, July 20, top aides Mike Donilon and Steve Ricchetti brought their combined 60-plus years of loyal experience with Biden, and much inauspicious polling data, to the president, recovering at his Rehoboth Beach retreat. He was down only a few points nationally, but Trump appeared insurmountable in key battleground states. And even at that his visitors were “soft-pedaling” his situation, Whipple finds, as “within the historical margin” to come back.

“But it will be brutal,” warned Ricchetti, “and you will have to wage a fierce, lonely fight against your own party.” What would quitting sound like? Donilon said he’d write a draft. “I want to sleep on it,” Biden agreed.

Next morning he alerted his chief of staff, Jeff Zients, at the White House. “I’ve decided not to run,” he said, then swiftly turned to his priorities while still in office — legislation to lower costs, protect personal freedoms and civil rights, and address national security issues: Gaza, Ukraine, and China.

That left the issue of who’d replace Biden this late in the race. But he didn’t mention it to Vice President Harris in a first call about his decision, circling back to say his endorsement of her would not come with the formal withdrawal but, oddly, in a separate tweet some minutes later.

Still, the veep’s earlier preparation helped make a remarkably swift start to line up state party leaders and convention delegates, super delegates, labor unions, and reproductive rights groups.

Biden had decided there was not enough time for a formal primary that many party leaders favored but which might alienate Black Democratic voters and divide others. Whipple also reports it was financially and legally “unworkable.” Only Harris, already on the ticket, might be entitled to campaign funds so far contributed, some argued.

Though Biden was feeling abandoned, especially by former President Barack Obama, Whipple reports that he and Zients gave Harris explicit permission to break with him on policy to win a “change election.” (This contradicts another recent campaign account, “Fight” by Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes, which says Biden repeatedly advised Harris to “let there be no daylight between us.”)

In the wake of Trump’s win, by a relatively narrow 1.5 percent in the popular vote, Whipple sought analysis from Leon Panetta, 86 at the time, former congressman, White House chief of staff, Office of Management and Budget director, C.I.A. director, and secretary of defense. He blamed Biden, his friend of 50 years, for not seeing his inability to block Trump “at an early stage where it could have made a difference in the competition . . . to get the nomination.”

He blamed Harris for not sufficiently separating herself from the president, whatever the intraparty pressures.

“They were just too hesitant,” Panetta says, “thinking they could tiptoe into the presidency without getting anybody pissed off at them. Baloney. You’ve got to make the American people understand that you’re tough enough to be president.”

Panetta also recommended that Democrats take a clear-eyed look at Trump’s powerful, angry appeal, “the chemistry that produced this era for reasons that are very real out there in the country.”

Whipple ends with a challenge to Susie Wiles. “The woman who helped Trump beat Biden, Harris, and the odds . . . carries a profound responsibility,” he writes. “She represents the thin line between the president and disaster.”

But the shock of mass arrests by masked ICEmen around the nation, military occupation of Washington, and chaos in key government offices, from education to foreign aid, may well indicate that the line has already been crossed — if not erased — at least for the time being.

Chris Whipple summers on Shelter Island.

David M. Alpern of Sag Harbor was a reporter, writer, and senior editor at Newsweek magazine, anchor of “Newsweek on Air” and the independent “For Your Ears Only” radio broadcasts for more than 30 years, and now hosts programs for local libraries.