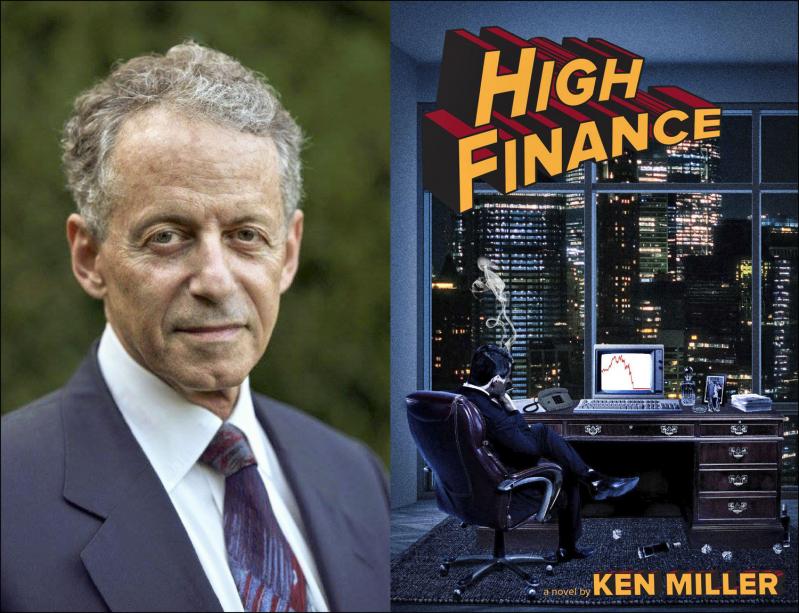

“High Finance”

Ken Miller

Ulysses Press, $27.95

“High Finance” is a satire and, as a satire should be, at once amusing and serious. It traces the personal evolution — from adolescence to . . . too old for the game — of one Jed Czincosca (the initial C is presumably silent). Whatever, Jediah is the child of a down-and-out Jewish family from Chicago.

Jed and his older brother are sons of a no-good failure of a father and an entrepreneurial mother whose secret partner in business is a Chinese restaurateur. Dad’s employment history, following his return from World War II, started as a salesman for the Maidenform company, “which had segued from supporting the troops through its parachute harness business to supporting women’s breasts.”

He soon quit to develop his own private schemes such as hiring boat captains to execute his sales for “at sea” burials. The elder son, Lenny, is a liberal purist who becomes an academic, but our hero, whose early preparation for Wall Street was at the knee of his father and his harebrained schemes, has a taste for the con from Day 1; “as the two of them knew, Jed was virtually a clone of their father.” Jed will inherit his father’s chutzpah but is hell-bent not to fail.

The text is full of aphorisms derived from Wall Street culture, starting with the advice given to Jed during his interviews for a place at Lehman Brothers: “Don’t trust your clients or your partners,” or “Some of my partners have criteria for talent which would not be tolerated in a true meritocracy.” You get the tone. The overarching theme of this rake’s progress will be greed.

Woven into the narrative are the lives of various participants in Jed’s life, among them his cunning British secretary, Deborah Cunningham, who after a honeymoon start to her job felt that “for every positive descriptor of Czincosca, she could suddenly, it seemed, think of a negative: self-assured/egotistic; well-groomed/vain, obsessive about his personal appearance; intense/moody; focused/largely ignorant of anything but business; nice to subordinates . . . calculating; ambitious/ruthless.”

There is of course the wife, Amanda, banished from home by a rich WASP father for what he deemed her permissiveness and then charmed by Jed’s self-assurance. “I need to be very wealthy,” he told her, “extremely rich.” She went for it. Along the way, we meet a Russian nanny to the Czincosca children who describes her former employers as “oilygarchs.”

The stage for this tongue-in-cheek drama is the Wall Street firm Lehman Brothers. When Jed joins, they are flying high and Jed is so sure of their ever-rising success that he invests all his gains in Lehman stock. “I must admit,” he tells us, “that from the first day I walked in through the Lehman doors in ’77, I had been obsessed with owning as many shares as I could get my hands on. When I saw the returns on capital Lehman was getting it was clear there was no more reliable way to wealth than owning as much of the Firm as possible.”

He even borrows $100 million to buy some more when the price of Lehman stock falls — he thinks — temporarily. In order to borrow such a huge sum he has to give his personal guarantee based on the value of shares he already owns. Oh, dear.

“On this cursed day, September 15, 2008, I have lost the power of speech. Horrible as it is that Lehman Brothers, the Firm I dedicated thirty-one years of my professional life to, has declared bankruptcy, it’s even more horrific that I . . . will need all the luck and skill I can muster to avoid the same personal fate.”

He later continues: “When I came to The Street in the seventies, we were the best and the brightest, allocating oxygen to the creatures of the economy; we decided which enterprises got to breathe. Suddenly we were only ‘banksters,’ leeches on society. Not only was I wiped out, but I was forced to live with the new reality that bankers were to be blamed for everything.”

So, how does our author conclude the lesson Jed learned in high finance?

I will leave that for the eager reader to discover. Jed concludes, “We all have opinions on who has better information. That’s what makes markets.”

Ana Daniel, retired from business and academia, lives in Bridgehampton.

Ken Miller, a financier, also lives in Bridgehampton. His writing has appeared in magazines including The New Republic, Fortune, and Foreign Affairs. “High Finance” comes out Sept. 2.