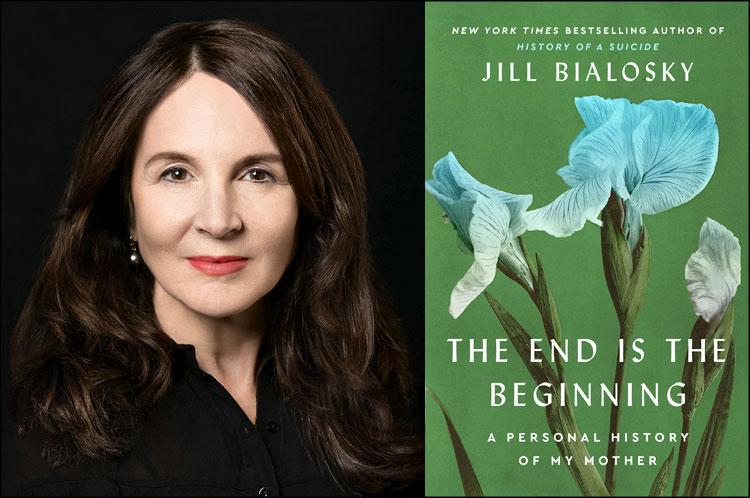

“The End Is the Beginning”

Jill Bialosky

Washington Square Press, $28.99

William Meredith, in his poem “Parents,” writes, “Everything they do is wrong, and the worst thing, they all do it, is to die.” Jill Bialosky’s mother, Iris, compounds that worst parental offense by dying during the Covid-19 lockdown of 2020, in a nursing home in a distant state.

So there are no deathbed farewells for her second-eldest daughter, who can’t physically attend her mother’s funeral or take part in the Jewish rituals of mourning, except for reciting a blessing and lighting a memorial candle. Feeling “estranged” from her mother’s dying, she watches the “jerky kaleidoscope” of the rain-blurred graveside service on a 4.7-inch telephone screen, on FaceTime — that phenomenon of modern communication. “Straight out of a dystopian novel,” Ms. Bialosky says about life and death in the time of Covid.

The masked rabbi has met Iris, but must still garner details about her from her three surviving daughters for his brief eulogy. They tell him that she was a loving mother who’d raised them on her own after her husband’s death when she was only 25, and that she was in her 50s when she lost her youngest daughter.

“The End Is the Beginning” is an eloquent and moving account of Iris Yvonne Bialosky’s life, recalled backward, as the title, gleaned from T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” suggests. The book serves as a more complex eulogy for the writer’s mother — “She was beautiful. She liked to laugh. She liked men.” — and a nuanced examination of aging and of the mother-daughter bond. “One night I look at stars in the sky from my deck. There’s Andromeda with her daughter, it looks like it’s one star, but it is really two. Death cannot tear my mother apart from her daughter.”

Iris Bialosky died at the age of 86, after enduring years of depression that eventually devolved into the dementia of Alzheimer’s disease. As memory, personality, and autonomy are relentlessly stripped away, Iris’s daughters are far more than simply dutiful in caring for their failing mother. They’re dedicated to mitigating her psychic pain — visiting often, bringing treats, polishing her nails, and thrilled that she recognizes them — while easing her into the major life changes that must take place. The house in which Iris has lived for 50 years will be sold, and eventually supplanted by institutional care in the Fairmount (memory care) Unit of Menorah Park, in the company of strangers.

As her daughter Jill writes, “We rarely think of freedom until it is taken away from us.” She cites “The small undertaking of being able to go into the privacy of a bathroom, sit on the toilet for as long as is needed or desired,” a place where one might also read or cry in solitude.

While Jill and her sisters, Cindy and Laura, begin to downsize their mother’s worldly goods, “Jilly” (as Iris affectionately calls her) is expanding her own. Workers are replacing the deck of the Long Island house she currently shares with her husband and son with a much larger, more elegant one, even as her childhood home in Ohio goes up for sale. The new deck construction — “like a grand theater” — had begun before her mother’s life went into crisis mode. She thinks that if her mother were there, she’d be ordering the workers around “like she used to do when she remodeled our house.” The daughter seems to be restoring, in her own mind, at least, the mother’s lost energy and agency.

It’s not surprising that Ms. Bialosky — a poet, novelist, essayist, and editor — finds examples of illness and death in literature. Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain,” Dante’s “Inferno,” Atul Gawande’s “Being Mortal,” and “Blue Dementia,” a poem by Yusef Komunyakaa, among numerous other works, provide parallels to Iris’s circumstances for her literary daughter. Mann’s novel lends itself most pointedly and poignantly to analogy. “Like the characters in the Berghof sanitarium of ‘The Magic Mountain,’ the residents in the Fairmount Unit live a hermetically sealed and ordered life. There is no stopping the progression of the body’s demise.”

Iris Bialosky endured several personal tragedies, beginning with the death of her own mother when Iris was 9 years old, and culminating with the suicide of her 21-year-old daughter, Kim, the only child of her failed second marriage. Jill Bialosky wrote about Kim in a previous memoir, “History of a Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life.” In this one, she depicts her mother’s grief over that loss as indelibly as she portrays her descent into forgetting.

I had some trepidation at first about reading and reviewing “The End Is the Beginning.” Both my mother and father suffered from dementia during their final years — an inferno, indeed. Why would I want to be reminded of that miserable time? But I was reminded, as well, by this fully rendered and loving portrait, of my parents’ previous sentient, delightful selves — of happier times.

And I recalled poems that I chose to reread soon after their deaths and since, like William Meredith’s “Parents.” Leaving my parents’ apartment for the last time made me think of Philip Larkin’s poem “Home Is So Sad,” with its inventory of ordinary household objects “bereft of anyone to please.” And I often think of the poet Linda Pastan writing of her parents in her 70s, “I thought I’d always be their child.” Jill Bialosky was Pastan’s editor, and one can imagine the flow of sympathetic understanding between them.

What those memorable poems and a well-written, deeply personal book like this one offer are a shock of recognition and a sense of community: Someone else has experienced this; someone else has felt the way I feel. Validation and consolation — perfectly good reasons to read.

Hilma Wolitzer’s most recent book is “Today a Woman Went Mad in the Supermarket.” She and her husband formerly had a house in Springs.

Jill Bialosky, executive editor at W.W. Norton, lives part time in Bridgehampton.