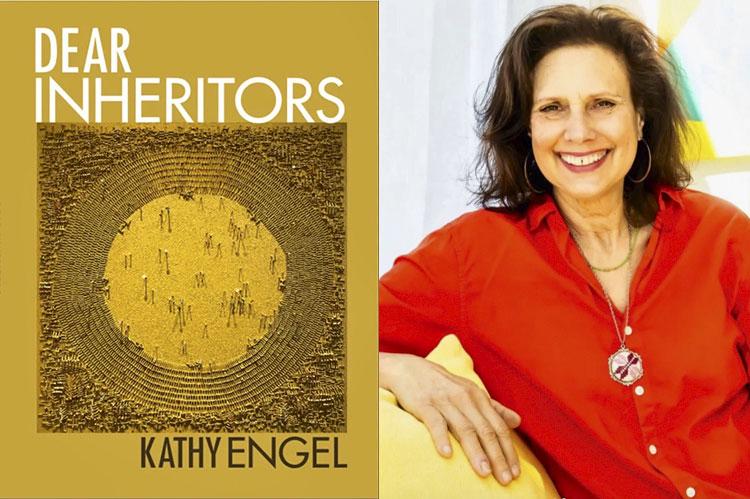

“Dear Inheritors”

Kathy Engel

Get Fresh Books, $18

The title of Kathy Engel’s new collection, “Dear Inheritors,” is a greeting, what in the parlance of letter writing we call the salutation. To greet, to open a channel for connection, to signal friendliness over suspicion: This sociable act, this most human/humane of verbs, is characteristic of Ms. Engel’s lively, timely collection.

Her poems don’t sit still, even when meditating on serious subjects. Someone knocks, they jump up to answer the door. Many, as the title suggests, take the form of direct address, to the reader or a friend or the poet’s beloved or the poet Mosab Abu Toha, enduring Gaza’s horrors. All of these poems are superb hosts, which is not to say they don’t pack some tough truth. They do. They just don’t deliver it in a monologue. Truth, as Ms. Engel sees it, is a conversation.

Take the first line of “August letter to a poet,” for example: “This gorgeous country loves to make a summer,” it reads, and deftly invites us in. But by the second line, we’re deep in conversation, and by line five, we’re asking big questions about the violence that this country also seems to love. Here’s the whole passage:

This gorgeous country loves to make a summer

orphan or take a parent’s child. The tree will soon

articulate its loss, first flush, then naked limbs.

Geese announce their discipline. What can I

discover from their V-shaped flight?

One such discovery later in the poem comes in the rhetoric of invitation: “Let’s train each muscle’s syllabus / of love no matter the attempts to rip it raw.” Love answers violence, love is urgent, but it’s urgent without the urging. A lesser poet would have written “Train each muscle’s syllabus” instead of “Let’s train each muscle’s syllabus.” Throughout this collection, Ms. Engel explores the conversation between love and violence alongside the language we use to express both. We can do violence with words; we can also enact love with them, by using “Let’s” instead of the command form of “train,” a grammar shaped by love. And “love is an action,” the poem “What’s Another Word for Genocide?” reminds us.

Symbols other than words contain similarly contrasting potentials, and Ms. Engel explores those as well. “Now listen,” a poem written “On the occasion of the rescinding of Angela Davis’s Fred Shuttlesworth Award by the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute,” as the epigraph tells us, ends with this powerful image:

Dear Birmingham

you can’t rescind

a daughter:

Angela

messenger

of the gods

you can’t un

light

a torch

The line break at “un” breaks more than a line, it breaks a whole history of oppression, converting a No into a Yes, converting symbolic violence into love, and leaving us with the thing we can do: light a torch. This line break, one that would do Eileen Myles proud, is not the only flash of technical mastery. Lots of poems take on forms, playfully and expertly. One is modeled on Gwendolyn Brooks’s “When you have forgotten Sundays,” another writes itself forward, and then backward. Tankas abound.

“Dear Inheritors” is brimming with poems either written during or recalling the Covid pandemic. Remembering how starved we all were for physical touch, even as we were horrified by it, remembering how connection then was both salvation and death, this collection begins the necessary work of processing that trauma, always in the context of the many other traumas (war, the mass graves of Indigenous children, victims of police brutality) that humans inflict on one another.

Ms. Engel has lit a torch. Let’s look up to see the “democracy of birds in flight,” for there are “no borders in the air,” let’s listen, let’s read our way forward, let’s follow the light.

Julie Sheehan is an associate professor in the creative writing program at Stony Brook’s Lichtenstein Center and the author of poetry collections including “Bar Book.” She lives in East Quogue.

Kathy Engel of Sagaponack is an associate arts professor at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.