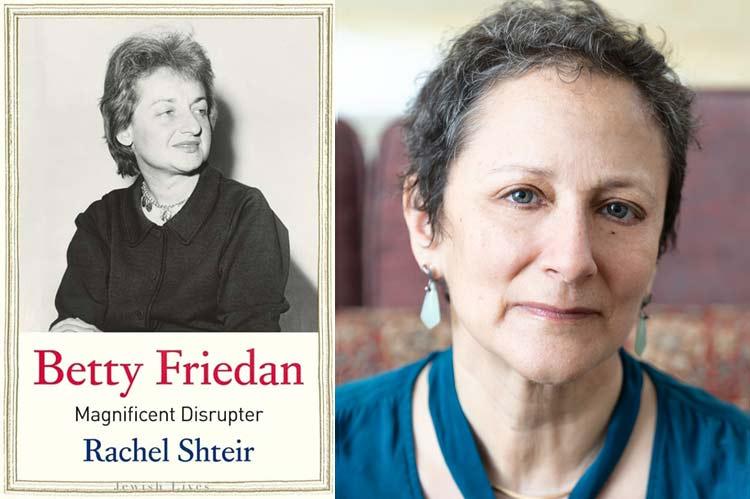

“Betty Friedan: Magnificent Disrupter”

Rachel Shteir

Yale University Press, $27

Last week my grandson announced he is becoming a feminist.

"How come?"

Reading for a college paper, he recognized that the legal and social inequities affecting the lives of women are not fair. Happy to have another subject to share with him, I mentioned Rachel Shteir's new biography.

"Who's Betty Friedan?"

In her intro, Shteir writes: "Since Friedan's death, the practice of either ridiculing her or making her disappear continues, carrying forward the portrait cemented twenty years ago in the last round of full-length biographies."

The practice of Betty's erasure explains why a person born in the 21st century may have little or no knowledge about one of the giant visionaries of the 20th century, a visionary who made us aware of many of the challenges our society continues to experience.

My own life was significantly changed by Friedan's work, and I had the privilege of meeting her, but it wasn't until I read Rachel Shteir's book — a work of excellent scholarship, documented by 56 pages of notes — that I learned the full scope of Betty Friedan's life. Shteir tells all — her triumphs, her failures; her strengths and weaknesses. The good. The bad. The ugly.

Despite Friedan's initiating the second wave of feminism in the U.S. in 1963, when her revolutionary book, "The Feminine Mystique," exploded conventional norms, her volatile temper, aggressive comments, and competitive nature contributed to her being pushed aside by many notable feminists during her lifetime. Topping the list are Gloria Steinem, Kate Millett, Bella Abzug, and Germaine Greer.

The 2020 TV series "Mrs. America," a docudrama about Phyllis Schlafly's war against the Equal Rights Amendment, also contributed to a very unlikable version of Friedan, without balancing the presentation with her vast contributions to society.

Shteir points out that some of Friedan's decisions alienated younger women and drove them to initiate the third wave of feminism. Friedan's huge blunder was excluding gays and lesbians from the movement. She is vilified to this day for calling lesbians "the lavender menace."

Friedan had a rationale for this obvious discrimination. She believed such women would give substance to the idea that feminists were, at the very least, man-rejectors, if not man-haters. This, she believed, would keep the population at large from accepting her agenda, which was to promote sexual and reproductive freedom, higher education and equal pay for women, and to pass the E.R.A. She believed it best to keep sexual identity out of the equation.

Her caustic personality was a notable obstacle to her continued leadership. Another was the difficulty of marginalized women identifying with the struggles of privileged women. Black, brown, Indigenous, lesbian, poor, and homeless women, as well as single mothers, couldn't empathize with such a luxurious problem as feeling unfulfilled. In time, members of these groups who began their own journeys toward equality and power rejected Friedan's perspectives. They felt unseen.

Shteir's biography attempts to reclaim Betty Friedan from relative obscurity and trace her pursuits to her culture of origin. Published by Yale University Press in its Jewish Lives series, the book is part of a sizable collection that includes people from antiquity to present times. Think "Moses" to "Barbra Streisand," "Ruth" (wandering among the alien corn) to "Mel Brooks." (Seriously? Yes!)

In the granddaddy of ironies, the publisher of the series is the same Yale whose admissions chairman, in a 1922 memo, urged limits on "the alien and unwashed element" (translation: Jews). That memo led to the imposition of the 10-percent quota on Jewish enrollment at Yale that lasted until 1960.

Shteir makes the case that Judaism, with its focus on justice, was responsible for the progressive causes Friedan promoted. Her maternal grandfather, who settled in Peoria, Ill., was an immigrant who became a medical doctor. He descended from a long line of rabbis and kept the faith. In Peoria, where she was born and raised, Betty experienced or witnessed injustice at home, in the schools, and in other establishments.

She experienced antisemitism as a child, and her traditional Jewish family set limitations on her ambitions. Her mother didn't want her to go to Smith College, even though she had an I.Q. of 180 and excelled in her studies. Her mother wanted Betty to be in an environment where she could find a suitable husband and acquire the highly coveted M.R.S. degree.

These constrictions led Betty to see women's rights as civil rights. Like civil rights leaders whose goal was for people of color to be recognized and treated as human beings, Betty's goal was to have women recognized "as people, too" — people whose lives should include the rights enjoyed by men.

I suspect I am among many who thought of Betty as a suburban housewife who recognized her dissatisfaction with a life limited to home and family. I was unaware of the volume and breadth of writing she had done prior to "The Feminine Mystique." I had no idea how her articles for union newspapers and other political publications went hand in hand with her activism on behalf of progressive causes.

Marriage and the birth of her three children did not stop her work, study, and activism. What did change was her emergence as a public figure and, eventually, a celebrity known around the world. Her prominence, along with her legendary energy, led to her writing, speaking, marching, organizing, and traveling all over the globe to promote women's rights. She co-founded the National Organization for Women, the National Women's Political Caucus, and the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, or NARAL.

Betty understood that her vision for radical change in the lives of women after thousands of years of patriarchy would be an uphill battle. The hill was no less significant than Mount Sinai. After all, Betty was quite aware of a daily prayer recited every morning by observant Jewish men: "Blessed are you, Lord our God, Ruler of the Universe, who has not made me a woman."

Though the other Abrahamic religions that came after Judaism may not include that particular prayer, its sentiment is behind the unequal status of women which they have supported.

Later in life, Freidan studied Judaism, spent time in Israel, and attended synagogue. At her funeral in 2006, Joy Levitt, a female rabbi, officiated. In Sag Harbor's Jewish Cemetery, another female rabbi, Jan Uhrbach, spoke at the graveside service: "Look, if it wasn't for her, I wouldn't be here."

This is what countless women all over the world can say, thanks to Betty Friedan's vision and activism. And because of Rachel Steir's book, the news will be passed to new generations who will carry on Friedan's work.

Fran Castan, the Walt Whitman Association's Long Island Poet of the Year in 2013, is the author of "The Widow's Quilt," a book of poems, and "Venice: City That Paints Itself," a collection of her poems and paintings by her late husband, Lewis Zacks. Formerly of Springs, she lives in Greenport.

Betty Friedan lived in Sag Harbor. "Betty Friedan: Magnificent Disrupter" is a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award in biography. The awards ceremony is March 21 at the New School in Manhattan.