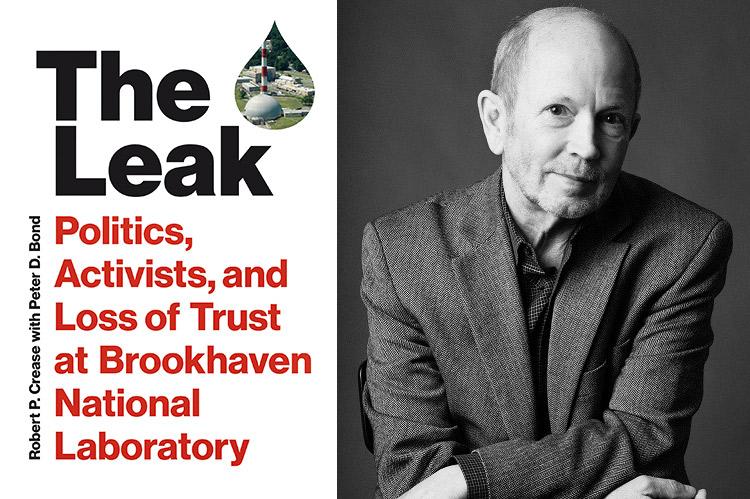

“The Leak”

Robert P. Crease with Peter D. Bond

MIT Press, $29.95

In 1997 a leak of water containing radioactivity was found at Brookhaven National Laboratory, which was established in 1947 at a former Army base in central Long Island. The radioactive element was tritium, an unstable form of hydrogen. It emits beta radiation that is too weak to penetrate skin, but which, in the words of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, "can cause cancer if consumed in extremely large quantities."

The publicity surrounding this occurrence created a firestorm of controversy. "The Leak: Politics, Activists, and Loss of Trust at Brookhaven National Laboratory" was written as a 25-year look back by two people who were close to the action.

One of the book's authors, Robert P. Crease, is the chairman of the philosophy department at Stony Brook University. At the time of the incident, he was completing a book on the first 50 years of Brookhaven Lab's history. During the controversy, Stony Brook became part of a consortium that now manages the laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy. The other author, Peter D. Bond, is a retired physicist who worked at the lab for 43 years and served as interim laboratory director during some of the period covered by the book.

As one would expect, they strongly criticize the laboratory's main antagonists, but they also acknowledge errors made by the management. Disclosure: I worked at Brookhaven Lab at the time of the incident. My research was on energy-efficient buildings in a department organizationally distinct from anything nuclear.

The authors had two objectives in writing the book. The first was to show that the leak, which came from the spent-fuel pool at Brookhaven's High Flux Beam Reactor, was extremely small and never a threat to anyone. They point out that the total amount of tritium in all the groundwater was less than that in a single exit sign of the type that uses tritium to keep it lit when there's a power outage. They also point out that the groundwater plume containing tritium never progressed beyond the laboratory's boundary.

Second, they wished to recount in detail how a political struggle involving science can unfold in an atmosphere of fear and mistrust, from which useful lessons can be learned. Because of my past association with the laboratory, anything I might say on the first point is likely to be discounted, so I will concentrate on the second.

The book describes several strategic and tactical advantages that the anti-Brookhaven activists possessed. One of these was the practical lessons they had learned in the fight over the Shoreham Nuclear Plant in the 1980s. They emerged from that fight energized, experienced, and savvy. In contrast, the laboratory was managed by scientists with little previous exposure to the bare-knuckled world of public dispute.

A second advantage for the activists was public suspicion generated by recent cases in which major polluters had covered up their misdeeds. A third was reports that the incidence of breast cancer on Long Island was above the national average. People could easily believe that the laboratory was responsible.

The authors relate how the laboratory's relationships with members of Congress representing our area became difficult as the politicians saw which way the wind was blowing. Administrators at the Energy Department also became concerned, not just with the substance of the issue, but with the atmospherics. They realized that other national laboratories and nuclear weapons facilities had environmental problems far worse than Brookhaven's. They were concerned that the whole national laboratory system might be jeopardized if the controversy spread across the country.

Also to the activists' advantage was their ability to say whatever they wanted, true or not, without being challenged by the local media. "The Leak" cites numerous examples of false or misleading information put out by the laboratory's opponents. The laboratory, in contrast, was bound by strict reporting requirements that made even small incidents seem like major polluting events.

The book also explores how Brookhaven's opponents had an easy time casting doubt on any scientific findings that tended to vindicate the laboratory. I'm reminded of Salem, Massachusetts, in the 1690s, when nearly everyone believed that witches were an existential threat to the community. To deny the existence of witches only brought on the accusation that one was oneself a witch.

Similarly, in the 1990s many Long Islanders believed that Brookhaven was a major polluter. It was, after all, a Superfund site. Consequently, anyone who presented evidence that favored the laboratory was presumed to be in on "the cover-up." When an extensive study showed no prevalence of cancer in the area, it was denounced as bogus merely because Stony Brook University scientists were involved.

The unevenness of the fight was frustrating to many researchers at the laboratory, but it was simply the cost of living in a democracy. In 1940 Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, writing the unanimous opinion in Cantwell v. Connecticut, said, "In the realm of religious faith, and in that of political belief, sharp differences arise. In both fields, the tenets of one may seem rankest error to his neighbor. To persuade others to his point of view, the pleader, as we know, at times resorts to exaggeration, to vilification of men who have been, or are, prominent in church or state, or even to false statement. But the people of the nation have ordained, in the light of history, that, in spite of the probability of excesses and abuses, these liberties are, in the long view, essential to enlightened opinion and right conduct on the part of citizens of a democracy."

The protection of freedom of speech, which despite the words in the Bill of Rights took two centuries to develop in America, is too precious for anyone to advocate restriction for any cause other than outright sedition, reckless endangerment, or slander against private individuals. I would much rather live in a country like ours, in which activists can say almost anything without fear of retribution, than in one like Russia, where even those who speak only the truth are sent to the gulag.

That said, we citizens, as well as those in the media who are often our only eyes and ears, need to question the accuracy not only of those who speak for the government but also of activists, celebrities, and others who are under no legal compulsion to adhere to what is true. In a society in which a free press is the ultimate defense against tyranny, individual reporters have an obligation, as sacred as it is unenforceable, to seek the whole truth of public matters regardless of acclaim or opprobrium.

The book is well documented, with more than 500 references. If you have an open mind and an interest in science and public affairs, I'd say read it and draw your own conclusions.

John Andrews has a Ph.D. in physics. He lives in Sag Harbor.

Coverage by The East Hampton Star and letters in its pages from Alec Baldwin and the late Leon Jaroff, the founder of Discover magazine, are featured in "The Leak," as are numerous articles by Karl Grossman, the veteran local journalist.