“The Ferguson Brothers Lynchings on Long Island”

Christopher Verga

History Press, $23.99

Staggering news of a fatal police attack on an unarmed Black man in Memphis, George Floyd's murder in 2020, and Rodney King's beating by Los Angeles officers in 1991 are each points on a vast continuum of violence that reaches back over hundreds of years and across the Atlantic, to the West African slave trade.

The killing of two Black brothers and the wounding of another in Freeport by a white police officer who never faced charges, on Feb. 5, 1946, was another moment of shame in this tragic history. Yet, though it briefly focused national attention on Long Island, these deaths and what followed were rarely mentioned in the ensuing years.

Also only dimly remembered is the context in which Joseph Romeika, a Freeport police officer, pulled his .38 revolver that night and pulled the trigger once, instantly killing Charles Ferguson with a shot to the chest, then firing a second time, the bullet passing through his brother Joseph's shoulder and lodging in the brain of a third brother, Alphonso, who was dead within hours.

In his new book, "The Ferguson Brothers Lynchings on Long Island: A Civil Rights Catalyst," Christopher Verga describes the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the period between the world wars, as in a Feb. 12, 1923, incident when members of the Klan burned a cross close to a celebration held at the Municipal Auditorium in Freeport by Black Long Island residents to mark Abraham Lincoln's birthday. The Klan simultaneously torched two other crosses in Nassau County that night: one in Lynbrook and another in Long Beach.

Charles Ferguson enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps in 1941. In his enlistment photograph he appeared older than his 22 years, with a pencil mustache, deeply cleft chin, slicked-back hair, and an arched right eyebrow. Charles's brother Edward enlisted in the Army in May of that year and was sent to Camp Upton in Yaphank. Richard Ferguson joined the Army in 1943 and fought with the Third Army in Germany under the command of Gen. George Patton. Joseph Ferguson enlisted in the Navy in 1943 as well, when he was just 16. Alphonso never served in the military; frail and 116 pounds, he was too small, Mr. Verga writes.

Courtesy of Wilfred Ferguson

On the night of Feb. 4, 1946, Charles put on his military uniform with the plan to celebrate his enlistment into a segregated paratrooper unit and met his brothers at their childhood home in Roosevelt. Richard, too, put on his uniform. After staying at the house for a short time, the brothers left for Eddie's, a Hempstead beer garden. As the night got later, they boarded a bus to Freeport to get something to eat at the Texas Ranger restaurant. After downing their hamburgers and coleslaw, the brothers paid up and left for the short walk to the Tea Room, a coffee shop at the Freeport Bus Terminal. It was there that the night took a turn.

An eyewitness described what happened next. Entering the shop, the brothers asked for coffee, but the manager refused to serve them. Charles was quickly angry and, according to the testimony in subsequent investigations, had to be held back by his brothers lest he go behind the counter to rough up the manager. Taken outside, the manager would tell police, Charles kicked or punched a window at the Sinclair and Raynor Oil office on Henry Street, breaking the glass.

Officer Romeika was on patrol that night near the bus terminal when the manager called to him, saying that Charles had said he had a gun and had threatened him before breaking the window. Romeika noticed the Ferguson brothers on foot and stopped them. What actually took place next varied among the witnesses and surviving brothers. Most accounts agree that Charles called Romeika a son of a bitch and Romeika answered more or less in kind. Romeika then kicked Charles in the groin and Joseph on the hip and pulled his gun. By then, a fifth Black man, a worker from a nearby restaurant, appeared, and Romeika ordered him and the brothers up against the oil company wall.

As Romeika went to a call box to get additional police, Charles yelled, "You get home on leave, and the cops want to lock you up." Within seconds, Romeika fired two shots from his service revolver, killing Charles instantly with one bullet, the other passing through Joseph's shoulder and into Alphonso's skull. Doctors declared Alphonso dead about seven hours later at Meadowbrook Hospital. No gun was found at the scene, other than Romeika's.

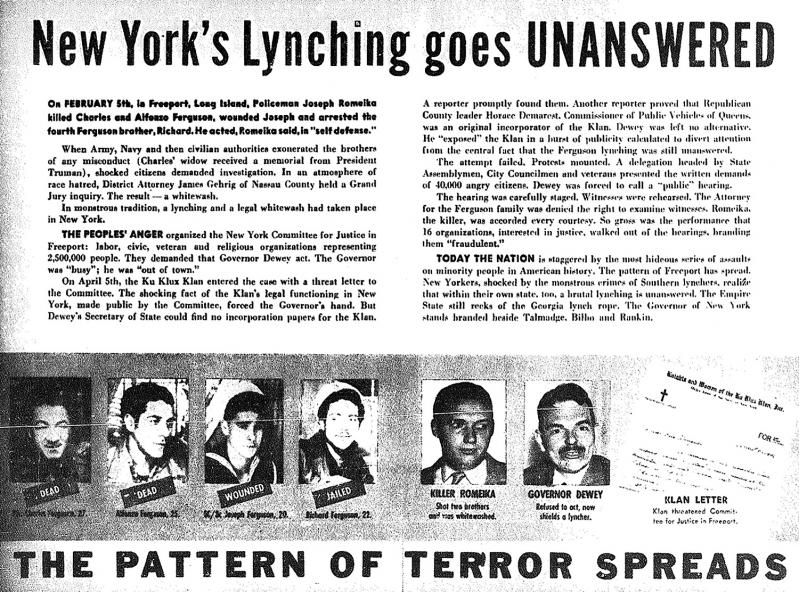

News that two unarmed Black servicemen had been shot and killed by a policeman trickled out of the community, slowly at first, then gathering momentum. The only unharmed brother, Richard, was found guilty of disorderly conduct in a summary trial, fined $100, and sentenced to 100 days in jail. The village justice in the trial had been a member of a pro-Ku Klux Klan political party and a captain in a Freeport Fire Department company that had sponsored the annual Klan Cup Fireman races.

On Feb. 7, a delegation of several local religious leaders, political activists, and veterans went to the Freeport police headquarters to confront the chief. Romeika had not been suspended nor was there any investigation by his superior officers.

Courtesy of the University of Rochester’s Thomas Dewey Archives

Pressure grew on the county district attorney to look into the matter. Mr. Verga provides the details of the grand jury probe, which in short order moved from the incident itself to allegations that the outcry was being orchestrated behind the scenes by communist sympathizers. Few were surprised when the grand jury declined to indict Officer Romeika on any charges.

The acquittal only intensified the sense of outrage among the Ferguson family's growing number of supporters. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell was the keynote speaker at a Make Freeport Free rally held in New York City shortly after the verdict. Newsday and The New York Times intensified their coverage of the case, while civil rights organizations pumped out pamphlets and broadsides, such as a 16-page booklet on the murders, "Dixie Comes to New York." The NAACP's special counsel, Thurgood Marshall, repeatedly wrote the office of Gov. Thomas Dewey, demanding a state investigation. The folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote a song about the shooting. Some 1,500 union garment workers paraded in Manhattan to demand justice.

The whirlwind continued, with counterdemands that the matter be dropped coming from such groups as the Long Island Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. In April, the Klan announced the reorganizing of a dormant chapter in Freeport, which would be watching and noting who was in attendance at any further rallies for the Ferguson brothers.

In July, Governor Dewey relented and appointed a lead investigator, but the outcome was foreordained. Meanwhile, the Federal Bureau of Investigation became interested and opened a secret investigation of its own. Neither would satisfy those sympathetic to the Fergusons.

Mr. Verga observes that the murders' most significant impact was that they set in motion a groundswell call for national change. They were part of a foundation that helped build the postwar civil rights movement.

Christopher Verga teaches history at Suffolk Community College.