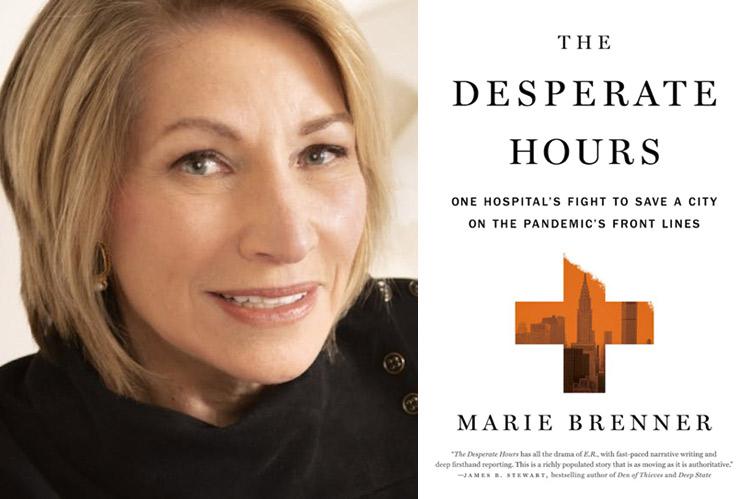

“The Desperate Hours”

Marie Brenner

Flatiron Books, $29.99

The prizewinning journalist and author Marie Brenner has written of war zones before, but never one this close to home and with so many civilian victims: 41,677 dead across New York City, more than a million nationwide, and nearly 10 times that number impacted to greater and lesser degrees.

"The Desperate Hours" is Ms. Brenner's grueling account of how the vast New York-Presbyterian health care system — 11 hospital campuses with 47,000 employees — battled, survived, succeeded, and now fights on against the killer Covid virus. In it she finds a metaphor for the special spirit of the city that she loves.

"Of course, a version of this happened at almost every hospital in America," she writes. "But in New York, at the city's most elite hospital system, it happened before it happened anywhere else and with both greater velocity and catastrophe."

In fact, we learn, Ms. Brenner's story really starts here on the East End, at the Sag Harbor home of Dr. Stephen Corwin, a cardiologist who rose from resident to president and C.E.O. of New York-Presbyterian, as he and Ms. Brenner set ground rules for how she could tell the warts-and-all account he wanted of his hospital's triumphs and tragedies from the earliest days of the pandemic from China that is still with us.

As science clashed with politics, ideology, ego, bureaucracy — and the virus — we see both super-doctoring and spin-doctoring by political figures like President Donald Trump, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Mayor Bill de Blasio, as well as by hospital leaders below Dr. Corwin who were determined to save lives but also save the premier image of New York-Presbyterian that they so cherished — and depended on for essential public and private support.

Front-line workers could not escape the daily terror of contamination for themselves and their loved ones. But remarkably most felt obliged to spend endless hours with a tsunami of the already infected — feverish, gasping for breath, hallucinating, comatose, dying — through the long months before there were sufficient tests or any established treatment beyond intubation with powerful ventilators that in too many cases could do more harm than good for lungs already being destroyed by Covid.

And with ever-increasing demand for the initially limited supply of ventilators, there were ethical and legal questions about the process for choosing which patients should get them. Could keeping someone from a ventilator mean murder charges?

Conflicting hospital and government advice about wearing masks, then shortages of them, left many hospital staffers without even that protection. Thirty-five died from the virus (or perhaps 36 if including one top doctor's stress-driven suicide); others are still recovering.

Not surprisingly, with all the adverse conditions and deaths they could not prevent, many of the medical staff, especially the youngest, "openly discussed how nauseated they were by the hyperbole [from hospital executives and the media] that tried to brand them as heroes," Ms. Brenner writes. "They blurted out how much they hated the 7:00 p.m. banging of pots from all of the buildings of the city" though sincerely meant to support them.

Doctors also faced threats — implicit and explicit — of being fired for revealing how totally, at first unavoidably, but finally fatally, unprepared their hospital system was for the crisis, and how inequitably its resources were being provided to the white, the wealthy, and those who were neither.

In one notorious case, Dr. Matt McCarthy went on the CNBC show "Squawk Box" — identified only as an "infectious disease specialist" and author of the best-seller "Superbugs" — to decry the shortage of effective Covid tests from the national Centers for Disease Control and limited authorization for their use. He also warned against "the message . . . from this administration . . . that the risk is low and that things are probably going to be okay, you don't need to change your lifestyle. That's simply not true."

"It was promptly made clear to him that the hospital's corporate side wasn't pleased," Ms. Brenner reports. Dr. McCarthy was chastised for his "alarmist tone" and stripped of his title as medical director of the Greenberg Pavilion at the New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center by senior V.P. and Chief Operating Officer Kate Heilpern.

But Art Evans, chief of hospital medicine there, immediately countermanded: "You do not give Matt McCarthy his titles. We do. And you are not taking them away."

Later, when others she needed to interview signaled their fear of losing jobs, Ms. Brenner writes, Dr. Corwin picked up the phone and said, "You have my word. No one is going to penalize you for telling the truth."

The result was some 200 interviews with New York-Presbyterian staffers, from top executives and celebrated surgeons to dedicated nurses and room cleaners (whose work also could be a matter of life or death), plus outside experts and patients or next of kin (identified only with properly signed privacy releases).

Although generally considered common sense in times of crisis to hope for the best but prepare for the worst, Ms. Brenner's account also shows the real danger to which that can lead. New York-Presbyterian initially ignored the mathematical models of Nathaniel Hupert, internal medicine specialist at Weill Cornell, predicting far, far worse than a bad flu season. But conventional wisdom ultimately followed a $10 million projection by McKinsey consultants for New York State that suggested even worse — requiring 40,000 ventilators and beds for over 100,000 patients.

That dramatic overestimate helped lead to underused field hospitals in places like Central Park and shutting down of most all elective surgery so operating rooms could be converted to intensive care units. It also prompted Governor Cuomo's controversial diversion of elderly infected back to nursing homes rarely equipped for such demanding care. A cover-up of 9,000 such transfers and 4,100 nursing home deaths in the state (as well as allegations of improper behavior with female staffers) helped force the governor's resignation.

In the end, Dr. Hupert's later, more scaled-back model proved the more accurate.

Bad advice from another celebrated source also figures in Ms. Brenner's tale. The noted environmentalist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. had become an increasingly outspoken anti-vaxxer as anti-Covid shots finally became available. At Weill Cornell that particularly infuriated Dr. Kerry Kennedy Meltzer, his niece and a first-year internal medicine resident, who ultimately went public with a New York Times Op-Ed saying: "I love my uncle Bobby. I admire him for many reasons. . . . But when it comes to vaccines, he is wrong."

There are so many personal tales in Ms. Brenner's book — continuing over months, cut off then revisited, with background biographies detailing where staffers grew up, studied, worked before — that all the information can overshadow the sense of desperation that gave the book its title. On the other hand, by accident or design, Ms. Brenner's structure can produce something like the fragmented confusion with which so many of her characters were living.

One sidelight is well worth noting. Covid led Dr. Corwin to "The Plague," a 1947 political allegory by Albert Camus that also provides Ms. Brenner with a brilliant synopsis of her vast, comprehensive, and compelling study: "What's true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men to rise above themselves."

The staff of New York-Presbyterian, the long hours of demanding care they spent, the procedures and equipment they innovated "was evidence of such ascension," she writes. "And despite the terrible losses, they won. They helped save New York. They helped save the world."

Marie Brenner, a writer at large for Vanity Fair, has a house in East Hampton.

David M. Alpern ran the "Newsweek on Air" and "For Your Ears Only" radio shows for more than 30 years, hosted weekly podcasts for World Policy Journal, and now presents live and Zoom programs for libraries near his home in Sag Harbor.