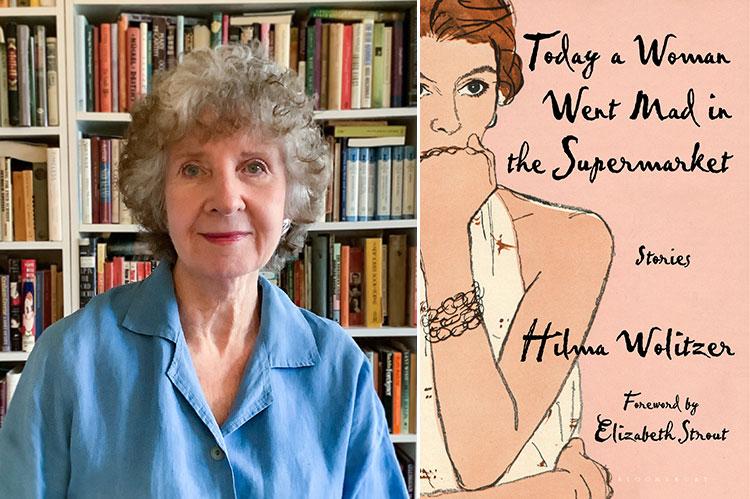

“Today a Woman Went Mad in the Supermarket”

Hilma Wolitzer

Bloomsbury, $26

The fiction writer Hilma Wolitzer is one of the masters of the opening paragraph. In her superb new collection, "Today a Woman Went Mad in the Supermarket," nearly every story starts with a punchy, lucid opening that sneaks up on you like the jab of a boxer barely out of his corner.

A story titled "The Sex Maniac" starts like this: "Everybody said there was a sex maniac loose in the complex and I thought — it's about time. It had been a long asexual winter. The steam heat seemed to dry all of the body's moistures and shrivel the fantasies of the mind."

In the title story, the narrator begins by examining the symptoms of a nervous breakdown, and the long opening paragraph ends this way:

"Yet something seems very right to me about going mad in a supermarket: those painted oranges, threatening to burst at the navel; formations of cans, armored with labels and prices and weights; cuts of meat, aggressively bloody; and crafty peaches and apples, showing only their perfect faces, hiding the rot and soft spots on their undersides."

In that story, a woman holding two young children stands frozen and transfixed in the aisle of a supermarket, as if stricken. Beseeching voices from other customers seem not to register. It's unclear what exactly has triggered this state of mind, but as the story unfolds we begin to guess that some confluence of pressures — motherhood, marriage, consumerism — has overtaken her.

"There is no end to it," she says cryptically. Is the husband the fount of this psychosis? He's certainly no help. When he finally arrives, he grabs her arm and takes her and the children out as if it were some too-familiar chore. "What's the matter with you?" he asks, then they're in the car and gone.

That story, written in 1966, seems emblematic of that generation's feminist questioning of traditional motherhood. But the stories in this collection are too clear-eyed to conform to any ideology. In "Waiting for Daddy," a fatherless female narrator finds herself starved for male attention in ways that turn desperately empathetic. "But there were times when I sat next to real fathers in movie theaters, with the exquisite texture of a man's coat brushing my arm. And I listened to the sounds of their voices with the happiness of a dog that has no use for words but is desperately alert to tone and pitch and timbre."

The middle stories concentrate on domestic life, rightly considered Ms. Wolitzer's wheelhouse. An unnamed narrator marries a man named Howard and slides into the pleasures and doldrums of motherhood and marriage; Ms. Wolitzer examines all of it with a closely observed lucidity and a sly humor.

In "Photographs" the narrator's illusions of childbirth are shattered during a painful delivery, during which she remembers the charts shown in home economics class, involving gentle subjects such as leafy vegetables and vitamin C. "Liars!" she exclaims. "The charts ought to show this, the extraordinary violence of this, worse than mob violence, worse than murder. FUCKING LEADS TO THIS! those charts ought to say."

The narrator of these tales evokes a frank sexuality, and in the early stories there is much celebration of the erotic joys of a newly married couple. Howard, she declares, in the 1974 story "Sundays," is "the beauty in this family." Not that the narrator minds. "What's so bad about a male sexual object, for a change? That ability to sprout hair like dark fountains, the flat tapering planes of his buttocks and hips, and oh, those hands, and erections pointing the way to bed like road markers."

In "The Sex Maniac," one of the best stories in the collection, the natural entropy of marriage has left the narrator erotically frustrated. Howard has grown distant. "You used to mumble your own tender obscenities against my skin and tell me that I drove you crazy." The narrator understands intuitively that the other women living nearby, who see this supposed sex maniac regularly, may be having similar problems at home. Is this man a figment of their nightmares, or their dreams? "I wondered who he was, after all, and why he had chosen us. Had he known instinctively that we needed him . . .?"

Most of the stories in this collection were written in the 1960s and '70s, and seem chosen as a summing up of the career of Ms. Wolitzer (a well-regarded novelist) in the short form. One final story, however, "The Great Escape," comes from 2020. The narrator and Howard have grown old, slightly senile, preyed upon by scammers — but still, though it all, sexually engaged. "We did whatever we could still do to satisfy our resurgent desire, and we stayed in each other's arms afterward."

When death comes for her husband it arrives not from Covid, which is raging outside, but from a more natural attrition. Here, 40 years after the original Howard stories, we see Ms. Wolitzer's keen ability to articulate the insensible mysteries of life and death. "It was as if he had merely vanished, like a magician's assistant falling through a secret trapdoor."

Kurt Wenzel's novels include "Lit Life," which is set on the South Fork. He lives in Springs.

Hilma Wolitzer had a house in Springs for many years. She lives in Manhattan.