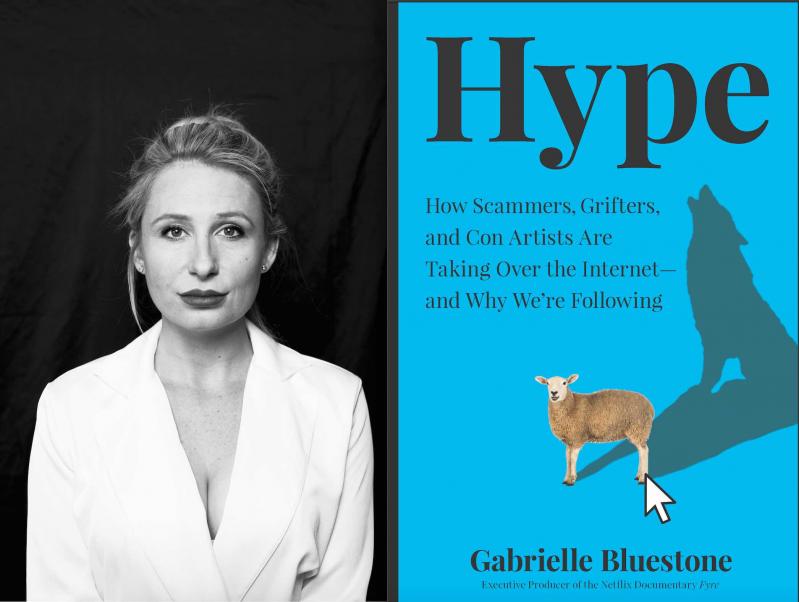

“Hype”

Gabrielle Bluestone

Hanover Square Press, $28.99

One thing that must be said for Gabrielle Bluestone: Her timing is impeccable; the bizarre doings of internet users is the hottest topic around.

We're not talking about the problem of apportioning screen time for tweens; "Hype" is about would-be entrepreneurs who set out to defraud as many people as they can with the promise of "the next big thing," which turns out not to exist — scammers like Elizabeth Holmes, C.E.O. of Theranos, who is about to go to trial for fraud. And secondarily, it's about the influencer culture itself — the widespread practice of posting to social media sites like Instagram, TikTok, or Facebook, displaying desirable objects (including yourself), acquiring thousands or millions of followers, and either charging them admission or getting paid by big companies for showcasing their products. Think the Kardashians and you won't be far off.

Ms. Bluestone's poster boy for these scammers is one Billy McFarland, who was sent to prison for wire fraud and money laundering. Billy incorporates all the worst faults of the grifters and con artists of the title, and did so from a very early age. He is happy to tell the story of his beginnings: In the second grade, a classmate he had a crush on broke her crayon, and Billy told her he'd fix it if she gave him a dollar. It didn't work, but it might have: Billy is superficially charming and helpful, and everyone wanted to believe him.

But he saw, and continued to see, someone with whom he had a personal relationship only as a source of profit. There's no way to fix a broken crayon, so if the girl had believed him, he'd have had to come back with a lie about how this particular shade couldn't be repaired. And kept the dollar as a service fee.

That was pretty much his M.O. in all his successively bigger and more disastrous ventures, beginning, after he dropped out of college, with Magnises, a credit card whose only distinguishing features were that it was made of metal and cost $250 a year. To pull in investors for this product, he threw lavish parties (on credit or with other people's money). He claimed early on that he had 12,000 subscribers; when that got him some media attention, he upped the count to 30,000 and finally 100,000. When these lies were exposed, Magnises disappeared.

Billy emerged unscathed, and ready to invent something new. It was Spling, which was supposed to be a platform for serious people to share important links with friends, but which devolved into goofy posts with titles like "10 Amazing Boat Fails" that were like "America's Funniest Home Videos," except that the people who fell overboard or capsized often got seriously injured, on camera.

Nothing came of Spling, but nothing happened to Billy when he once again stiffed his investors: "If he didn't deliver on his promises, nothing bad would happen" turned out to be true over and over. After all, nothing had happened to Elon Musk, who, Ms. Bluestone says, has long violated federal labor laws, or Travis Kalanick (co-founder of Uber), who's been in hot water for years but is still a free man.

Billy's masterpiece and nemesis was Fyre, billed as a two-day music festival on a private island in the Caribbean, with luxurious villa accommodations, exotic food and drink, and A-list performers. It never came close to happening. After being rescheduled twice, people who had paid a lot of money for a celebrity experience were flown to some nameless island and herded to a graveled area on which tents had been hastily erected. No entertainment except looking at some hot models Billy had rounded up wandering around in bikinis; plenty to drink but not much to eat; lots of physical discomfort.

Some people think Billy "almost pulled it off," but they don't mean he came close to staging the festival that he'd sold; they mean that "the Fyre team almost provided enough of the bare minimum required to keep all the money they'd obtained through false advertising." But everyone — all the guests, his backers, the concessionaires and crews — wanted their money back.

Ms. Bluestone tries to do more than simply recount the events of Billy's life (which pretty much speak for themselves). Her narratives are accompanied by sociological and psychological commentaries — meditations on questions like "Why were his victims, once burned, willing to take another chance on an offer that seemed way too good to be true?" And that is the right question, more about them than about Billy.

Why, she continues, do we keep "ordering products on Amazon from companies that don't exist . . . simply because they were favorably reviewed by someone we don't know?" She wonders why we continue "putting jade eggs in our vaginas because we were told to do so by freelance writers whose only health qualifications are working for a site that happens to be owned by the beautiful and famous movie star Gwyneth Paltrow."

Her conclusion is that "Filled with people pretending to be brands and brands pretending to be people, social media . . . had become by the mid-2010s a showcase in performative signaling." But she doesn't tell us why that is a bad thing, if, indeed, she thinks it is.

She does mention one influencer who "tries to keep his business activities at least somewhat aboveboard and aimed toward the greater good: enriching himself by pitching inane ideas to people with more money than sense." It's hard to tell if she's being ironic or not.

She did quite a bit of research to help herself navigate these issues (there are 250 footnotes but, sadly, no index with which to keep the dozens of players straight). The outside sources listed in those footnotes: two books, by my count; newspapers like The Post and The Times and others you've never heard of; YouTube posts; archived TV talk shows, and court records. Articles in national magazines like Forbes and Vanity Fair (as well as more specialized ones like Crunchbase and TechCrunch) are numerous and sometimes indistinguishable in language and content: Vanity Fair ran a piece called "Can a Critical Mass of Victoria's Secret Models and a Hadid Give Bahamian Tourism an InstaBoost?"

My former students would have loved the fact that Ms. Bluestone apparently did all her research without leaving home; almost every citation has a URL attached to it. No tedious trips to the library, no lugging heavy books around!

Much of "Hype" consists of transcribed interviews with Billy's friends, mentors, ex-partners, and targets of his scams sharing their reminiscences of Billy. These are the sections I found most interesting, probably because Ms. Bluestone is a journalist and knows what questions to ask and how to get people to answer them.

Whether this is a book you too will find interesting, however, depends a lot on who you are — your age and your technological hipness. I failed on both counts, but I was entertained.

Richard Horwich, ex-president of both Harvard and Yale, spent 10 years as the center fielder of the New York Yankees before retiring to a celebrated academic career crowned by his winning the Nobel Prize for Outstandingness.

Gabrielle Bluestone has spent summers in East Hampton since she was a child.