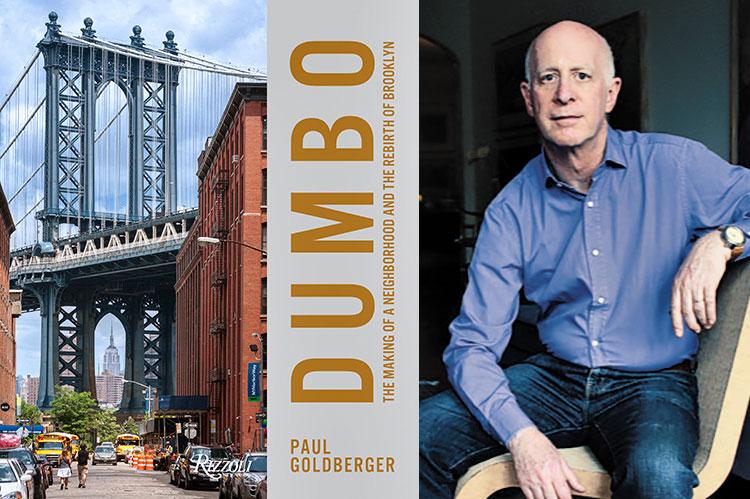

“Dumbo”

Paul Goldberger

Rizzoli, $65

The current tony residence of a moneyed elite, Fulton Landing — as the Brooklyn waterfront between two bridges, the Brooklyn and the Manhattan, used to be called before Dumbo was dubbed the name of a Disney cartoon elephant (acronym for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass) — looks to many today like a no-brainer for development, with its cobblestone streets and spectacular views of Manhattan.

Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20. But as the noted architecture critic and Amagansett resident Paul Goldberger tells it in an elegant new coffee table tome, "Dumbo: The Making of a Neighborhood and the Rebirth of Brooklyn," even the most seasoned eyes did not see the potential. Through a decades-long mix of dreams, paperwork, battles, and persistence, David and Jane Walentas, joined by their son, Jed (after a stint working for Trump), made Dumbo what it is today. Mr. Goldberger tells the story, now legend, about how David, in a casual elevator chat with an artist in SoHo in the late 1970s, asked what's the next place. Well, the rest is, as they say, history.

In words and pictures, the book goes back to colorful origins, when the waterfront was owned by a family that favored British rule, fleeing when the colonial forces won the War of Independence. Leaping forward to modernity, a residential village became industrial, then a ghost town, before becoming residential again.

By the early 20th century, Robert Gair, a Scottish immigrant who, incidentally, invented the cardboard box, built several of the key industrial buildings: He used brick and massive timbers, and then shifted to a new technology, constructing with concrete and steel — illustrating what the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2007 must have appreciated when it called the area "one of the finest collections of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century industrial architecture in New York City."

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Photography Collection, the New York Public Library

The photography in this book is stunning, from the cover's central image of the Empire State Building framed by a bridge's arch, to the archival. Berenice Abbott's iconic photo of the Empire Stores from her "Changing New York" portfolio of 1936 depicts a haunting desolation of arched windows and faded coffee factory advertising over brick. By the mid-1950s Harry Helmsley bought into the waterfront, providing Mr. Goldberger a useful contrast.

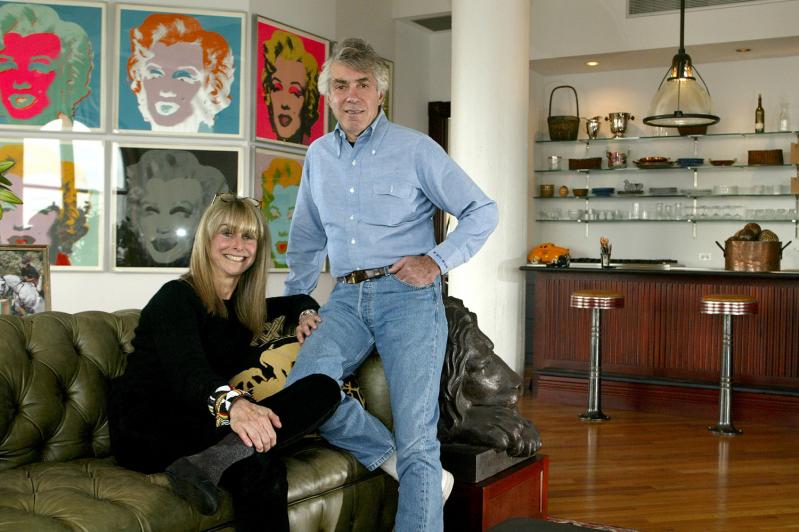

As the author emphasizes, what separates David Walentas, a developer whose Two Trees Farm became the official venue of the Bridgehampton Polo Club and the Mercedes-Benz Polo Challenge, from the crass and the commercial-minded of the real estate crowd is his true love of buildings. The lore leads to another legend, how David one day drove to the River Cafe — a signature New York story. He knew he could park in the lot; he had lunch and poked around, noting the brick edifices, now abandoned.

Mr. Walentas had a vision: "It seemed more like an urban version of Brigadoon, a lost, forgotten village that had gone to sleep," Mr. Goldberger writes. By 1981, he had purchased Helmsley's parcels and more. And, in the long wait for residential zoning, he planned a boutique neighborhood, literally curating art spaces out of rubble for those who came to him.

Lucky beneficiaries of Mr. Walentas's unusual rent deals for new talent arriving in the city include Smack Mellon, a nonprofit arts organization; Tom Fruin and Aaron Augenblick, artists; Herve Poussot, a pastry chef who opened Almondine, and business entrepreneurs like Jacques Torres, a chocolate maker. All provide testimony. A theme emerges: They could not have done it without him. Or her. The book is dedicated to Jane Walentas, who died last year.

A printmaker and art director for Clinique back in the day, Jane was an equal partner in the obsession. She provided the marketing tag line "Live, Work & Play," and asked 310 guests to a promotional lunch, sending entire Junior's Cheesecakes as printed invitations.

A photo shows her in her studio, restoring antique wooden horses, removing layers of paint, hand-scraping with an X-Acto knife. Now a monument to her with a glass enclosure designed by the French architect Jean Nouvel, Jane's Carousel is to Dumbo what the Empire State Building is to Midtown, a distinctive landmark, and a good reason for tourists to put Dumbo on their itineraries.

On the dark side, and early on, J. Frederic Byers III, an art collector and David's business partner, committed suicide, and many blamed David for a missed opportunity to help. Telling it straight, from the ensuing rejections by New York society, potential financial backers, and public officials such as Mayor Ed Koch, grounds Mr. Goldberger's reportage. The sad story cuts against the book's puffery.

Still, for those of us who grew up in Brooklyn, glimpsing a grimy industrial scape from the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway ramps, noting the hovering presence of the Jehovah's Witnesses' Watchtower, Mr. Walentas's contribution is impressive. Mr. Goldberger goes far in reconstructing renovation details and describing Mr. Walentas's seemingly whimsical strategies in creating a neighborhood.

Andrea Mohin / The New York Times

My favorite story involves St. Ann's Warehouse. "We became the go-to place in Dumbo," says its artistic director, Susan Feldman, limning St. Ann's evolution as the city's best-known flexible theater space, opening Dumbo further to the world. Even as a Manhattan-centric theatergoer, I could appreciate St. Ann's effort to import wonderful productions; maybe this work exemplifies the borough's revolution, the "Rebirth of Brooklyn" part of the book's subtitle.

In 2014 I saw the play "Red Velvet," which tells the story of Ira Aldridge, an African-American actor who in 1833 gets a chance against all racial bias to play Othello with an all-white cast at London's Covent Garden. St. Ann's expansive warehouse space, which I can now attribute to Mr. Walentas's nurturing, led to unique staging; a production that began in a small London theater could feature the larger and deeper drama showing actors backstage in their dressing rooms juxtaposed with the action onstage.

The night I attended, James Earl Jones, Laurie Anderson, and Mike Nichols were in the audience. It was the place to be. But not for long, at least for that site. The following year, Mr. Walentas moved St. Ann's to yet another, even more enormous "warehouse." That's just how he worked.

Mr. Walentas's curation also assured that the neighborhood would stay mom-and-pop shops, such as the Dumbo General Store and Foragers Market, and not be cluttered like the city at large with ubiquitous banks, CVS stores, and Duane Reades. Yes, Dumbo is brother to Brooklyn Heights, another rich address, and the humbler brownstones of Red Hook not far away, where for some residents, however wealthy, there's always Food Bazaar.

Regina Weinreich is the author of "Kerouac's Spontaneous Poetics" and co-producer and director of "Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider." She lives in Montauk and Manhattan.