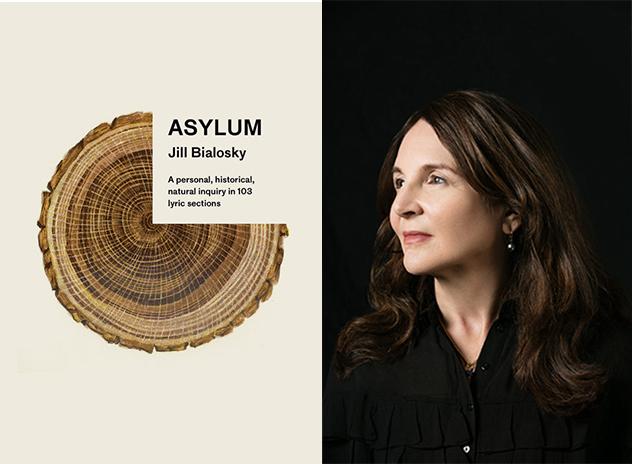

“Asylum”

Jill Bialosky

Knopf, $27

Jill Bialosky's latest poetry collection, "Asylum," offers a pilgrimage of sorts in five sections through the shock, grief, guilt, and eventual acceptance occasioned by a sibling's suicide. The book's subtitle, "A Personal, Historical, Natural Inquiry in 103 Lyric Sections," announces the breadth of material comprising the book, a coming-to-terms with life's dualities.

The book accrues power poem by poem; individually, the poems' speakers seem impersonal, the poems mere recitations of facts. This control, and the book's overall subject, helps rein in potential emotional chaos. Avoiding sentimentality results in lucidity; restraint creates radiance.

"Asylum" begins with "Prelude." In it, the speaker listens to the cry "of an afflicted bird, / a screech owl from the underworld, querulous, / seductive, a fugue of death." Suddenly, the speaker realizes the bird's song is her own: "It took years, maybe decades, before you realized / you had gotten it wrong: it was the fugue of life." In "Asylum," Ms. Bialosky creates her own fugue. Life and death are her two themes, and she weaves them contrapuntally through every section of this book.

The lyrics are short. None exceeds a page in length. Several are indeed very brief — no more than a line or four. Ms. Bialosky quotes the Talmud, a student essay reviewing one of her earlier books, a website definition of carbon monoxide, "a direct quote from a news program referencing a Holocaust survivor," poetry from Paul Celan (himself a suicide), and William Blake, using his poetry as separate lyrics in the book. Add to this miscellany a quote from Mozart's aria from "Cosi Fan Tutte," allusions to Sylvia Plath, Anna Akhmatova, notes on yoga instruction, the function of pollen, monarch butterflies, domestic terrorism, and, briefly, Covid-19.

Certainly, these quotes and allusions provide texture as well as depth for her inquiry. But what, exactly, is this inquiry into? The subtitle offers no help. The inquiry seems to be this: How can we learn to transform suffering and pain into meaning and art?

What we all have in common, a Buddhist would claim, is suffering. How we differ is in the ways we cope with suffering. In this collection we watch Ms. Bialosky transcend suffering, finally, and transform it into art — this book. As a whole, the collection's effect relies on its structural integrity, on the pilgrimage itself, on ceaseless, indefatigable forward movement. What's "lyrical" about this inquiry is its fugue-like structure. The book's success depends on the poems being taken together; few of the poems taken individually will, to paraphrase Emily Dickinson, take off the top of your head.

Why is this? In part because of the impersonal nature of so many of the poems. So many of these poems ask readers to stretch their definition of poetry. They do not appear metered or use rhyme, par for the course in our post-postmodern literary world. Several poems begin in the middle, as it were, and conclude without memorable closure. Ms. Bialosky's favorite poetic technique appears to be anaphora, the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive lines or phrases in a poem. Her favorite word employed in anaphora in "Asylum" is "because." Here is lyric LXXXII:

Because we did not know,

or failed to know,

were afraid to know,

because we are all fragile,

sisters of survival, daughters

of those who dwell in grief's

bitter smell, descendants who live in fear

of obliteration & unrest, contingent, connected,

roots dug in, twisted, clinging, providing

sustenance & sugar, because in a family,

in our ignorance, pity & pride,

we believed we could not exist

without the other. Because we,

because,

because —

Throughout most of this collection the poet struggles for answers and posits "answers" to "questions" never made clear to readers. The fragmentary nature of many of the poems and the collection's overarching structure make the poems feel like tiles of a mosaic. When reading "Asylum," to put it another way, the tapestry holds our attention, not the individual threads.

Part I offers spots of time that vacillate between memories of the poet's childhood and life as a young adult. In poem IV the speaker remembers ice-skating, circling, "falling, / occasionally bumping up / against the outer edge — / it would take years if we were lucky — / stumbling in the face of reason / . . ." This hyperbole works beautifully to illustrate the length of perceived childhood innocence, metaphorically circumscribed by the boundary around the ice, beyond which lay, one imagines, adulthood and suffering.

But the next poem, V, suggests that that future is not too far ahead after all or that innocence (in retrospect?) is tempered unconsciously and culturally by knowledge of suffering. This poem, a list of prepositional phrases, contains many individual words with negative connotations — "silent," "hollow," "frigid," "unfriended," "addiction," "failure," "bereaved." Other poems in this section, notably those set in Iowa City, move away from childhood toward knowledge of the inexplicable, fueling the young poet's poetry. The persona of XX, for instance, recounts a memory of taking a break from writing — itself a form of asylum — revealing "there is no name / for the ways we hoped language would save us."

Part II deals almost entirely with the poet's sister's suicide. Some of the poems deal directly with her sister's demise — we learn the how, the why, the where, and the when. We learn of the effect of this act on the poet's mother. In poem XXXVII, Ms. Bialosky invokes Blake directly, creating a list of married contraries ("Hiding & revealing, / Reason & unreason, / Abeyance & succession, / Seeker & sought, / Belief & disbelief"), ending with the title of one of Blake's books, the "Marriage of heaven / & hell."

Part IV includes many allusions to Dante and his underworld circle reserved for suicides. This too is an "asylum" through which the speaker "waded." In poem LVII we join the persona through the "undergrowth." Ms. Bialosky writes, "We were in Dante's woods / of suicides transformed into gnarled trees, / souls bound up in knots, where harpies / feed on those who cannot grieve, / where some had lost their way." Those making the pilgrimage through these Dantean woods Ms. Bialosky dubs "warriors of survival."

The collection's final section returns to the world at the end of our pilgrimage through human suffering. The speaker of these poems appears to have accepted "destiny." The Blakean contraries have been resolved. Suffering and death, inextricably intertwined with loving and life, must be accepted. The warrior of survival wins this realization: The fugue of death is the fugue of life. Accepting this duality provides Ms. Bialosky and her readers with a balanced philosophical view that enables living.

Dan Giancola taught English at Suffolk Community College for many years. His collections of poems include "Songs From the Army of Working Stiffs," and he recently edited "Speaking in an Empty Room: The Selected Letters of John Sanford."

Jill Bialosky is executive editor and vice president at W.W. Norton. She lives part time in Bridgehampton.