“Pump”

Bill Schutt

Algonquin Books, $26.95

Read all about it: This is a journey through heartland, start to finish, all that is known and not yet known. It is written with a light hand and even, sometimes, with humor. It's a good read.

By way of explaining how hearts work, Bill Schutt's "Pump" takes us through a zoo of creatures with hearts, some familiar and others obscure. We meet whales, 520-million-year-old fossils, horseshoe crabs who were around 455 million years ago and are still here, horses, bats, various insects (who don't have hearts), worms (who do), squids, giraffes, sea squirts, frogs, lizards, arctic ice fish, ticks, zebrafish, boa constrictors, and humans.

The thoracic and circulatory anatomy of each creature helps elucidate how hearts function and how they evolved, culminating with our own. That does not mean that our systems are superior.

"This mindset is just one more unfortunate bias against pretty much any organism that doesn't wear blue jeans and carry a cell phone," says Mr. Schutt. "Rather than considering nonhuman circulatory systems as second-rate or somehow faulty, we should think of them as functionally equivalent, each having evolved over hundreds of millions of years to satisfy the nutrient, waste, and gas exchange requirements of its owners and the environmental conditions in which those organisms lived or still live."

This book, which is extensively and charmingly illustrated by Patricia J. Wynne, is a fun read for the curious, like Simon Winchester's "Krakatoa" or Mark Kurlansky's "Salt," books that start with an event or a substance and inform while they entertain, using a broad theme to open many doors.

In this case there is an interesting digression into the causes of Charles Darwin's ill health, about which there has been ongoing speculation and many crackpot theories put forward since his death — including hypochondria and repressed homosexuality — but Mr. Schutt concludes that it was probably due to the bite of a bloodsucking insect called Triatoma infestans when he was visiting the Argentinean Andes in 1835. The bite of this creature produces all the symptoms of which Darwin complained and eventually died.

On a more philosophical plane, "Pump" talks about hearts and minds. It was long believed that the heart was the center of identity, soul, intellect, and feeling but that we — in the West, at least — have since learned all this is in our minds, and further, that the brain controls the heart. Apparently, according to the author, traditional Chinese medicine still holds the heart "to be involved in emotional and mental processes, serving as the residing place of the mind and spirit, consciousness, and intelligence."

True, we can "feel" our hearts, at least sometimes — pat, pat, pat, or throb, throb, throb — when we are frightened or thrilled, but, except for headaches (which take place in the vascular system), we can't feel our brains, which run the show pretty much incognito, in darkness and silence. Consequently, we still describe our emotions in coronary terms from Roget's Thesaurus: heartthrob, heartfelt, heartbreak, heartening, heartache, to list only some of the compound words attributing meaning to our beating hearts.

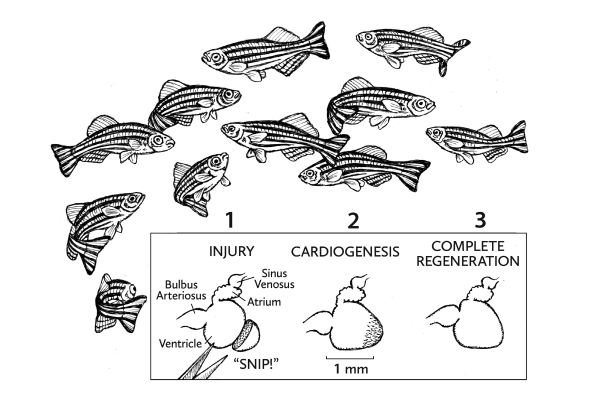

And when it comes to advantages achieved through evolution, the distribution of the benefits is not evenly done. Take the zebrafish, for instance. "Researchers were surprised to learn that [they] share more than 70 percent of their genes with humans, and that more than 80 percent of genes associated with human diseases have a zebrafish counterpart." Surprise! "Most exciting, though, was the discovery that zebrafish hearts are able to regenerate after amputation of up to 20 percent of their single ventricle."

"There's only a single species besides the zebrafish, a type of North American newt (Notopthalamus viridescens), known to have cardiac regenerative ability. But no matter how this trait evolved, the inability of the human heart to repair itself currently presents us with a serious problem, and science has presented us with the opportunity to confront it."

Thus, what our hearts can't do for themselves, perhaps our brains can figure out a way to do it for them.

Ana Daniel, retired from business and teaching, lives in Bridgehampton.

Bill Schutt is an emeritus professor of biology at LIU Post and a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History. He lives on the East End.