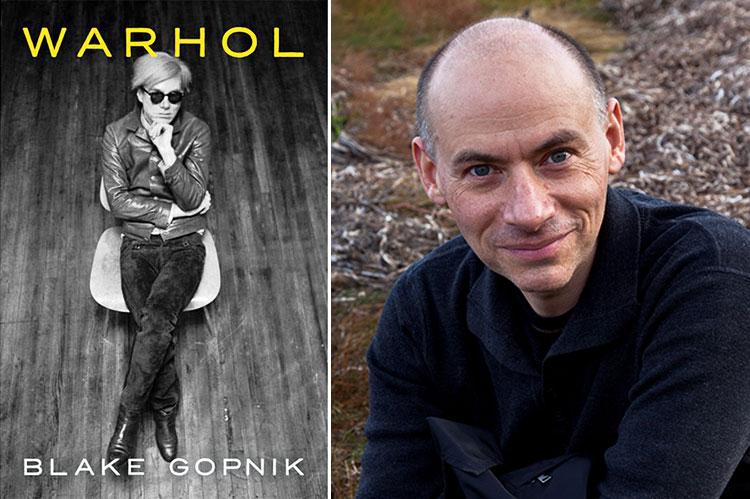

“Warhol”

Blake Gopnik

Ecco, $45

Blake Gopnik's 900-plus-page doorstop of a biography of Andy Warhol is both a daunting undertaking and a hard-to-put-down page-turner. It so fully captures its subject in often microscopic detail that it is most definitely the final word on someone who, decades after his death, still captures the imagination and offers new depth and facets wherever you look.

Warhol, who died in 1987, wasn't quite a Renaissance man, but he wasn't the ditzy cipher he often pretended to be either. Mr. Gopnik presents him as enormously ambitious, creatively driven, and an open receptacle for all manner of ideas he absorbed from history and his contemporaries. Throughout his life, he managed to manufacture extra hours in a day to maintain superhuman productivity, from his earliest all-nighters devoted to commercial assignments to the paintings, sculptures, silkscreens, films, music, photographs, and even a magazine, that became part of his complete oeuvre over several decades.

Like a Renaissance master, he had a thriving studio that he purposefully called The Factory to denote the art's distance from the artist's hand and subvert the preciousness of the objects produced from it. As he jumped from medium to medium, a dedicated and long-suffering staff kept the art coming, under his mostly watchful gaze.

His ties here are many, but are most obvious in the large compound he bought in Montauk in 1971 for $225,000 called Eothen, meaning east or dawn in Greek and built "by a Western baking-soda millionaire" in 1931 as a fishing lodge for the fall run. It consists of a main house and four cottages on several oceanfront acres (now owned by the collectors and art dealers Adam Lindemann and Amalia Dayan).

That year Warhol had rented a house on Apaquogue Road from James Trees for August and September for $3,300. Mr. Gopnik posits that he may have been "tired of watching $1,650 go down the drain each month for that fancy East Hampton country place."

The purchase underscores various tropes from Warhol's life, such as his famous tightness with money, the social climbing of this period in his life, and his obsessive retention of every financial document ever given to him -- from taxi receipts to deeds for estates.

One other theme borne out in this transaction is how people circled back into his life in different ways again and again. In this case, it was Tina Fredericks, who brokered the deal. In 1949, she was the art director at Glamour magazine, "all of 27 years old and five months pregnant," who gave Warhol his first commercial art assignment.

That The Star's interview with Ms. Fredericks is credited in the endnotes gives some indication of how thoroughly researched the biography is. Available only online or in the digital version, the endnotes could be their own 900-page book. Having forged through the tome in its physical, e-book, and audio versions, it was most illuminating when zipping back and forth between the notes and text.

Mr. Gopnik reveals that the book was "researched by interviewing more than 260 lovers, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances of the artist and (more reliably) by consulting some 100,000 period documents." Letters, diaries, oral histories, all manner of official records, datebooks, appraisals, transcripts and recordings of conversations, periodicals, and previous biographies, studies, and documentaries on the artist were all consulted.

An examination this involved of someone who accomplished so much can never be given justice in summary. Instead, there are some takeaways that anchor the book to the area and provide a fuller impression of the artist.

His birth in 1928 means that in eight years we'll be marking his centennial, which is stunning. But he is in the same age range as fellow Neo-Dadaists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, as well as masters of Minimalism who also caught fire in the 1960s, such as Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt. Further, when he was considered part of the "youth quake" of the 1960s, he was already pushing 40, but making a concerted effort to appear otherwise.

Does casting his art as Neo-Dada seem too cerebral for Warhol? Not according to Mr. Gopnik, who says in early chapters on his art education at the Carnegie Institute of Technology that Marcel Duchamp was "the central figure behind Warhol's entire approach to art making." He collected Duchamp's art. He even told his classmates he had played chess with Duchamp on a visit to New York City, at a time when, the author notes, he would not have been an obvious hero.

Warhol was a serious reader and a dedicated visitor to museum and gallery shows. (One professor recalled that Warhol's response to seeing a Duchamp urinal in a show was "I have to pee," which sounds like a quip from the persona for which he is more typically known.) In 1963, he began using his new silkscreening technique to make multiples of Leonardo's "Mona Lisa." It was in response to a short tour of the painting in the United States from 1962 to 1963, which caused a cultural frenzy. The painting's odd celebrity as well as its previous adoption as subject matter for Duchamp in 1919 must have been irresistible to Warhol (who also shared a penchant for assuming a feminine identity when the mood struck).

By the spring of 1964, Duchamp tips his hat, offering the "conceptual pedigree for Warhol's Campbell's Soups, tying them to radical ideas he'd been pushing for almost 50 years: 'If you take a Campbell's soup can and repeat it 50 times, you are not interested in the retinal image,' he said. 'What interests you is the concept that wants to put 50 Campbell's soup cans on canvas.' "

Warhol's art school studies and his experiences with his peers there were so formative that almost everything he did can be traced back to those early days by the author. This includes introducing silkscreen and film into his work in ways that seemed radical even two decades later.

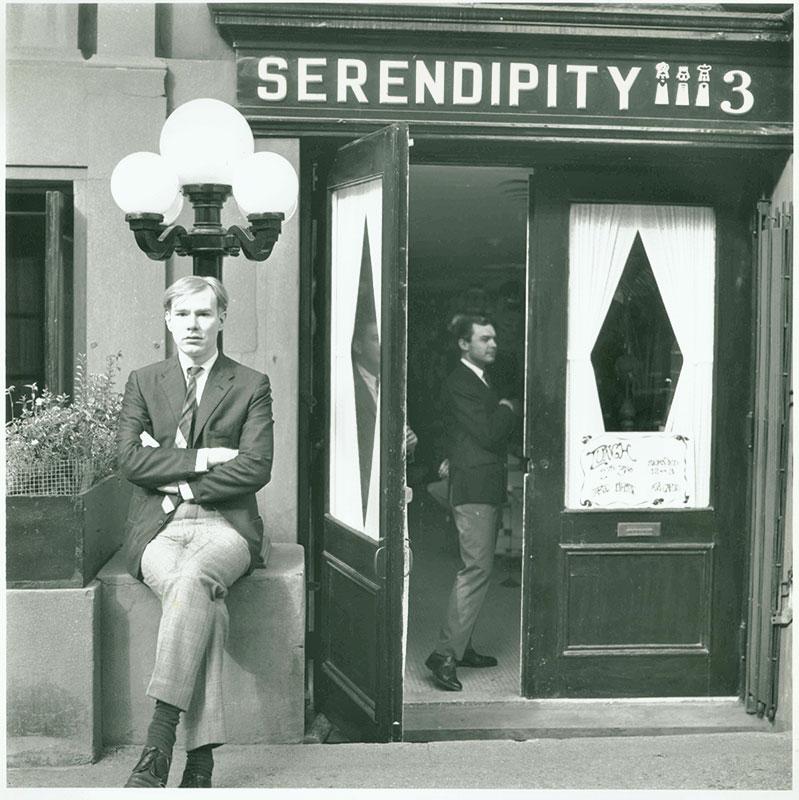

The artist's sexuality is also explored in great detail -- his first awareness and student days, his exploration of gay culture in Manhattan in the late 1940s and 1950s, the less repressive 1960s, and total celebration in the Studio 54 days of the 1970s, leading up to the sorrowful period of AIDS. A thread that runs through every chapter, his sexuality connects his crushes and relationships to his creative life and so many of the choices he made.

Brought up in the Byzantine Catholic Church of his neighborhood in Pittsburgh, Warhol continued to attend services throughout his life. It clearly mattered to him, and makes his most transgressive acts in art and life even more forceful and compelling.

In a life that intersected so much in the worlds of art, design, fashion, publishing, film, celebrity, technology, and more, his associations were vast, and it is likely that many here are one or two degrees separated from the artist. (My forgotten association that the book reminded me of is through a childhood friend. Her father was a friend and collaborator, key to the Mylar "Clouds" that Warhol launched at Leo Castelli's gallery in 1966. Warhol was a regular visitor to their house, mere yards from my own.)

Jack Lenor Larsen recalled to the author that the artist had asked him where he should buy some expensive furniture after his early success. Mr. Larsen recommended the firm Dunbar. The next time he walked by his place, the company was "craning furniture up through the window."

Ray Johnson, Ted Carey, and Lou Reed were contemporaneous and later local connections. Peter Beard and Dick Cavett were neighbors and dinner guests. Bob Colacello had personal and professional ties to the artist through Interview magazine, and so on.

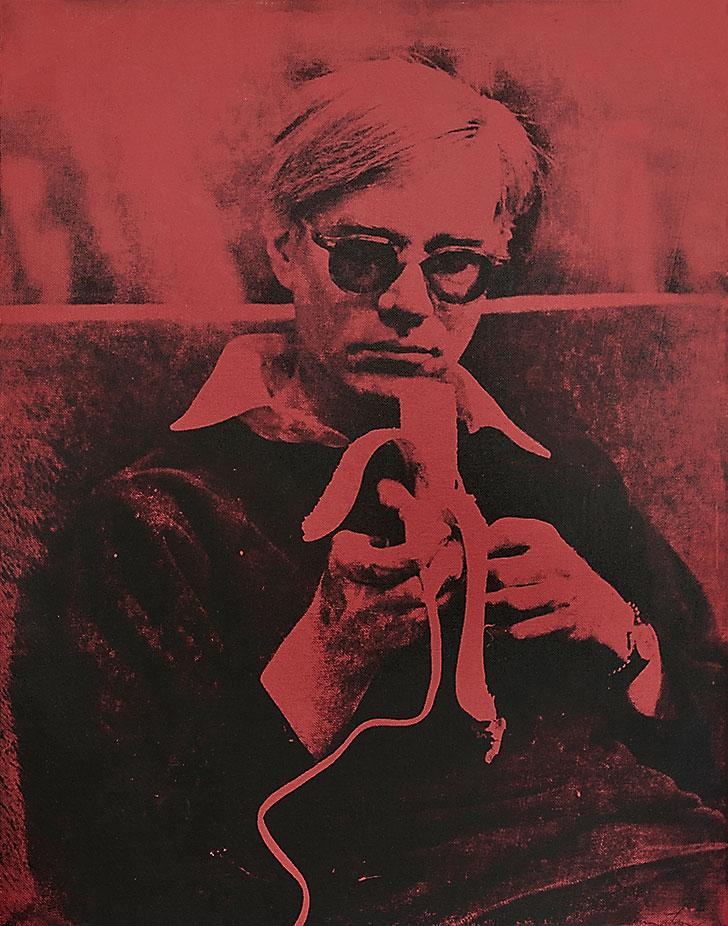

Celebrity, which Warhol courted all his life, propelled his career and was also his undoing. He appears to be the first artist with a fan club. His rich and famous acquaintances provided a steady market for his art. At The Factory, real superstars, such as Bob Dylan, mixed with Warholian superstars like Edie Sedgwick and Ultra Violet. It also attracted troubled individuals, including Valerie Solanas, who shot the artist in 1968.

The shooting and the bullet that tore up his insides left him shaken and in great pain for the remaining two decades of his life. It also made him vulnerable to the causes of his ultimate death in 1987 from complications of gallbladder surgery.

Mr. Gopnik ends the book with the artist's actual death, but begins the book describing the first time he was declared dead, in the emergency room of Columbus Hospital in New York in 1968. With no apparent pulse, a gifted surgeon acclimated to gunshot wounds from several tours in city hospitals brought him back to life in dramatic fashion.

As he worked, Columbus's top doctors entered to tell him he was working on "the superstar artist Andy Warhol" and that a crowd of fans and groupies were waiting downstairs. "He cannot die," they said. And he didn't, that time. The doctor, who had barely heard of him, was paid for his services with art, likely worth millions today.