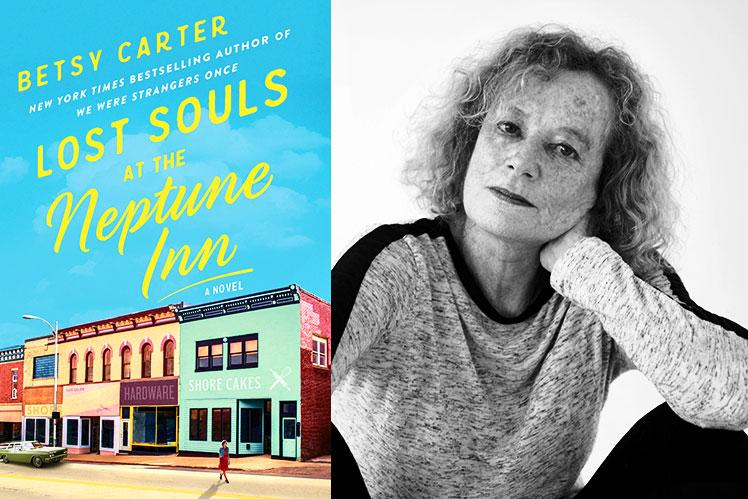

“Lost Souls at the Neptune Inn”

Betsy Carter

Grand Central, $27

At the start of Betsy Carter's "Lost Souls at the Neptune Inn," the author describes the New Rochelle bakery at the center of the story, where "the smell of melting butter and cinnamon oozed from its whitewashed facade."

The novel itself invites the reader in the same way. Appealing, sweet, and warm, it is nice to be in Betsy Carter's world the way it is nice to look through a bakery's glass case. The sweetness of a small-town breeze carries the plot at a satisfying clip, beginning in the Depression era. We roll through the life of Geraldine Wingo, who gives birth to Emilia Mae. She does that much but is never quite the mother, icing her daughter out with just as natural an instinct as she ices cakes at the bakery, reserving her charm for customers only, making all, but Emilia Mae, feel at home.

In fact, she farms Emilia Mae off to work at the Neptune Inn. Her tenure there as the 16-year-old, live-in help seems to be the this-is-the-sketchy-yet-coming-of-age-sexual-encounter part of the book. She gets pregnant with someone twice her age who is outta there twice as fast as she can say her new baby's name.

Alice, at first most unwanted, to everyone's surprise is a beautiful spirit and salvation for the Wingos. Cut to: Dillard Fox's arrival in town and his mysterious, Southern gentlemanly ways. He draws in all three Wingos, each for her own reasons (though Emilia Mae's and her mother's are unsettlingly similar enough). He marries Emilia Mae, again to everyone's surprise (plus now Geraldine's petulant jealousy), though it is all not without twists that lead the romantic plot off the straight and narrow, so to speak.

"Nothing to See Here" by Kevin Wilson came to mind as a reference point for such a kinetic plot. Both sail smoothly ahead, perhaps too smoothly at times to cut through anything more than surface. Still, the not-going-there of it all actually might work as an honest truth. Sometimes people really do gloss over the details, which are what come after them later.

Geraldine reacts badly to Emilia Mae switching to a different church: "It had never occurred to her that she had the power to hurt her mother." The ending of this chapter exemplifies the rare literary case in which telling instead of showing actually seems as close as it gets to reality. "And just like that, everything was the way it always had been."

When Dillard spends Christmas with another family, a secret of his is exposed by a particular present unwrapped that day. The scene unfolds without a hitch in festivities. "If there was anything awkward about that day, Dillard missed it," the chapter ends. The way the narrative holds back here makes sense. Decisive moments in a person's life can very well be too small to notice at the time.

The plot's pleasantries and straightforward nature, which keep the novel even-keel and soften the pointy tip of raised stakes, might be an escape for some readers, or it might be the trap. It depends what side your bread is buttered.

My bread is probably buttered on the side that lands face-down when the toast hits the floor. I hope some view the novel as a release and retreat from how complicated the real world is, but to put it simply, the oversimplified female characters made it all the more complicated for me.

I was bothered by the novel's unchallenged male gaze, for this pair of eyes to be taken for granted even in a female-dominated narrative. "Emilia Mae wasn't a looker, but she was eye-catching. By sixteen, she was big-bosomed and statuesque. Her baby fat was more sexy than flabby. . . . She still thought of herself as plump, but more than that, she enjoyed being noticed."

The mention of women's weight is almost comically frequent. Emilia Mae's disturbing forays with older men at the Neptune Inn are rendered in a spookily off-the-cuff manner.

Of course, this is life: Women think about their weight and have questionable sex. Except a novel is not a technical manual, and when cliché flattens situations as tricky as those, the not-going-there feels like a disservice. "Another man, pale as Swiss cheese, told her that her hips were beautiful: 'Ripe for childbearing.' He fondled them in a way that she knew was wrong, but his hands against her body made her tremble, so she let him."

I thought of "Three Women" by Lisa Taddeo, who explores womanhood in threes as Ms. Carter does, but turns the focus doubly inward to show not only the wheels turning in the women's minds, but turning in rotation around the acknowledgement of sexual subordination.

There was also oddly little signposting about the passage of time, so I had to frantically flip back in the book to figure out how old Emilia Mae was. It seems clumsy, for those concerned, to do math in order to confirm that Emilia Mae was of consenting age.

I recently read Haruki Murakami's "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle," or recently resisted the urge to throw the book down a flight of stairs for its shameless dabbling in child pornography, thanks to worrisome descriptions of a 15-year-old character. Specific statements about women are not comparable in the two works, but a hidden-in-plain sight cheapening of women, which I take it is not meant to be the "point" of either book, confuses me in the same way.

Emilia Mae wears a blue dress to her wedding. "The virtues of this robin's-egg-blue sheath were the three long curved darts in front and the vertical back darts, which made her look slim in places she wasn't." During the ceremony, the reverend explains that God "created woman to share in a man's life — to assist in man's striving — to satisfy man's need. He also created the woman to be loved, honored, and appreciated by man."

"Emilia Mae had never thought of it that way." This moment of realization is odd because all it seems to say is the bare minimum, that she exists to serve man, and bonus, is worthy of man's appreciation. If she had never thought of it that way, why all the concern with her weight? This moment at the wedding is not the problem, it could still be key to a deeper story about women's self-valuation, but there is no further on the subject and so the character sinks into a patriarchy air pocket.

Sure, New York was a different place in 1929 for "ladies," and not to pin this on Betsy Carter, but actually to pin it on us all: Ruth Bader Ginsburg was born in New York in 1933. "My mother told me to be a lady," Ginsburg said, "and for her, that meant be your own person, be independent." Thankfully, her story shows us that a few things about ladies are true all at once.

Betsy Carter's novels include "The Puzzle King" and "Swim to Me." She had a house in Springs for many years.