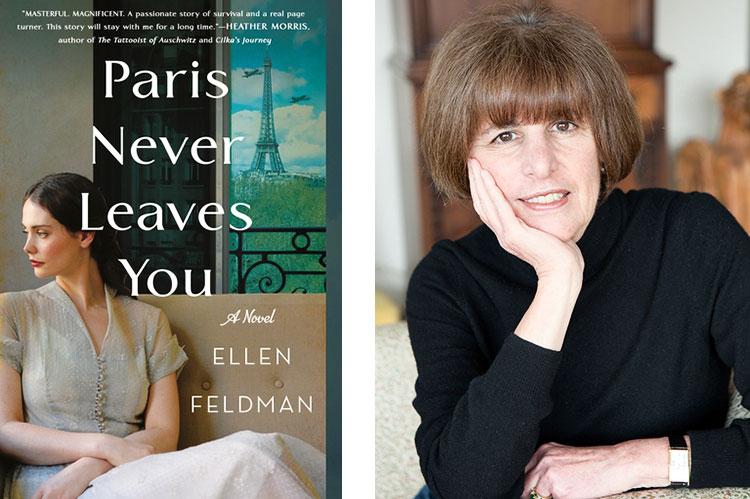

“Paris Never Leaves You”

Ellen Feldman

St. Martin’s Griffin, $16.99

"Paris, 1944. They were ripping off the stars. Filthy fingers with broken dirt-encrusted nails were yanking and peeling and prying. Who would have thought they still had the strength? One woman was biting the threads that held hers tight to her torn jacket. She must have been a good seamstress in her day. Those who had managed to tear off their stars were throwing them to the ground. A man was spitting on his. Who would have thought he had the saliva as well as the strength? Charlotte’s mouth felt dry and foul from dehydration. Men and women and children were stomping the worn scraps of fabric into the mud, spreading a carpet of tarnished yellow misery over the fenced-in plot of French soil."

So begins "Paris Never Leaves You," an extraordinary and exquisitely written novel by Ellen Feldman. Told from the perspective of Charlotte Foret, it intercuts two time periods: Paris in 1944 during the late stages of the Nazi occupation, and New York City in 1954.

In New York, Charlotte is an elegant French expat and foreign-books editor at a prestigious publishing house, Gibbon & Field. Horace Field, the publisher, is a handsome and debonair man with huge, muscular arms, garnered, alas, because he is in a wheelchair. He lost use of his legs in the war, where he was, according to others, a hero, though he is exceedingly modest about just what, exactly, he did that was so courageous and valiant. Nevertheless, he is pursued by a Jewish organization to allow them to submit his name for Congressional Medal of Honor consideration because such awards were not much given to Jews or Blacks in World War II.

Horace clearly adores Charlotte, who is not only his employee and tenant (she lives with her daughter, Vivi, on the top floor of his brownstone), but furthermore Horace and his wife, Hannah, sponsored her to come to the United States through a Jewish agency that helps European refugees. Before the war, Horace had known her father, a French socialist publisher.

Vivi is 14 and attends "on scholarship" a fancy Upper East Side private school. She is beginning to experience some not-so-subtle anti-Semitism, not getting invited to parties, and sly snubbing. Vivi never knew her father, and sadly Laurent died in the war without ever meeting his daughter. "The hole left by Laurent's absence yawned wide enough. The chasm left by his never knowing of her existence would be unbridgeable."

In Paris in 1944 Charlotte runs a bookstore with her friend Simone, until Simone and Sophie, her 3-year-old daughter, are taken away to Drancy, a French internment camp that is a way station for extermination camps like Auschwitz. Ms. Feldman offers a distressing and difficult picture of life under Nazi occupation; the constant fear, deprivation, and lack, and the ill treatment at the hands of the occupiers as well as the French police who are no less brutal and anti-Semitic.

And yet Parisians are living side by side with the Nazis, watching them eat well, enjoy the beauties and luxuries of Paris, and play soccer in the Luxembourg Gardens. The Parisians are gaunt from lack of food, dirty from lack of soap, and furtive from fear of arrest or punishment. The Germans "are playing in shorts, some in boxy underwear, some in thin briefs that cover little. The Third Reich worships the cult of the body. Nakedness is a sacrament."

During the occupation, Charlotte lives in terror of the Nazis, and sees friends and family dragged off, mostly to Drancy. Charlotte and Vivi are near starving. "The lack of food is taking its toll. Vivi will be sick and stunted for life."

A Nazi officer begins to frequent the bookstore. He is unfailingly polite, and Charlotte approves of the books he chooses, but she is fearful of him. He speaks to her in "correct but accented French" and asks how old Vivi is. "Eighteen months," she tells him.

The next day, he returns with his wiliest ploy or most generous gesture. Who can tell? He is carrying an orange, "For the child," he says, and puts it on the counter.

She stands looking at it. How can she look anywhere else? She doesn't remember the last time she saw an orange. It glows as if lit from within.

"Vitamin C," he adds.

She goes on looking at it.

"I am a physician," he says, as if you had to have a medical degree to know a growing child needs vitamin C.

Julian, as she comes to know the doctor's name, ingratiates himself with Charlotte by often bringing food for Vivi, even milk, and by being unfailingly gentle and polite. Once he gives her an aspirin, which are impossible to get in Paris, because the infant has a fever. But she is fearful of getting involved, partly because he is, of course, a Nazi, but also because she has seen many women attacked and have their heads shaved for being collabo horizontal. Once her concierge gets wind of the possibility that Charlotte is involved with a Nazi, the concierge "moves her finger at her temple as if she is pulling a trigger. 'Apres les boches,' she hisses, and the words scald like steam."

Among many things, "Paris Never Leaves You" is a novel about identity, and survivor guilt. Not just for Charlotte and Vivi, but for Horace and Herr Doktor Julian as well. One assumes that Charlotte and Vivi are, in fact, Jewish. The book opens in Drancy and they are there. But (spoiler alert), as the reader discovers, this is actually not completely clear, and intentionally so on both Charlotte's part and the author's. "The ornaments were new, but the tree, Charlotte insisted, was a tradition. Her family had always celebrated Christmas. It had taken Hitler, she liked to say, to make her a Jew."

What has become of Vivi's father is equally puzzling.

"How come you never talk about my father?"

"Why don't you ever talk about my father?" Charlotte corrected her. She wasn't stalling for time. At least that wasn't her only motive.

No character in the novel is without enigmas and secrets. All have mysteries and riddles to their identities that are gradually revealed. Charlotte, Horace, Julian the kindly Nazi physician, even Hannah, Horace's wife. The book is like pentimento where as layers are rubbed away, more and more is exposed. The writing is economical, crisp, and often quite brilliant. Ms. Feldman is a master of subtlety, often saying just enough but allowing the reader to marvel at what has been unsaid and yet . . . seen.

"The flames of anti-Semitism, anti-communism, and xenophobia that have always smoldered among the French gendarmerie have been fanned to a bonfire by the occupying forces. Even among those who are not so inclined, fear for their own skin makes them execute Nazi orders." Sound at all familiar? It is hard to read this book in today's political climate without, sadly, seeing once again the rise of Nazism and white supremacy movements in this country and around the world.

Many novels set during World War II are concerned with the horrors of life in the camps. "Paris Never Leaves You" occupies a space I have not encountered before. It is a murky and uneasy and ambiguous space. A place where a Parisian Jew might fall in love with a Nazi, though neither of them is precisely what they seem.

Michael Z. Jody, a regular book reviewer for The Star, is a psychoanalyst and couples counselor with a practice in East Hampton.

Ellen Feldman, whose previous novels include "The Unwitting," lives in East Hampton and New York City.