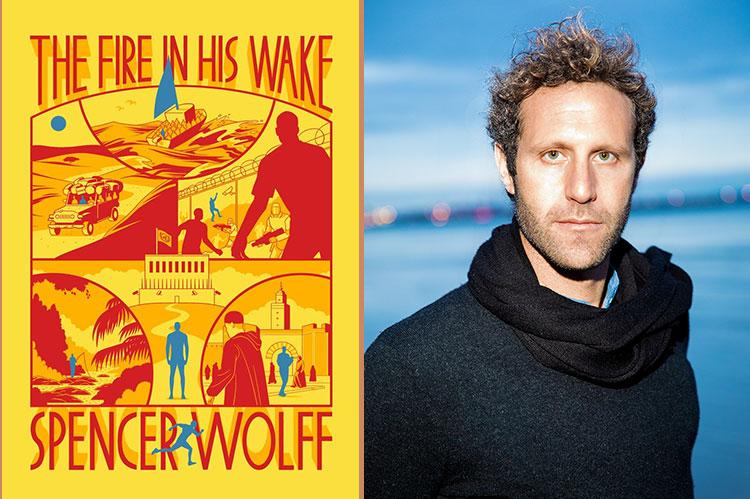

“The Fire in His Wake”

Spencer Wolff

McSweeney's, $28

"The Fire in His Wake," a first novel by Spencer Wolff, will undoubtedly be one of the most ambitious fiction debuts of the year. Epic and remarkably self-assured, Mr. Wolff's book — before it goes horizontal in its final act — is exciting, lucidly written, and genuinely humane.

The story centers mostly on Ares, a young Congolese man from Kinshasa who gets caught between warring factions during the unrest in 1998. Ares's early years are mostly Edenic, his family a close-knit clan that includes his overachieving brother Felix, whom Ares adores, and a father with a locksmith business that affords the family a solid middle-class life. Fleet of foot, Ares competes in track meets, experiences young love, and engages in a teenage rivalry that will figure tragically later on.

These scenes are richly observed, and Ares's life is so quintessentially normal that when violence visits his family it does so with a frankness that is jarring and terrifying. A rival regional faction storms their home armed with machetes and gasoline. The women are raped and slaughtered, and one by one Ares watches his family die before his eyes. The worst, perhaps, is saved for Felix, who has a tire wrapped around his waist and is set afire. Ares watches "the skin shell off his brother's screaming face."

Then there's this passage in which Ares recounts the death of a man and his child who had come to hide at their house: "The last thing I remember was seeing the inside of the man's arm. He was still holding the baby, but it was glowing red bones holding fire that smelled like goat."

The only survivor, Ares manages to flee to a village some miles off. Shell-shocked and destitute, he spends years fishing to support himself. He wrestles with the demons of his past and dreams of fleeing to the north — and ultimately to Europe.

Enter Paul, a local trader, who takes a liking to Ares. Paul is a kind of Falstaffian figure, brandishing bottles of whiskey and a regalia of goggles, animal skins, and crests of feathers. Like Sir John, his dialogue is peppered with aphoristic wisdom. "God only sketched man; it is on Earth that each person makes himself." He is one of those people who seems to know everyone, on both sides of the law, and he promises to help Ares escape to Morocco when the time is right.

By now we have also been introduced to Simon, a young U.N. worker stationed in Rabat. Is Simon a stand-in for the author? They share a similar trajectory that includes an impressive Ivy League pedigree and a stint at the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Simon's idealism soon smacks up against the realities of the crisis in Africa: There are too many refugees and too few slots for resettlement. His beleaguered colleagues fall prey to an ineluctable cynicism.

Simon is well intentioned but has a touch of superficiality in his character; occasionally he bristles at the limitations of Rabat. "He thought of his friends at cushy posts in Brussels or D.C., with their holiday ski weekends and gold-ticket galas. At times he longed for the pleasant affirmations of frilly cocktail dresses and aperitifs on fancy rooftops."

These concerns are juxtaposed against Ares and his Homeric journey north to Morocco. And it's here where Mr. Wolff's storytelling really soars. There are nerve-racking checkpoint interrogations and bursts of sudden violence ("The Fire in His Wake" will not be on the shelves of the Cameroon tourist office anytime soon, I would bet, the country portrayed here as a land of gun-toting lawlessness). More than once Ares's foot speed is all that separates him from death. Even Morocco is barely a respite. In Fez, he works as a day laborer at a construction site, but on payday is run off empty-handed with a wrecking bar.

Eventually, of course, Ares's and Simon's paths will cross in Rabat.

These days, in a novel concerning African refugees and European gatekeepers, you steel yourself for homilies about racism and white privilege. Thankfully, Mr. Wolff's novel is a more nuanced affair. The racism here is portrayed as a universal scourge rather than a uniquely Western problem. The regional wars of the Congo, for example, are reported as manifestations of a brutal xenophobia.

In Morocco the lighter-skinned North Africans condescend to the darker-skinned Congolese. Witness Ares on a walk through Rabat: "Within minutes, a posse of local children had latched on to them. They hooted out monkey calls and clambered on all fours." In another scene, when Ares visits a brothel where a man sells his own daughters for sex, you get ready for the part where his conscience gets the best of him and he leaves before the deed is done. In this novel, that doesn't happen.

And though Mr. Wolff portrays many of the mostly white case workers at the UNHCR as callous, he is sympathetic to their plight. Beleaguered and overworked, they see the applications for resettlement pile up on their desks by the thousands. Some refugees lie or exaggerate their stories to gain advantage, and case workers become inured to the endless stories of torture and genocide. Cynicism becomes a natural defense mechanism.

There is not a page of "The Fire in His Wake" that is not skillfully written and compelling, and yet the novel feels slow on the back end. As Ares runs into an intractable U.N. bureaucracy, so does the novel seem to run into a wall. We are hit with a motherlode of deadening acronyms — F-O, PALS, RSD, EO, RRF (these in just a two-page stretch). Simon's romance with a woman named Nadia feels obligatory. An elaborate riot scene is tacked on as a climax, but lacks the heat of the novel's other action sequences.

Nevertheless, "The Fire in His Wake" is an utterly successful first novel, one that sports a flair for harrowing adventure matched with a complex political conscience. It is not too early to say Mr. Wolff's novel will be one of the best debuts of the year.

Kurt Wenzel is a novelist and book critic who lives in Springs.

Spencer Wolff is a journalist, documentary filmmaker, and past photographer for The Star. He lives part time in East Hampton Village.