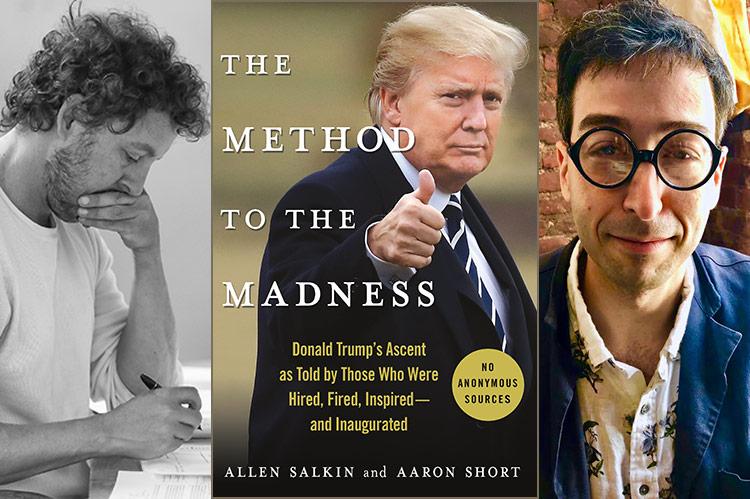

“The Method to the Madness”

Allen Salkin and Aaron Short

All Points Books, $28.99

The reviewer begged to differ: “More important, one might suggest, was Mr. Trump’s weaponization of celebrity, the stagecraft, screencraft, and marketing magic he mastered through his reality TV show, ‘The Apprentice,’ and the sense he developed of a polarized, disgruntled America that would become his base, its values, desires, and prejudices to which he so successfully plays.”

Said reviewer (full disclosure: me) is therefore pleased that yet another recent volume fleshes out exactly that hypothesis of The Donald’s unlikely but, as it recounts in detail, far from accidental path to the presidency. It is “The Method to the Madness: Donald Trump’s Ascent as Told by Those Who Were Hired, Fired, Inspired — and Inaugurated.”

Through snippets of their interviews with more than 100 men and women — all identified — who worked for or with or covered Mr. Trump going back decades, the veteran New York journalists Allen Salkin and Aaron Short trace his increasing interest in, and preparation for, elective office, even as mainstream media and veteran pols dismissed him as a brazen, buffoonish billionaire interested only in teasing and buffing his name and brand.

Many of the familiar sources are here: the political operators Roger Stone and Steve Bannon, the media pundits Glenn Beck, Pat Buchanan, and Tucker Carlson. But we also hear from such as Jeff Jorgensen, chairman of Iowa’s Pottawattamie County Republican Central Committee and founder of the Republicans for Conservative Values PAC, as well as Russell Verney, former Ross Perot presidential campaign director, and Marji Ross, president of conservative Regnery Publishing, all of whom played parts in Mr. Trump’s progress.

It is a long and winding road that the authors pick up in the fall of 1987. Intriguingly, given continuing controversy, just two months after Trump visited Moscow to discuss building hotels, he spent nearly $100,000 on a full-page open letter in The New York Times that was likely to warm the Kremlin’s heart. Calling for “a little backbone” in U.S. defense policy, it also demanded that America “should stop paying to defend countries that can afford to defend themselves.” Allies like Japan, for example.

Mr. Trump, the authors note, “is not known for spending money without hope of receiving something tangible in return,” but they resist speculation on what, if anything, the Russians might have had in store for — or on — him, the question that still lingers.

“Whatever his motivation,” it led to an appearance on CNN’s “Larry King Live” in which Mr. Trump talked trade policy, touted an impending address to a New Hampshire Republican luncheon, and parried any presidential speculation.

Mr. King: “You realize now, in just setting foot in that state, people are going to presume things.”

Mr. Trump: “Well they can presume whatever they want. I have no intention of running for president, but I’d like a point to get across that we have a great country, but it’s not going to be great for long, if we’re going to continue to lose $200 billion a year.”

In New Hampshire, a week before publication of “The Art of the Deal,” his first mega-seller, Mr. Trump delivered “a stem-winder” about trade deficits, taxes, and his business skills to an audience of 500 that Mr. Stone had arranged. “I’m tired of nice people already in Washington. I want someone who is tough and knows how to negotiate,” he shouted.

“Roy was the first one to spot the potential for Donald Trump . . . tall and handsome and audacious,” says Mr. Stone, who came to see Mr. Trump as a “genius showman when it comes to getting press and getting focus on your idea.”

Some local pols, like Manhattan Borough President Andrew Stein and New Jersey Congressman Robert Torricelli, thought Mr. Trump was a moderate Democrat or Independent, but he also donated regularly to Republican leaders while disdaining them all as a burden of doing business. “Donald didn’t like any of them,” says Barbara Res, a former Trump Organization construction manager. “He just wanted influence, that’s all. . . . He doesn’t feel any way about an issue. What can it do for him? How can he make it work for him?”

By 1992, another businessman who disdained traditional politicians, their economic and trade policies, was shaking up the presidential race. Ross Perot ultimately won 19 percent of the vote and went on to form the Reform Party, which the celebrity wrestler Jesse Ventura rode to the governorship of Minnesota.

Along with the Green Party formed by Ralph Nader, the new outsider activism attracted the interest of Mr. Stone and Mr. Trump. “I saw very early on that he had the capacity to be elected president. I didn’t really care what party,” says Mr. Stone. “I was just looking for that opportunity. I recognized that the voters would have to reach their saturation point with conventional politics and parties, but I thought that moment was coming. And it ultimately came.”

“Roger told him, ‘Hey, you don’t have to do anything, really, just get your name out there, it’ll be fun. You’ll be more famous,’ ” recalls Rick Wilson, a G.O.P. political strategist. With an eye on the Reform Party’s coming choice of a 2000 presidential candidate, Mr. Stone in 1999 commissioned a Trump issue book — “The America We Deserve” — by a Virginia-based ghostwriter, Dave Shiflett of the G.O.P.-connected White House Writers Group. “At the time he was nothing but a real estate guy, a Manhattan jet-setter. . . . This would be my first published work of fiction,” Mr. Shiflett thought.

There was a meeting in Mr. Trump’s office, “an hour and 45 minutes,” Mr. Shiflett recalls, “all that pink marble . . . surrounded by beautiful women. . . . He was most animated about terrorism . . . talked about North Korea and how they must never be allowed to get a nuclear weapon . . . also talked about Iran . . . very much for single-payer health insurance . . . very pro-gay rights.”

The brain trust clarified and specified. “We were running more as a centrist for the Reform Party nomination, hoping to have a candidate to our right and candidate to our left . . . more centrist on health insurance, on abortion,” says Mr. Stone. Then there was a tip to Newsweek, picked up by The New York Post and Daily News, that Trump was thinking about grabbing the Reform banner. If nominated, “I would probably run and probably win,” he confirmed.

“Is this a joke? I have never once heard his name mentioned in the Reform Party,” said its chairman, Russell Verney. But he soon would, as the party’s front-runner, Pat Buchanan, was forced to defend himself on network TV against Mr. Trump’s charge he was a “Hitler lover.”

Without formally entering the Reform race, Mr. Trump continued making media waves. “I really believe the Republicans are just too crazy right . . . just nuts,” he told Tim Russert on NBC. “And I’m seeing the Democrats as . . . I mean Bradley and Gore . . . just too liberal for me.”

He was also making getting-to-know-you/know-me appearances, some (at $100,000 per) as part of a seminar series run by the motivational guru Tony Robbins. Many saw him as an opportunist, but in St. Paul he spent two or three hours questioning Governor Ventura’s campaign chairman, Dean Barkley, who recalls: “Stone was doing a lot of note-taking. Basically Trump asked a lot of things. What was your strategy? What did you try to do? How did you think he could win without spending a lot of money?”

In the end, Mr. Salkin and Mr. Short report, Mr. Trump calculated that the cost was too high and that the chances of forcing all other Reform candidates to withdraw was too low. Never launching a formal organizing effort further fostered his reputation as a political tease. But he’d gotten closer to the kind of angry, anti-traditional, pre-Tea Party outsiders who would shortly become his audience, when “The Apprentice” began in 2004, and later his constituency.

And with the “exaggerated character strengths, and extracted distillates of drama from hours of raw footage” as masterminded by Mark Burnett, the British-born creator of “The Apprentice,” Mr. Trump’s persona grew “exponentially more powerful,” the authors say. “Television remade Trump into an avuncular commanding character with a catchphrase [‘You’re fired!’] that caught on in every corner of the country.”

“The medium also taught Trump new skills that would translate to politics and the White House,” they argue, “such as staging” — the escalator entrance for his presidential announcement — “cliff-hangers (who will be fired next), and the potential kindness of outdoor lighting (Rose Garden videos).”

But Mr. Trump brought insight of his own. “Mark went to Trump’s office and pitched him the idea [of Trump as judge and executioner] and Trump said ABC had been asking him about doing a reality show with cameras following him around,” according to Conrad Riggs, who worked with Mr. Burnett to develop “Survivor” and “The Apprentice.” Mr. Trump said, “This is better, because it’s not just about me. It’s about the American dream. It’s about giving someone an opportunity.”

On the other hand, the advertising exec and TV personality Donny Deutsch remembers the cruder side of Mr. Trump at that point. “Walking down the halls of my agency, Trump would go, ‘Oh, that’s a piece of __.’ He just always talked about women. . . . You could not get into a 30-second conversation where he wouldn’t take it to something, ‘That girl’s beautiful.’ He was that guy.”

Mr. Trump himself all but reveled in that presumable drawback to a presidential candidacy. In 1998, for example, to Chris Matthews on CNBC he tantalized: “Can you imagine how controversial I’d be? You’re thinking about [Clinton] with the women? How about me with the women?”

The book also replays some inside accounts of Mr. Trump on race during “The Apprentice.” Bill Pruitt, a TV veteran and producer of “The Apprentice” seasons one and two, recalls him asking about a potential black winner of one contest: “But will America buy a __ winning?”

Mr. Pruitt would not repeat — but did confirm — Mr. Trump’s use of the N-word, say the authors. In a 2018 Vanity Fair story, the Trump lawyer Michael Cohen recalled him saying of that episode: “There’s no way I can let this black fag win!”

“The truth is we told stories that involved Donald Trump,” Mr. Pruitt explains. “Were they a con? I don’t know. A con would imply malice or forethought. . . . It was a fabrication about a millionaire, a made-up story with realistic intonations. I use those terms in a very pointed way to get people closer to thinking that maybe storytellers and myself helped shape their views on this person. . . . We all need to understand at the end of the day what’s happening to our minds when we’re being told a story.”

Next week: Donald Trump gets more political.

Allen Salkin summers in Amagansett.

David M. Alpern, a former Newsweek senior editor, ran the “Newsweek On Air” and “For Your Ears Only” syndicated radio shows for over 30 years and now moderates discussions on foreign affairs for the library in Sag Harbor, where he lives.