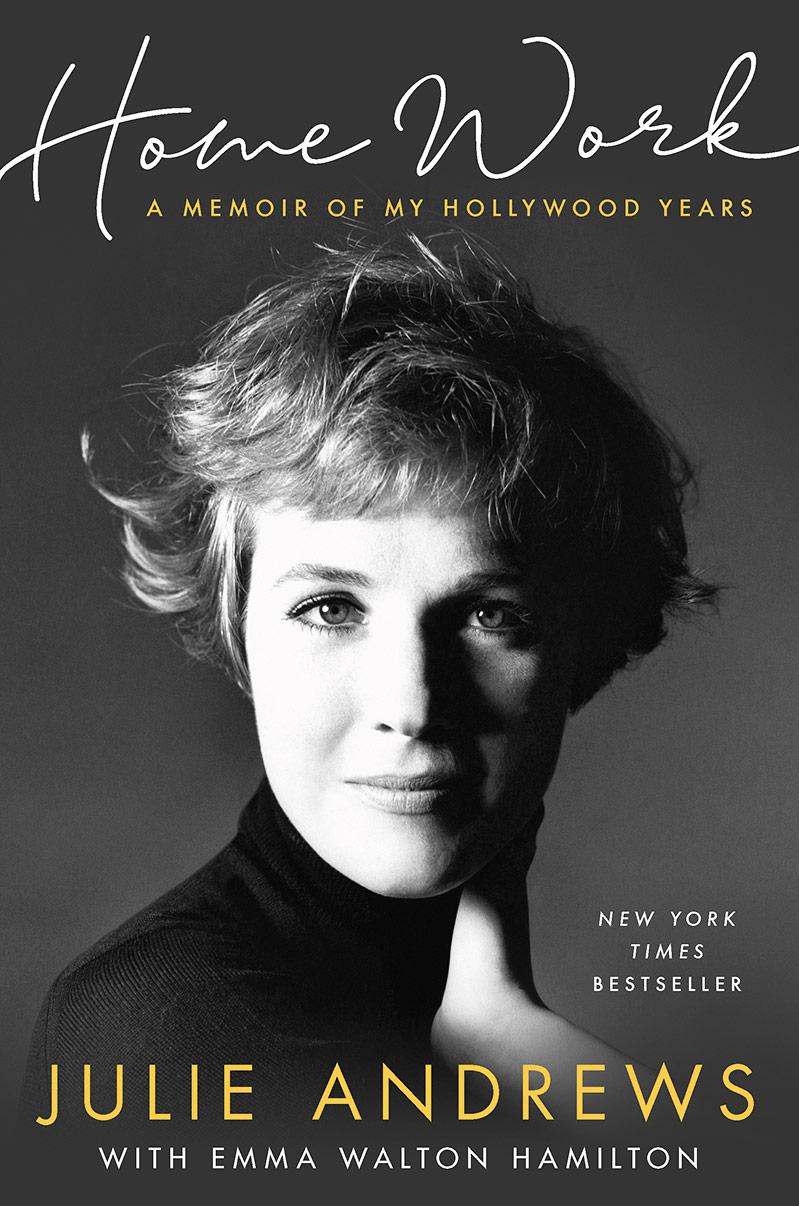

“Home Work”

Julie Andrews

With Emma Walton Hamilton

Hachette Books, $30

Late in this revealing memoir of her Hollywood years, “Home Work,” the international singer, actress, and Hamptons icon Julie Andrews recalls filming a scene in “The Man Who Loved Women,” a 1983 adaptation of the Francois Truffaut classic written and directed by her husband, the comic genius but frequent depressive Blake Edwards. In it, Edwards’s own psychoanalyst, through a concealed earpiece Ms. Andrews wore, suggested proper responses that she, as a shrink in the film, should make to lines improvised by Burt Reynolds as the serial skirt-chaser of the title.

“I had the peculiar sensation of art imitating life, and it felt more than a little bizarre,” Ms. Andrews writes.

But surprisingly often it is life that imitates art — or at least echoes it — in this delightfully detailed, dramatic account, a continuation of Ms. Andrews’s earlier tale of life onstage, “Home.”

Of course her role in the 1968 movie “Star!” as the legendary singer and actress Gertrude Lawrence — an English child prodigy of an earlier era — benefits from Ms. Andrews’s own experience in English concert halls and vaudeville theaters (mostly “rather shabby”) even before her teens.

At age 11 she performed for the troops — and the Queen — at London’s Stage Door Canteen (“You sang beautifully tonight,” said Her Majesty), and two years later for King George VI at the Palladium. You can still hear that for yourself on YouTube.

In fact, many of her songs and shows can be enjoyed in whole or in part that way, even her embodiment of Eliza Doolittle in “My Fair Lady” on Broadway (Audrey Hepburn got the movie, on which more later). Ms. Andrews was sad that her portrayal would be unknown to later generations. But not so thanks to video of scenes reproduced on old TV shows.

Eliza also echoes in Ms. Andrews’s life, albeit in reverse. Surrey-born Julie actually had to learn to speak Cockney for “My Fair Lady” on Broadway. And like Eliza (at least early on), Ms. Andrews is ever doubtful of her ability to meet challenges professional and personal.

After her first film, Disney’s G-rated “Mary Poppins,” for example, she agreed to do “The Americanization of Emily” and fall in love (on screen) with James Garner as a World War II general’s aide proficient in procuring “anything . . . from booze to cigarettes to pretty ladies.”

“I felt that I was a rather odd choice for Emily,” Ms. Andrews writes. “While I was very nervous . . . I recognized that it would be a wonderful contrast [to ‘Poppins’], and perhaps help me to not be typecast . . . if I were later . . . another nanny” — in “The Sound of Music,” already in the wind.

“Once again I felt I understood from the script what was required of the character, yet I lacked the acting skills to put it into practice,” she continues. “It’s a horrible feeling to know that you understand a role, but don’t know how to get there. . . . As with my first days on ‘Poppins,’ I simply opened my mouth and said the words as best I could. Happily, Paddy’s [Chayefsky] brilliant dialogue did a lot of the heavy lifting for me.”

There’s also more than a trace of the Poppins magic in Ms. Andrews’s endless negotiation — and globe-girdling navigation — between the demands of her blossoming career and private life as supporter and caretaker for an ever-growing contingent of parents, stepparents, spouses, various other relatives, all their assorted accidents, ailments, anxieties — and a carload of kids.

First came Emma (with whom, as an adult, she wrote this volume), her daughter by her childhood sweetheart and first husband, Tony Walton, the English set and costume designer. Then there were the children of her second husband, Edwards, two adopted daughters from Vietnam (she also went to witness the plight of that war’s orphans firsthand), plus an ever-morphing menagerie of dogs, cats, and birds — in homes that took her back and forth from London to New York to Beverly Hills, Malibu, and Gstaad in Switzerland.

Exhausting just to read about, and not without psychic cost, as she learned in analysis. “I began to understand that the stress of trying to keep my family together all those years — supporting them at such a young age; my mother’s depression; my stepfather’s alcoholism . . . followed by the steep learning curve and vigorous demands of Broadway, a marriage and a child, and now Hollywood . . . all this had generated powerful emotions . . . which I had buried in order to survive.”

Still, it was for Edwards’s daughter Jennifer that she started writing her first children’s book, “Mandy,” followed over the years by more than 30 others, most in collaboration with the grown-up Emma.

But the most striking echoes of her art in her own life may well come from the role as Maria von Trapp, also a family caretaker, of course, but thanks to Rodgers and Hammerstein also a full-throated lover of life and all its natural pleasures. Drawing on extensive diaries, Ms. Andrews fills her account with happy memories of favorite things — sights and sounds and scents that thrilled her, mountains, flowers, seas, and skies.

To build stamina for impending performances in Las Vegas at one point, she would vocalize on long walks around her chalet in the Gstaad countryside — so the hills were, indeed, alive with the sound of music!

And it was that title song she was “singing flat out . . . when suddenly a group of Japanese tourists . . . crested the hill in front of me. They recognized me, and looked simply stunned. I dashed for home, mortified.”

At least there was no helicopter overhead like the one whose downdraft so irritated Ms. Andrews by repeatedly knocking her into the mud and grass while filming that classic opening scene.

Far surpassing Eliza at the ball in “Fair Lady,” she met and often worked with a who’s who of Hollywood, from (alphabetically) James Aubrey, with whom Edwards clashed when Aubrey took over MGM (and whom Edwards unknowingly came close to killing in a roadway near-miss), to Richard Burton, Michael Cain, and Noel Coward. And ending with such as Peter Sellers (Blake’s “Pink Panther” star), Elizabeth Taylor, Dick Van Dyke, Max von Sydow, Peggy Wood, and Ed Wynn.

But Ms. Andrews says neither she nor Blake (he called her “Jools”) “was much interested in the Hollywood social scene. Our idea of a good evening was having a quiet supper at home with a few friends, or taking the kids to one of their favorite local restaurants.”

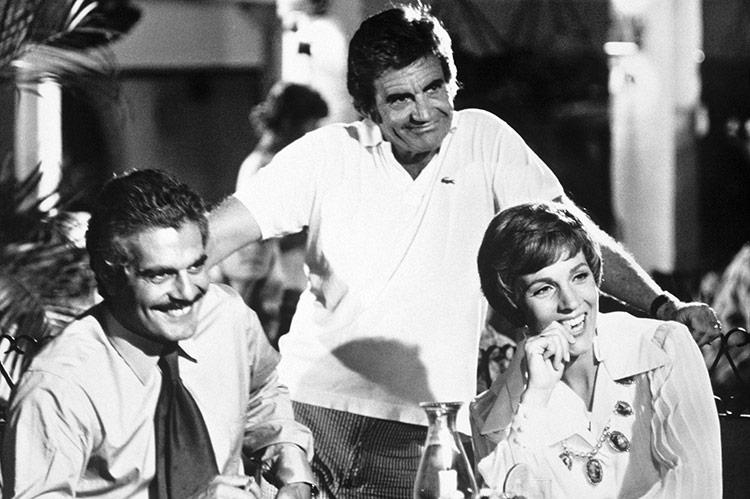

Edwards began his courtship by honking at her from his Rolls-Royce several times when each was idling at a stop sign near their respective psychoanalysts’ offices. Soon he was offering her a role in his upcoming “Darling Lili,” a World War I spy film, then inviting her to a screening of “What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?” and finally taking her to dinner, where they discovered both were separated from first spouses and available.

A drive along the Pacific Coast Highway was “unbelievably romantic,” Ms. Andrews writes. “Blake eventually pulled onto the Malibu Bluffs and parked the car. We gazed out at the full moon hanging over the sea, and he quietly took my hand.”

“If he doesn’t kiss me, I am going to go crazy,” she thought. “Then he did just that.”

Next comes one of the delightfully naughty bits in this book. Blake takes Julie to see his new house, and she offers him one of three new lilac trees she has just bought for hers. “Oh, you know, don’t you?” he demands. “Know what?” she asks.

It turns out that before they met, Blake had been at party where the big question was whether Julie had received the Oscar for “Mary Poppins” because of talent or as consolation for losing the Eliza role.

“I know why she won. She has lilacs for pubic hair,” Blake confesses he said. “I’m so sorry.”

“That’s all right,” she smiles. “But — how did you know?” After which “lilacs were a theme at every birthday and anniversary.”

A footnote: At the Oscar ceremony that year, Hepburn (not nominated) confided: “Julie, you really should have done ‘My Fair Lady’ . . . but I didn’t have the guts to turn it down.” Ms. Andrews said she understood completely “and . . . we became good friends.”

Sadly, Blake’s comic genius and sensitivity were increasingly overcome by bouts of depression, even approaching suicide, which created predictable strains. He was later one of the celebrities describing the torment of chronic fatigue syndrome in the documentary “I Remember Me.”

But “despite the dramas, the transgressions, the ups and downs of our marriage, I still loved him deeply,” Ms. Andrews writes. “We remained married for another twenty-five years before he passed away at the ripe age of eighty-eight.”

Not mentioned is the loss of her singing voice — after hoarseness forced her from “Victor/Victoria” on Broadway, then led to botched surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and finally a malpractice case ultimately settled for an undisclosed amount.

It was yet another case of life echoing art. In Edwards’s semi-autobiographical “That’s Life,” shot at their actual Malibu home and their last film together, Ms. Andrews is a singer awaiting results of a biopsy on her vocal cords. “Feeling oddly superstitious about playing a character facing the loss of her voice,” she recalls, “I asked my analyst if investing emotionally in the role could put me at risk of some psychosomatic manifestation. He assured me I had nothing to worry about.”

Perhaps there is the slightest of acknowledgement of this sad silencing as Ms. Andrews sums up. Now a Dame of the British Empire with an Oscar, a BAFTA (from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts), five Golden Globes, three Grammys, two Emmys, the Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, the Kennedy Center Honors Award, and the Disney Legends Award, she says:

“I have been lucky. To be given the gift of song — and to recognize that it was a gift [her emphasis]; to have been mentored by giants, who taught, influenced, and shaped me; to have gained resilience from hard work; to have loved, and been loved; and to have sometimes felt an angel on my shoulder, a reassuring presence that helped center and guide me when I needed it most . . . actually, that’s more than luck. I am profoundly blessed.”

Julie Andrews lives in Sag Harbor, where Bay Street Theater was co-founded by her daughter and co-author, Emma Walton Hamilton, now an instructor in the M.F.A. program at Stony Brook Southampton.

David M. Alpern, a former Newsweek senior editor, ran the “Newsweek On Air” and “For Your Ears Only” syndicated radio shows for more than 30 years. He lives in Sag Harbor, where he moderates discussions on foreign affairs for the John Jermain Memorial Library.