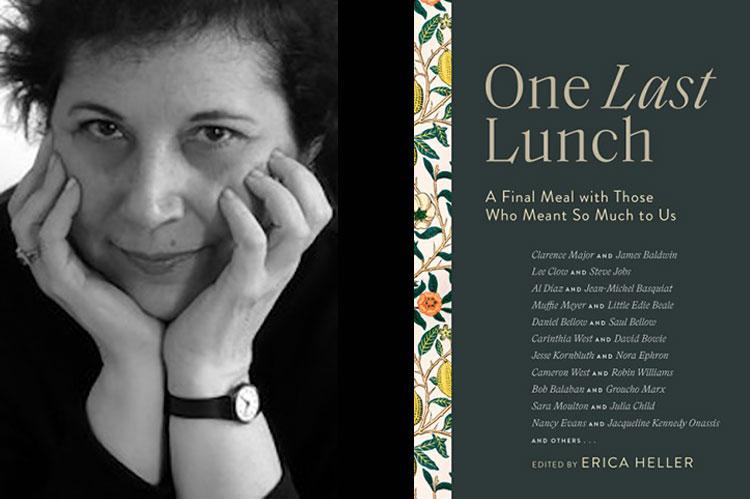

“One Last Lunch”

Edited by Erica Heller

Abrams Press, $25

Mortality and food are strange bedfellows. Of course, there was the Last Supper, but carp or carpe diem is not something you're likely to indulge in the afterlife.

The publishing lunch, a once-venerable institution, is currently in remission and due to the pandemic possibly on its way to a premature death. Indeed, Erica Heller's "One Last Lunch" is an example of those old-fashioned concept books with titles like "My First Affair" hashed out over lunch at one of those restaurants like the old Union Square Cafe, where in the lead essay the author/editor is reunited with her father, Joseph. The two are greeted "personally" by the almost equally legendary restaurateur Danny Meyer and served "great quantities of oysters, pasta, and fish" within eyeshot of old friends like Carl Bernstein.

Ms. Heller's colorful compendium of essays is a moveable feast, giving a number of writers the chance to share a repast with their deceased friends, lovers, colleagues, and occasional alter egos.

Saul Bellow's son Daniel has one last meal with his famous father, now married to Mary McCarthy, who herself was once sued for a quip she made about Lillian Hellman, "Every word she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the.' "

Bellow begins the reunion by saying, "Don't shit me to spare my feelings, Daniel. I'm dead." The crusty repartee sounds a little like the beginning of "Augie March": "I am an American, Chicago born . . . and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style. . . ."

The Bellows meet at Barney Greengrass, where Philip Roth is the waiter. Anyone who ever got a glimpse of Roth at a literary event might realize how spot-on the characterization of him is. The author of "Portnoy's Complaint" could easily have been mistaken for a harried deli waiter.

But in all his excitement about meeting up with the dead father, Daniel misses the point. If you're talking about Barney Greengrass, you have to deal with the Chopped Liver Wars of the 1990s. Then, the journalist Ron Rosenbaum fenced off with the food critic Gael Greene about the virtues of Barney Greengrass's chopped liver over that of Zabar's, the Stage, the Carnegie, the Second Avenue, and Katz's, in an internecine conflict as vituperative as that between the rival literary journals Lingua Franca and Social Text in 1996.

Brook Ashley takes her godmother, Tallulah Bankhead, to Sardi's, and Bob Balaban envisions a meal with Groucho Marx at the now-defunct Lindy's, once famous for its cheesecake and "insulting waiters." Bankhead orders Jumbo Shrimp Sardi in Garlic Sauce and Profiteroles au Chocolate.

No discussion of either the dead or the ghosts of famous literary figures would be complete without Chinese food. Benjamin and John Cheever, who haven't seen each other since 1982, repair to the old China Bowl at 152-4 West 44th, with its "acres of white tablecloth" and "heavy napkins," right around the corner from the old New Yorker at 25 West 43rd Street. There they order such iconic dishes as wonton soup, egg rolls, barbecued spare ribs, and lobster Cantonese.

Obviously, the writers of these imaginings express a good deal of love and admiration for friends and relatives, which the reader might not share. How does one criticize a vignette that is essentially a kind of obituary? It's like saying you don't like someone's life. Yet everyone has their stories.

I once saw Joseph Heller on the elliptical at the Omni gym in Southampton. When I got the courage to go over to tell him how much I liked "Something Happened," he rudely sloughed me off. Yet that was back in the day when artists and writers were given license to hurt others as well as themselves. I eventually learned that I could love Bergman, but not necessarily like him. The last words Ben Cheever puts into his father's mouth before they part are "We should do this again soon. I really missed the lobster Cantonese."

Still, there are some endearing apparitions in this book of the dead. Phyllis Raphael is touchingly reassured by her grandson Max, who died of a brain tumor when he was only 7, and tells her, "I don't want you to worry. It's all cool." Leonard Cohen speaks thusly about heaven to his godson David Layton (who obviously knows his subject), "much like everywhere else. People are still searching for something, even after there is nothing to search for."

Allen Ginsberg symbolically or not eats or bites his tongue. Oliver Sacks, who is quoted as saying, "When you die, that's it. The lights shut off, and there is no more," lives up to his words by failing to show up for his last lunch with his cousin Adrien Lesser at Russ & Daughters. Maureen Stapleton begins her lunch with her son, Dan Allentuck, by announcing one of her favorite admonitions, "Anything we don't eat, we doggy-bag!" And Rick Moody remarks wistfully about his deceased sister: "I have waited now twenty-two years for my sister to come back, other than fleetingly in dreams, to talk again in the easy way of the old times, with her rapturous laughter, and her bounteous care and concern for her parents, siblings, and children."

The fact is that these last lunches are more about the writers who envision them than the subjects. Kaylie Jones brings a Chateau Margaux 1921 to her lunch with her father, warning, "I quit drinking. Twenty-six years ago. Booze almost killed me. Just like it's eventually going to kill you. I'm older now than you'll ever be."

In this sense while they can present scabrous portraits, like that of the novelist Caroline Leavitt, who painfully knocks on the same door to find her father as unforthcoming in death as he was in life, they often involve some degree of wish fulfillment. Hope springs eternal in Elizabeth Mailer's reliving of the night of Nov. 20, 1960, when her father famously stabbed her mother with a pen knife. In this version, taken from her mother's putative diary, the cocktail party where the incident took place is canceled, and Norman takes the family out for a spin to the Palisades in a Chevy, with everyone going peacefully to bed and he and his wife, Adele, cuddling on the couch the next morning.

Erica Heller bookends her initial outing with yet another lunch and host of what turn out to be unfulfilled wishes that lie like condiments on the table. To a hypercritical and dismissive father whom she describes as "a skilled and almost effortless voice of my very own apocalypse," she accords a last chance. They meet in the new Union Square Cafe on 19th Street. As is his custom, he's started to eat before she even arrives. She gets up the courage to ask, "Have you ever loved me?"

"You know I don't have discussions like that. If you asked me here to argue. . . ." Ms. Heller doesn't get what she was after, even in a fantasy. "Without question, ours has not been the happy or healing lunch I'd so longed for, the informative, loving, sentimental, long overdue rapprochement," she concludes. "But realistically, it's the only lunch the two of us could ever have."

Francis Levy is a Wainscott resident and the author of the comic novels "Erotomania: A Romance," "Seven Days in Rio," and "Tombstone: Not a Western." He blogs at TheScreamingPope.com.

Erica Heller is the author of "Yossarian Slept Here," a memoir. She has spent many summers in East Hampton, where her father, Joseph Heller, lived.